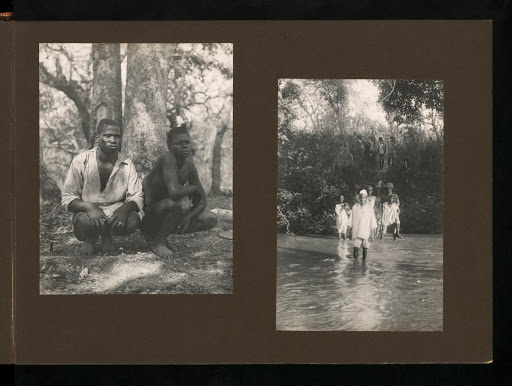

‘Kanuri’, undated. (Photographer unknown)

She sits on a high stool beside the stage, reading a contrived story of itinerant ghosts in a Nigerian hinterland. On the stage a young girl is pacing, back and forth, back and forth, holding a lamp, switching it on and off, on and off. The light at once obscures and illumines the field of my vision. The entire theatre is like a bad camera obscura. Forms flitter, images of the dancer and the girl. In each sequence, she stands from her reading stool and walks behind the young girl.

A barrier made from translucent bags obscures her from view. Behind the barrier, in the fierce redness of bright light, her body becomes amorphous, without shape — and yet I can see it transform from shape to shape. Sometimes it seems like water overflowing its banks, as though she is tempestuous sea. Sometimes she becomes a snake, crawling on her belly. Sometimes her arms, suddenly visible, flail in protest, as if struggling to breathe in a roiling sea. Sometimes her body tumbles like the wave of a giant blanket, covering an entire frame of sight — momentary blindness from too much light.

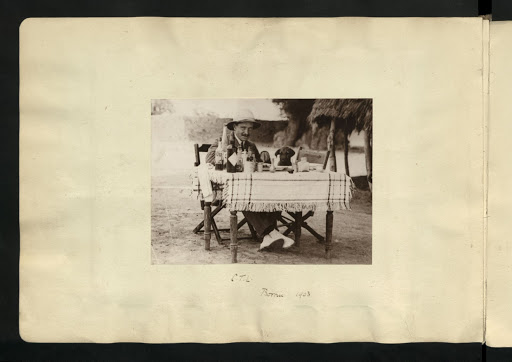

Major CT Lawrence, Bornu (Borno State), Nigeria, 1903. (Photographer unknown)

Major CT Lawrence, Bornu (Borno State), Nigeria, 1903. (Photographer unknown)

On 15 October 1925, a report by the Aeronautic Research Committee in London relayed the following: Flying-Officer Edgar Thomas O’Neil Hogben, RA, who died on 5 October at Kohat, India, as the result of an aeroplane accident on 2 October, was the son of Mrs Hogben, Elmwood, Harrogate, and of the late Edgar Hogben, MD, MRCP, and younger brother of SJ Hogben, of Katsina, N Nigeria. His age was 26 years.

At the time of Edgar’s death in India, SJ served the British colonial administration in Katsina. The nature of his role is unclear, but in 1930 he published The Muhammadan Emirates of Nigeria, a historical survey of northern Nigeria. Who knows what wayfaring ambitions had been passed from brother to brother? How long did they stand daydreaming with fingers traced along an atlas, pointing out one colony or another, speculating on which new tropical town was more conducive for British life? And perhaps, when SJ, already employed in the foreign office, brought home a gazette announcing open slots in the air force cadet programme, how did Edgar manage to suppress the premonition already filling his mind?

What I know for sure are these two paragraphs in SJ’s introduction to his book: “With the opening of the 20th century came the British Occupation. Distasteful though it may have been to the ruling classes, it saved them from the destruction from within which was awaiting them, and saved the bulk of the population from the miserable uncertainty of slave-raids and the hardly less miserable certainty of extortion and oppression.

“The country has so far stood up well to the drastic purification it has undergone. The shock of the operation, however, has been great, and the tissues must be given time to heal. One cannot leave the patient to walk unaided for some little time to come. We do not expect an infant to show gratitude to a surgeon for saving its life. We do, however, hope that when the infant grows to years of discretion he will realise that even though the surgeon draws his fees to make a living, it is his experience and advice alone which have put the patient on his legs again, and that until the cure is permanent it is as well to have the doctor close at hand.”

I am intrigued by the metaphor he uses to establish his argument: a patient, an infant and a surgeon; the sick, the unlearned and the skilled. It is beyond my imagination what life experiences he drew from to think of Nigeria as a patient-child undergoing surgery and “drastic purification”. I cannot correctly presume, although I desperately want to, that the death of his brother, only a few years earlier, informed the notion of putting a “patient on his legs again”. His brother could have survived the crash, dying after weeks of relapse. Perhaps SJ lived for the rest of his life guilt-ridden for bringing home that gazette. Oh Edgar, he grieved each time he remembered: I pointed you to your death.

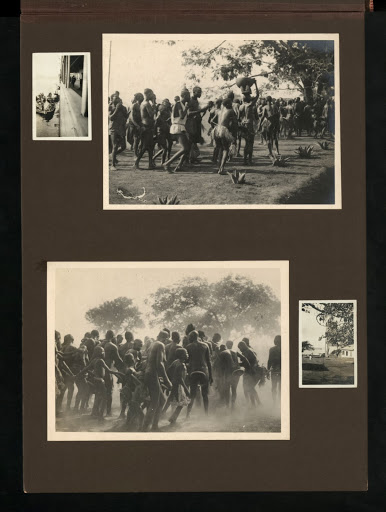

Nigeria, c 1922-23 (Photo: WF Hackman)

Nigeria, c 1922-23 (Photo: WF Hackman)

Fathers and sons, I presume, pictured in mid-movement. They perform a dance: holding, being held, circling, making rhythm. If it is a dance, then notice a trace of happiness in the incline of their bodies. Anything reduced to a trace is momentary; anything momentary might recur. Such as the glint in the eye of a man seeing a son for the first time. It is the same glint as when the boy returns home from playing, his knee grazed. The man picks up his son. Dinmkpa, he says. Grown man, strong man.

