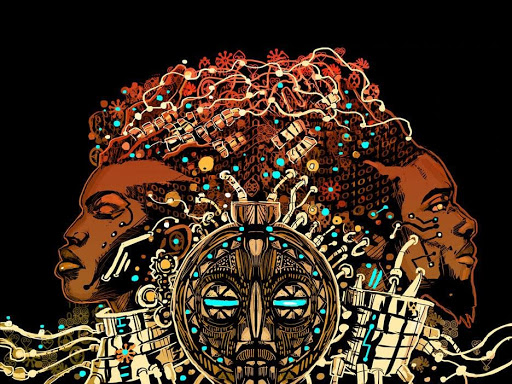

Black woman’s ecstasy (Kimberly Marie Ashby)

The global pandemic, as an apocalyptic event itself or as a catalyst towards the apocalypse — one whose climate, economic and social outcomes disproportionately affect Black and Brown people — has accelerated and deepened our considerations of world endings.

We find ourselves thinking about life in an age of dying; of a persistently lingering past reimagining itself in different versions of oppression and injustices.

We find ourselves wondering what the mind must be like to allow new forms of knowledge. As much as we are at the edge of the world ending, we are also at the edge of futures pregnant with possibility.

In this time of uncertainty, the thing we know without a doubt is that old methods are no longer sufficient and what is necessary to see us through are new paths to new inquiries — innovations that will function as counter-cultures and counter-measures to what has previously existed.

Hence, Afrofuturism, or more appropriately, Afrofuturism 2.0.

Afrofuturism began as a robust system of thought and immensely useful philosophy that sought to explore possible futures through the intersection of art, science, technology, history and culture. One could argue that, in recent years, it has been reduced to a collection of stylised, aestheticised and hollow tropes.

This hollowing out has rendered it ghostlike, simultaneously present and absent, looping around and reviving popularised themes and aesthetics, unable to provide new conceptions of new futures.

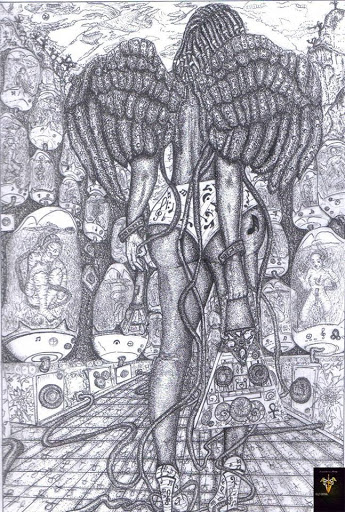

Maroon Angel of Liberation (Quentin Vercetty)

Maroon Angel of Liberation (Quentin Vercetty)

This is a fair criticism, which might, in part, explain the emergence of a second wave, or a 2.0 iteration. For those of us evoking the spirit of Afrofuturism to think through innovative ways of creating knowledge and solving problems, the challenge remains: how to ensure that our articulations of Afrofuturism reach beyond stylised versions of the past but rather function as a productive underlabourer of new ways of knowing — and of surviving.

Curating the End of the World is a series of exhibitions bringing together artists whose work responds to the Covid-19 pandemic, anti-Black violence, climate change, poor governance, trans-humanism, and an accelerating, technologically driven economic system on the verge of collapse.

Conceived by Reynaldo Anderson and Stacey Robinson of the Black Speculative Arts Movement (in conversation with Bill T. Jones and Janet Wong of New York Live Arts) and guest curated by Tiffany E Barber, the project combines technology, fantasy and critical thought to engage layers of possible futures. The exhibition is accessible through the Google Arts and Culture platform and precedes two more exhibitions, Red Spring and Dark Winter, which will follow within the year.

What follows is an excerpt of a conversation I had with Anderson and Barber about the project.

The exhibition coalesces different artists working across various mediums. I particularly love the inclusion of poetry. Can you tell us about your curatorial strategy?

Thighs in the Galaxy (Kimberly Marie Ashby)

Thighs in the Galaxy (Kimberly Marie Ashby)

As a curator, I let the artists and objects drive the shows I organise. With Curating the End of the World, from the outset we had a conceptual framework to which artists responded. But the objects submitted via the open call really informed our curatorial strategy.

This made for a diverse and expansive pool of artworks to choose from, across media — from film and video to collage and music. From the start, we were intent on including poetry and short fiction because of the role literature plays within the Black speculative imagination.

So, from the objects submitted, certain sub-themes and dynamics emerged. These overlaps happened across media and geographic contexts, which really crystallised our vision for the show.

