A protest meeting against removals, eNanda, KwaZulu-Natal, 1982. (Omar Badsha)

This moment’s gaping generational divide, exacerbated by the Covid-19 pandemic, with its accompanying sense of history being lost and collective memory fading, comes into sharp focus when speaking to social documentary photographer and artist, Omar Badsha.

The 75-year-old Badsha is a political and cultural elder. A colossus.

He has lived and made history as a political activist and trade unionist in KwaZulu-Natal, especially from the 1970s Durban Moment onwards. Badsha has also documented and archived history through his photography, the co-founding of the non-racial Afrapix photographers’ collective in the early 1980s and, for the past two decades, as chief executive of the South African History Online (Saho) website.

During a pandemic that threatens an entire generation of elders, or seeks to cloister them from our everyday imagination, it is a relief to hear his voice. Likewise, in his words, to be reassured by the familiar sense of Badsha’s effervescent activist spirit; one that embraces struggles that are continuously being fought and powers passionately challenged.

But the news is not good: “We are on the verge of closing down, broer,” Badsha says of Saho over the phone from his home in Cape Town. The pandemic has hit hard. Funding has dried up and Saho, which needs R3.5-million a year to survive, has hobbled through much of 2020 with the assistance of volunteers. It can’t for much longer.

Badsha says money from the Lottery Board, which is beset by scandalous allegations of misspending, has dried up and he has been unable to clarify with the department of sports, arts and culture what has happened to the second of three proposed annual R1.5-million funding tranches.

The department’s Zimasa Velaphi said that although that money had initially been available to Saho on the completion of various report-backs from the online heritage website, it had since been reprioritised for Covid-relief funding.

Funeral of Sthembiso Nzuza and Moses Ramatlotlo, members of MK killed in an armed clash with police, KwaMashu, KwaZulu-Natal, 1984. (Omar Badsha)

Funeral of Sthembiso Nzuza and Moses Ramatlotlo, members of MK killed in an armed clash with police, KwaMashu, KwaZulu-Natal, 1984. (Omar Badsha)

“Our other funders have cut back on funding. Some money has been moved to Covid-19 relief work, which is understandable, but the state really hasn’t come to the party to support us or other institutions like us,” Badsha says.

The Covid-19 pandemic has exacerbated an already precarious funding landscape in which organisations like the National Institute for the Humanities and Social Sciences have experienced budget cuts and university history departments, regular Saho partners, have experienced shrinkages in student numbers and university budgets.

The organisation’s training programme, which draws in history and information technology students from FET colleges and the four Western Cape universities and is supported by the sector education and training authorities, “has really come to the rescue this year”, says Badsha.

Without the internships, the various histories that Saho unearths — alternatives to white hegemony or post-apartheid reductivism — would have ground to a halt.

With students working remotely, and joined by bands of volunteers, the research into projects like the “history of the liberation struggle”, “women histories and liberation movements” and the “history of places” continued, but not with the same momentum of previous years, because of various challenges, including the cost of data.

Yet, Badsha is adamant that Saho’s mission to rewrite history by “reinserting the roles of women, workers and Black people” survives because it is essential to addressing almost four centuries of colonialism, apartheid and the attendant trauma inflicted on ordinary people.

PRETORIA SOUTH AFRICA – MAY 09, 2018: South African Photographer, Historian and Activist Omar Badsha during the launch for his photographic book, Seedtimes at the University of Pretoria on May 09, 2018 in Pretoria, South Africa. Badsha is an award winning artist, documentary photographer, and former trade unionist, initiator of Afrapix and founder and head of South Africa History online. Seedtimes is his sixth and latest book. In this month he was honoured with the order of Ikhamanga (silver) for his contributions. (Photo by Gallo Images / Alet Pretorius)

PRETORIA SOUTH AFRICA – MAY 09, 2018: South African Photographer, Historian and Activist Omar Badsha during the launch for his photographic book, Seedtimes at the University of Pretoria on May 09, 2018 in Pretoria, South Africa. Badsha is an award winning artist, documentary photographer, and former trade unionist, initiator of Afrapix and founder and head of South Africa History online. Seedtimes is his sixth and latest book. In this month he was honoured with the order of Ikhamanga (silver) for his contributions. (Photo by Gallo Images / Alet Pretorius)

“One of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s [TRC’s] recommendations was that history be retold. There are over 30 000 people mentioned in the TRC: Where are their stories? It is essential for this generation and the next, to know who these people were and what they did,” he says.

