The Truro docked in South Africa 160 years ago. (Photo: Claude Pavard)

Struggling to make a family

A riveting YouTube social experiment called the $100 Race questions the understanding of privilege. The online video shows a diverse group of college students gathered for a 100m race. At the starting line, each student is asked to take two steps forward if they experienced what most people would call a normal family existence. If they had not experienced what was stated, they had to stay at the starting line.

Directives like: take two steps forward if you grew up with a father figure in your home; take two steps forward if you had access to private education; and so on. At the end of the instructions, the students closer to the finishing line are asked to look back. All the students stuck close to the starting line were Black.

The purpose of the experiment was to acknowledge privilege — or lack thereof. The starting point for each runner was determined by his or her social situation and from the start, it was clearly an unfair race.

The history of family life is interesting. Prior to colonial land invasion, Black people in South Africa led pastoral and agrarian lifestyles. The same was true of their indentured Indian brethren.

Indenture, like slavery and migrant labour, disrupted family and kinship bonds to advance colonial accumulation. The history of Black life from the Dutch invasion of 1652 reveals a sorry state of abnormal family life. The Natives Land Acts of 1913 and 1936 denied Black people land ownership in the country of their birth. The Group Areas Act compounded dispossession and dislocation.

For the indentured Indian, the hopes of a normal, structured family life like they had in their original homeland was a mirage. This yearning may account for the abnormally high rate of suicides. The low numbers of women recruited into indenture made family living virtually impossible. Many colonialists feared that the introduction of women to Natal would lead to a populous “alien menace”. The task of the indentured was only to provide labour and leave once the job was done.

During the first phase of indenture, 6 448 Indians were brought to the colony, namely 4 116 men, 1 463 women and 869 children. From the outset, the female quota was seen as dead stock. Over time, this attitude changed when the colonialists saw the benefits of women working hard at tasks like weeding and fertilisation. This change of attitude gave hope to the development of a family nucleus that had significant religious, social and cultural bearings.

Beyond indenture and until the 1960s, the majority of the descendants of the Indian indentured continued to experience abnormal family life that saw tens of thousands living in overcrowded barracks or extended family homesteads. Despite the barracks being periodically condemned for human habitation, these “homes” provided a semblance of normal family living.

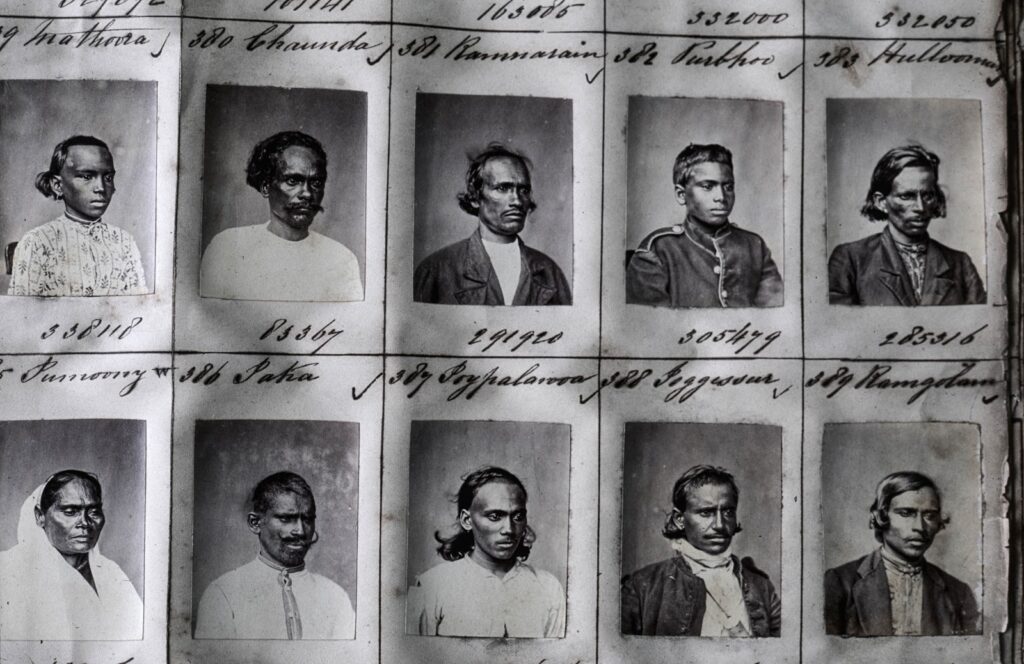

Indian workers who arrived in South Africa in the 19th century. (Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images)

Indian workers who arrived in South Africa in the 19th century. (Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images)

Mothers and wives in an extended family were responsible for keeping the family units together in the absence of fathers. Fathers often worked long hours or double shifts. The role of women in generating household income with activities like making pickles and vadas for door-to-door sale must also not be underestimated nor must their wage work in places like the textile and footwear industries. The little leisure time men had frequently invited social ills like alcoholism. That malaise extended to the township generation spawned by the Group Areas Act since the 1960s.