Nigeria, c 1922-23 (Photo: WF Hackman)

Nigeria, c 1922-23 (Photo: WF Hackman)

In Nyanya, a suburb of Abuja where my brother and I often visited friends of our family, in the weeks between school terms, whenever the soakaway was clogged, it was habit to rise before sunup to defecate in a rubbish dump beside a popular byroad. Sometimes the abandoned toilet still served its purpose: instead of sitting on the bowl, you placed a plastic bag on the floor, and stooped over it. Then carried your waste in the cover of darkness, and flung it into a sea of decay.

Some years earlier, also in Nyanya, when my family still lived in Abuja, armed robbers visited us. My father had just returned from the United States. On the night they came, it rained. Hours earlier my parents had returned with a stack of cash for a scheduled surgery. It is you we want, Madam, they told my mother. They asked her to point out where the money was hidden.

No one was hurt except my father. They struck his face when he knelt, perhaps sleepy-eyed, to pray (Father, forgive them, for they do not know what they do). His bloodied face would shortly be avenged. Days after the robbery my mother was invited by the police to identify the robbers. She recognised one of the men’s legs, but declined to point him out. She worried that he would seek revenge when he was released. Only that he wouldn’t. That afternoon, the police killed all the men they had arrested.

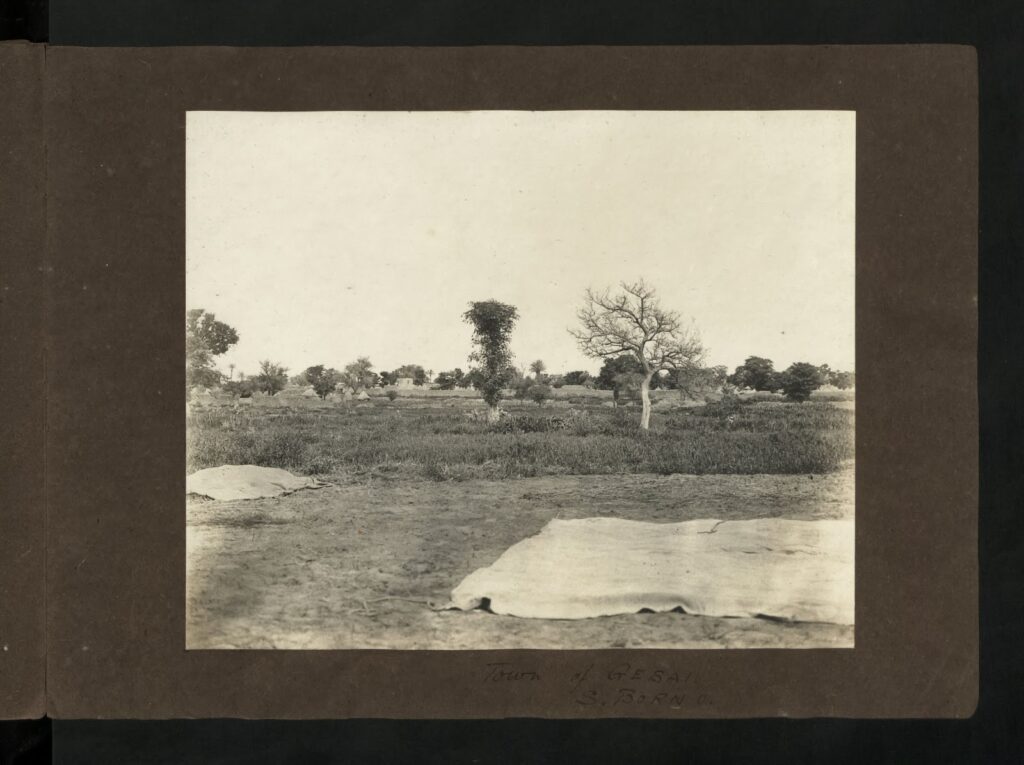

Town of Gesai, southern Bornu, Nigeria, c 1920-29 (Photographer unknown)

Town of Gesai, southern Bornu, Nigeria, c 1920-29 (Photographer unknown)

In the year I entered university, I went to visit Uncle Gabriel, my father’s friend, and his family in Onitsha. Uncle Gabriel and his wife were ministers in their church. During my visit, on a certain Wednesday after the midweek fellowship, Uncle Gabriel, unusually in a hurry to leave, was one of the first worshippers to enter the car park. A stealthy young man approached him with a gun and asked for the keys to his car, a beat-up Peugeot. One thing led to another, things turned aggressive. The man shot at Uncle Gabriel, the bullet grazing his belly. He let out a shout. The shooter fled.

A crowd of worshippers set off in pursuit and apprehended the young man. He was handed over to the police. When Uncle Gabriel went over to give a statement, an officer of the Special Anti-Robbery Squad asked him to confirm if the young man was, in fact, the villain. Yes, corroborated Uncle Gabriel. The officer was gleeful. He said the young man would not see tomorrow. Indeed, the next morning, when Uncle Gabriel visited the police station, he was shown a bloodied concrete floor in the process of being washed.

This essay is excerpted from The Journey: New Positions in African Photography, edited by Simon Njami and Sean O’Toole (Goethe-Institut/Kerber Verlag). The book is available at Bridge Books.