Badsha continues: “I remember both [anti-apartheid icons] Govan Mbeki and Phyllis Naidoo being aware of the problem of not writing our own histories. They asked me often who would write our histories, if we didn’t. Govan Mbeki was especially insistent.”

Having been awarded the Order of Ikhamanga in Silver by President Cyril Ramaphosa for his life’s work, Badsha had written to the presidency in June, asking that Saho be adopted as a special project of his office until it becomes self-sufficient in two years’ time.

After a Mail & Guardian inquiry last week, the presidency wrote to Badsha to acknowledge receipt of the letter and to inform him that the matter had been referred to the department of sports, arts and culture.

Over the past 20 years Saho has extended its research programmes to include South African historical timelines and produced profiles and features of artists like Dumile Feni, as well as lesser known but no less significant political activists like Paul David, who died recently, and various other organisations and people of which little is documented. It had also started assisting anti-apartheid activists to write their memoirs and have their manuscripts publish as part of Saho’s “Lives of Courage” book series.

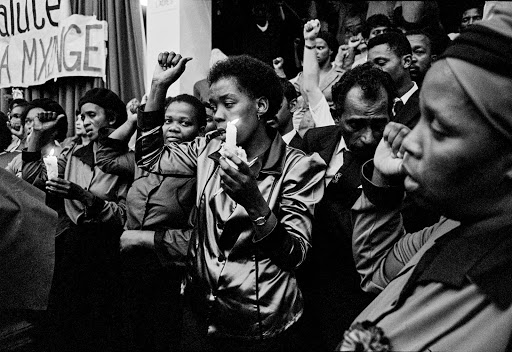

Memorial service for Victoria Mxenge, University of Natal, 1986. (Omar Badsha)

Memorial service for Victoria Mxenge, University of Natal, 1986. (Omar Badsha)

It has set up the Online Classroom which is the foundation of its schools’ history project which makes available for download the entire history curriculum from grades 4 to 12. Together with the department of basic education, it also runs the annual Nkosi Albert Luthuli Oral History Competition.

But the project is interventionist too. It has responded to history in the making, as was the case with the Fees Must Fall movement, which dominated university campuses for several years after flaring up in 2015.

“I went to UCT [University of Cape Town] when Fees Must Fall started and there were 20 to 30 students who had occupied the administration block,” Badsha says.

“They said they wanted to know more about what UCT students did in 1968 and so on. We discussed this history and I invited them to Saho to develop Fees Must Fall timelines, upload documents, videos and interviews so that we have this archive for the next generation.”

Badsha says he is worried that a major project, to gather information about the South African Communist Party in time for its centenary next year, may flounder because of the lack of funding.

Saho has developed over a period during which the internet, and the society connected to it, appears increasingly ahistorical, even anti-historical, at times.

Yet, contrary to the notion that history is being undermined by technology, Badsha sees new shoots of optimism and struggle on the web, which he considers “the newspaper of the world” and where there is a continuous need to build an archive.

He is also buoyed by the emergence of “democratised and hyper-local recording of histories”, which he sees developing on social media.

“A lot of new history on social media is centred on personal nostalgia: it’s about families, cinemas and cafes, the ordinary places and spaces that ordinary people lived their lives in. This is significant because it gives people the power to tell their stories,” he says.

Milan Kundera’s observation that the struggle against power is the struggle of memory against forgetting may be trite, but it seems ever more relevant in an interregnum slowly forming against the backdrop of a global epidemic. If this generation is to respond to its calling, rather than betray it, history, and organisations like Saho, appear essential.