The comparison between the destruction of the African and Indian family by colonialism and indenture is an important backdrop to understanding many of the social issues that confront South African society. The YouTube experiment demonstrates that not everyone started the race in the same shoes.

The unifying power of food

In every culture, cooking and sharing food brings people together. In KwaZulu-Natal, biriyani is a rich metaphor to describe its people and the natural mingling of cultures and cuisines. In spite of the rigid segregation of both colonialism and apartheid, food breached the barriers.

There is every likelihood that an invitation to His Majesty’s palaces at KwaNongoma will have biriyani as one of the dishes on the menu. A visit to any farm store in the remotest part of the province will invariably turn up a packet of Rajah curry powder.

This has not been one-way traffic. Indian and Zulu people have liberally borrowed from each other’s traditional foods and cooking methods.

Picture the scene 160 years ago. Indian indentured workers disembarking the SS Truro and other vessels may have lugged a few cooking utensils and more than likely some vegetable seeds. Immediately after the beastly exercise of quarantine from which, incidentally, the colonials exempted themselves, they were shepherded to plantations very often more than 100km away. The terrain and vegetation was different from that which they encountered in either the southern or northern parts of India.

Their basic meals came in the form of rations that included dhall. Rations sometimes arrived late or not at all, forcing people to forage in the forest picking all varieties of herbs, fruit and tubers. The tasty yam called amadumbe was boiled, roasted or curried. Similarly, green bananas became fritters or grated as a curry. Mangoes could be curried either sweet, sour or pickled. Gemsquash found form as a deceptive substitute for meat or fish, especially when soured with tamarind or green mangoes.

Rice, which is a staple throughout Asia, was in short supply. Indians made amends. Mealies were pounded into fine grains. When slow-boiled it looked very much like rice. Sometimes turmeric or tamarind was added to vary the flavour. With meat either being very expensive or entirely out of reach, salted and dried fish added to a tomato chutney became a routine accompaniment to the mealie rice. In fact that simple meal has become so sought-after that one can find it on the menu of prime eating establishments like the Britannia Hotel in Durban.

A coarser ground mealie grain called samp was an established part of Zulu cuisine. Indians spiced up samp with chillies and other condiments. Curried samp, nowadays frequently cooked with beans or meat, is a prized dish.

The grinding implements are also very similar in the Zulu and Indian methods. In Tamil, the “ammikal” is a flat granite stone that is accompanied by a rolling pin type of stone. The “worral” is a standing receptacle in stone, wood or metal, the contents of which are pounded by a pole-like tool. Variations of the same are found in any traditional Zulu household.

One dish that has the same name in both the Tamil and Zulu languages is “phutu”. Its pronunciation may vary slightly but in cooking method and taste it is exactly the same dish. It is commonly eaten with a soured milk called “amasi” in Zulu, which is hardly different from the curd in Indian cooking. The curd has a cooling effect on the stomach with the probiotics aiding digestion.

The common ground in cooking traditions is potentially a fascinating area of inquiry that demonstrates that there is more that unites South Africans than divides them.

Hare Krishna devotees in Durban in 2018, during the Ratha Yatra (Festival of Chariots). (Photo: Rajesh Jantilal/AFP)

Hare Krishna devotees in Durban in 2018, during the Ratha Yatra (Festival of Chariots). (Photo: Rajesh Jantilal/AFP)

‘Coolie Christmas’

Christmas on the plantations was brief respite from the slave-like conditions of everyday life. The kutum (family) would have spent precious time together, sitting down to enjoy a simple meal. A little was a feast.

In the hundred years from 1860 to 1960, life’s journey for the majority of South Africans of Indian descent was a wretched existence. In a 1978 journal article, “The Culture of Poverty and the South African Poor”, Geoffrey H Waters estimated that 64% of Indians in South Africa lived below the poverty line. Limited employment opportunities, job reservation, successive world wars, colonial and apartheid-era depredations together with depressed economies, all contrived to keep the turkey and ornately wrapped presents at bay. An assessment of African livelihoods would have made for similar if not more depressing reading.

Historically, Christmas was not celebrated on the plantations as the majority of workers came from rural parts of India, where Christmas was not a big event.

Bizarrely, the colonialists referred to the festival of Mohurrum as the “Coolie Christmas”. Mohurrum championed hybridity, as opposed to theistic exclusivity.

Muslim reflections of saintly martyrdom, together with Hindu ritual practice, merged into a show of brotherhood that only circumstance could create. Caste, religion and creed were left behind in the ports of India to fashion a new consciousness.

Indenture brought with it many unintended outcomes in the broader religious and sociological narrative.

This is an edited excerpt from The Indian Africans by Paul David, Ranjith Choonilall, Kiru Naidoo and Selvan Naidoo, published by MicroMega to mark the 160th anniversary of the first Indian indenture in South Africa