Philosopher John Gray has written a delightful book on cats and the meaning of life. (Photo: David Levenson/Getty Images)

“I like books and cats and books about cats,” my Twitter bio proclaims. I confess, however, that during this catastrophe of a year, I have relied more on the comfort of my feline friends than on the pleasure of the written word.

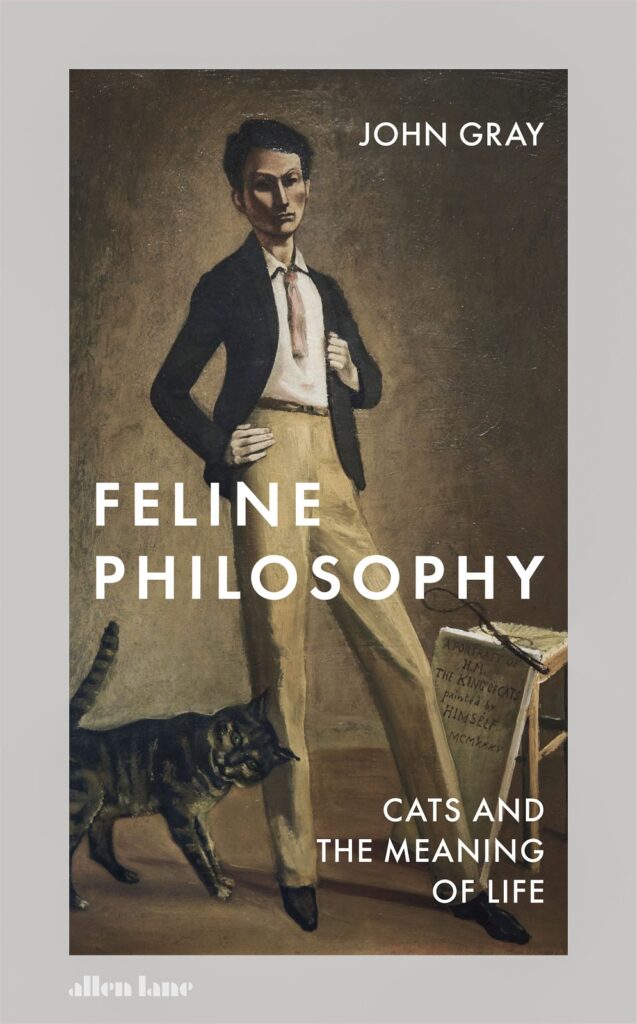

Imagine having to “psych yourself up” to read a book. For me, at least, this notion seemed outlandish but, like so many events of 2020, what was once inconceivable has come to pass. Nevertheless, when a copy of British author John Gray’s Feline Philosophy: Cats and the Meaning of Life landed in my inbox, I duly pounced on it.

As befits its subject matter (and helpful for my current reading block), Feline Philosophy is a slim volume, running to 120-odd pages. Cats are not creatures to waste their energy.

Gray, who took early retirement from academia to focus on writing more “directly engaging” books, says his primary reason for writing this particular one was to express his love and admiration for cats. In addition, “One of the motives was to say what I’ve learned from cats, but, having been a philosopher, I wanted to express some doubts or scepticism about philosophy itself,” he tells me over Zoom.

Feline Philosophy focuses just as much on philosophy as it does on felines. Gray takes us through a potted history of (mostly) Western philosophical traditions, with some forays into Taoism and Buddhism, as he interrogates the human quest for meaning.

There’s plenty to ruminate on in Feline Philosophy, which also contains a useful introduction to some of the traditions of Western philosophical thought. (Penguin Random House)

There’s plenty to ruminate on in Feline Philosophy, which also contains a useful introduction to some of the traditions of Western philosophical thought. (Penguin Random House)

Humans are anxious beings — both conscious of our own mortality and forever trying to displace this anxiety with endless diversions, including philosophy itself, to ward off thoughts of death.

This self-awareness, and the anxiety it engenders, is uniquely human. Where philosophers differ is in their assessment of this condition. Here Gray follows the philosopher Michel de Montaigne, who views our capacity for consciousness not as evidence that we are superior to the rest of the animal kingdom, but as a marker of our own flawed nature.

“To meow or not to meow, that is the question” was my working title for this article before I interviewed Gray, and before I had even read the book. On reading it, I realised my headline idea had missed the point entirely: cats’ lack of self-awareness means they do not spend any time questioning the meaning of life (or, indeed, their nine lives).

In fact, as Gray notes, unlike some other animals (humans among them) cats do not pass the mirror self-recognition test, which, as its name suggests, means they cannot recognise their own image. Not knowing themselves in this way allows them the freedom of not spending their lives confronting their existence (and ultimate demise). To put it in other words: for cats, chasing their tails is just that; an amusing physical activity, rather than the signifier of a metaphysical conundrum.