There were also limits to the technology — at the time we struggled to find a platform that was open source, nimble and flexible enough to accommodate the multimedia nature of the exhibition. All of these factors shaped the curatorial strategy for the show.

I’m interested in how you think through the notion of speculation or Black speculative futures. What do you think this mode can offer Black people?

The artwork for Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro Blackness (Image by John Jennings)

The artwork for Afrofuturism 2.0: The Rise of Astro Blackness (Image by John Jennings)

Black speculative futurity is an emergent field of study. Outside the arts, there are applications in the area of foresight studies and blockchain technology.

First, using an Afrofuturism framework or what Lonny Brooks refers to as “Afrofuture Types”, in tandem with strategic foresight, to examine the existential risks facing Black or African populations around climate change, public health and conflict.

Second, combining the philosophy of ubuntu and blockchain technology is an economic opportunity for African filmmakers, entrepreneurs and creatives to develop their material over these platforms and not have to worry about distribution issues or piracy.

The phrase ‘the end of the world’ suggests that we have reached the climax of catastrophe, and raises questions of what happens post this climax. Does it usher a new world? What lies beyond it? Is it possible that what is beyond is nothingness?

Herald of the 5th Element (Stacey Robinson)

Herald of the 5th Element (Stacey Robinson)

The exhibition is a second-wave Afrofuturist commentary on the end of our current age. It implies that the neoliberal/postcolonial world order constructed towards the end of the Cold War and apartheid by George Bush, Mikhail Gorbachev, Deng Xiaoping and Nelson Mandela is coming to an end.

Also, it implies the New World or incoming age will be chaotic or, as Sheree Renée Thomas refers to it,“cyclical chaos”. During this transitory moment in world history, we’re interrogating the racist pathology and corruption that influences policy toward Black and Indigenous people around the world.

Finally, the exhibition looks at the global existential risks tied to ecology, climate change, anti-Blackness, medical apartheid, and acceleration in response to the dystopian present.

Sirreal (Sibusiso Xotongo)

Sirreal (Sibusiso Xotongo)

You speak of ‘second-wave Afrofuturism’. How does the second wave differ from the first?

Afrofuturism is defined by two historical moments: the end of the Cold War and the technological shift to social media and platform capitalism.

The first wave in the 1990s, coined by Mark Dery, was focused on the speculative production by African Americans and the explosion in Web 1.0 technology and internet access — all of which occurred during the era characterised as the digital divide over the gap in access to technology between racial minorities and white Americans.

In contrast, second-wave Afrofuturism or 2.0, reflects the historical background of Black speculative thought that straddles its African roots and diasporic transformation; the emergence of social media and platform capitalism; as well as the establishment of the African Union and the incorporation of the African diaspora, reflecting pan-Africanism, and the maturation of a global Black or African philosophical view of the future.

I was listening to a podcast recently and the host mentioned that as much as we speak of the global pandemic as “unprecedented times”, these times are in fact precedented (with the Spanish flu and much earlier various waves of bubonic and pneumonic plague. What is it about this moment that you believe is different? But not just different, I guess also enduring? Is this pandemic affecting artistic practices and communities in any kind of sustainable way?

What is different about this moment is the transition in capitalism and accelerating technological change. The previous pandemic did in fact kill millions world-wide during the colonial/segregation era. However, what is different is the ability of local corrupt governments or kleptocrats, as is unfolding in Nigeria, to loot resources from the community whereas previously it was directly accomplished by colonial powers. Furthermore, as is shown by the Panama papers, leaders from all over the world have been exposed transferring the wealth of their societies to offshore bank accounts with little transparency. Artists will lead the way in connecting their art to social change in this era.

Can you clarify what the viewer can expect in terms of how the project unfolds through time?

Dark Harvest (Kimberly Marie Ashby)

Dark Harvest (Kimberly Marie Ashby)

The two parts of the exhibition are intimately linked and build on one another for this first iteration. Two more iterations of similarly themed exhibitions will follow, extending the series of exhibitions into next year.

Within this initial one, we wanted to keep the objects to a set number to increase online engagement, while being very mindful of the fatigue we’re all experiencing in our new virtual reality. As you can see, many of the objects included in Parts I and II are dark in terms of their imagery, their tone and their colour palette.

These aesthetic choices resonate with the weight and uncertainty of our time. Things are heavy, unsettling, and dark right now. I just love that! I love how the objects reflect the social and political upheavals that are currently underway.

This article was produced as part of a partnership between the Mail & Guardian and the Goethe-Institut, which focuses on various aspects of innovation.