Author of Feline Philosophy, John Gray, says his cat Julian most enjoyed the ‘sheer sensation of being alive’. (Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

Author of Feline Philosophy, John Gray, says his cat Julian most enjoyed the ‘sheer sensation of being alive’. (Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

Covid-19 has thrown our human tendency to try to assert control over our lives by telling stories, and making meaning, into sharp relief.

Notwithstanding the pandemic’s real-world implications, one of the most difficult “meta” aspects of living through it is the uncertainty it creates. Even with vaccines starting to be rolled out, we don’t know when the virus will be brought under control; when we can begin to live in a “new normal”. On top of this, under varying levels of lockdown, many of our usual distractions for coping with the vicissitudes of life are unavailable.

As we grapple with this situation, we could do worse than attempt to emulate the feline approach. The trick is not to get tangled up in the anxiety that arises from overthinking our present circumstances or worrying about imagined future terrors. “Cats do not plan their lives; they live them as they come,” Gray writes. “Humans cannot help making their lives into a story. But since they cannot know how their life will end, life disrupts the story they try to tell of it. So they end up living as cats do, by chance.”

Speaking of his cat Julian, who lived for 23 years and died just before last Christmas, Gray says, “The sheer sensation of being alive is what he enjoyed the most. And that had a big impact on me. If you ask: ‘How can human beings be happier?’— the answer is not by thinking about happiness … If you want us to learn from cats; if you want to ‘enjoy’ lockdown — go for a walk: don’t think about it.”

During South Africa’s level-five and -four lockdown, I was living by myself, housesitting for my parents, who had been stranded on holiday. I must admit, I rarely had the energy to take myself on a walk (even when this was allowed).

Writer Theresa Mallinson’s cat, Jasper, may find the human search for meaning absurd, but is not above striking a philosophical pose herself. (Clea Mallinson)

Writer Theresa Mallinson’s cat, Jasper, may find the human search for meaning absurd, but is not above striking a philosophical pose herself. (Clea Mallinson)

But I wasn’t entirely alone — our cats, Jasper and Opal, offered me their special brand of succour. Whether they were playing “giddy kitties”, showing off their finest feline dribbling skills with a ping-pong ball, or snuggling on my lap while they kneaded my knitting, delighting in their presence took me out of my head. I was able to cast aside, if only temporarily, the worries of the work day, the unfolding horror of the pandemic and the more general existential dread that is our human lot.

A few years ago, my sister Clea, in the grip of what we term “the kitten yearning”, posted on Facebook: “Sometimes I wonder: Do I want to get a cat, or do I want to be a cat?” Much as this struck a chord with me, pondering such questions, a quintessentially human activity, takes us ever further away from becoming catlike. A cat does not wish to be that which it is not, but is content to live within its nature.

“Humans are humans; cats are cats,” as Gray notes both in Feline Philosophy and during our conversation. “We can’t actually live like cats. We can learn how to live better as humans, from cats, because they don’t have the particular maladies that humans have of worrying about the future, living in their imagination, fearing death a lot … We can’t, kind of, be like them … but we can, perhaps, learn from them why we are as we are, and to live a little more like them.”

At the heart of the book is a paradox: one of its conceits is imagining what a hypothetical feline philosopher would make of it all. “If cats could understand the human search for meaning they would purr with delight at its absurdity. Life as the cat they happen to be is meaning enough for them,” Gray writes.

During our conversation, Gray elaborates on this concept. “Cats don’t need philosophy: they already know how to live. So there aren’t any feline philosophers,” he says. “And even if cats could do philosophy, they might not bother. And even if they did do it, they wouldn’t care if anyone followed their advice.”

That said, there’s plenty to ruminate on in Feline Philosophy. It’s the purrfect addition to any ailurophile’s bookshelf, and also a useful introduction to some of the traditions of Western philosophical thought.

Could cats read, I imagine they would devote their time only to those books with a certain ludic quality, a lightness of touch. Gray deftly captures such a tone and it feels as if there’s an aphorism on almost every page. I’ll leave you with this one: “We pass through our lives fragmented and disconnected, appearing and reappearing like ghosts, while cats that have no self are always themselves.”

Ten feline hints on how to live well

1. Never try to persuade human beings to be reasonable;

2. It is foolish to complain that you do not have enough time;

3. Do not look for meaning in your suffering;

4. It is better to be indifferent to others than to feel you have to love them;

5. Forget about pursuing happiness, and you may find it;

6. Life is not a story;

7. Do not fear the dark, for much that is precious is found in the night;

8. Sleep for the joy of sleeping;

9. Beware anyone who offers to make you happy; and

10. If you cannot learn to live a little more like a cat, return without regret to the human world of diversion. — John Gray