Thobani K’s first portrait, an image of his grandfather Bhekindaba Killiam Cele, sets out his modus operandi.

In the 1980s in the then KwaZulu homelands, the areas of KwaNgcolosi, Emaphephetheni and EmaQadini (Eskebheni) were flooded when the Inanda Dam overflowed, disrupting the lives of residents, many of whom lost their homes and small businesses.

One local businesswoman, who owned the Umngeni Drift Store, had a paddle boat which she used to assist locals to cross the Umngeni River to the Ngcolosi area near Molweni. Because of this crucial boat, the Umngeni Drift Store was referred to by the people as Eskebheni (“by the boat”), and even Dusi Canoe Marathon participants used to camp in the store’s yard.

Her properties, along with cars and vast areas of land, were buried in the floods, forcing her to relocate and rebuild.

This businesswoman is Nomusa Khumalo and she is the grandmother of photographer Thobani Khumalo, professionally known as Thobani K. He tells this story as soon as he arrives for our interview, distinguishing his hometown as “not Inanda, but Eskebheni.” This tale of loss, family and landscape informs much of Khumalo’s photography today.

Thobani K’s grandmother Nomusa Khumalo

Thobani K’s grandmother Nomusa Khumalo

Trajectory of style: family first

Khumalo’s first portrait was of his late grandfather, Bhekindaba Killiam Cele, in 2015. Khumalo explains that his deep respect for his grandfather’s family tradition inspired the image: “He respected my grandmother from my maternal side. He’s an example of saying, ‘I didn’t just marry you, I married the family.’”

The portrait of Mr Cele is black and white, with him in a suit, reading the Mail & Guardian instead of Isolezwe: Khumalo chooses different newspapers for Western and vernacular audiences.

“I put him in a suit, in the kraal with his cows,” he explains, to juxtapose modern dress with a rural setting. “Cows, to me, and the way they are viewed among the black community, is that they represented a primitive stance.”

This portrait set Khumalo’s photographic mission: to iron out his dissonance regarding traditional-rural and urban worlds.

Form and content as projection: the chicken portrait

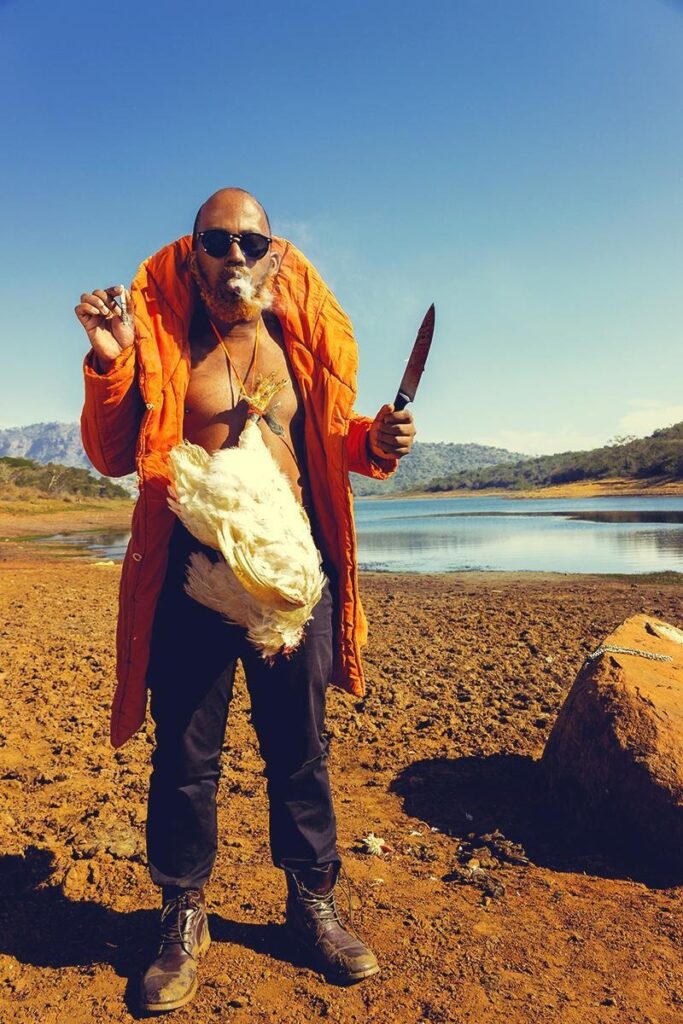

Images of younger creative acquaintances contrast sharply with the intimacy of Khumalo’s grandfather’s portrait. In a particularly brazen example, a cloud of smoke exits the mouth of a man with a cigarette in one hand and a butcher’s knife in the other. A chicken dangles on a rope around the man’s neck, while a gold chain rests on a rock to his left. There is no intimacy this time.

“I was kind of in a dark space,” Khumalo reflects on his mind state when he made the image. “I tried to nail something I was going through in my life. I am so exposed to being told I can’t be anything if I don’t slaughter an animal, if I don’t see a sangoma or inyanga and drink something.”

Images of younger creative acquaintances contrast sharply with the intimacy of Khumalo’s grandfather’s portrait. (Model: Simphiwe Xulu)

Images of younger creative acquaintances contrast sharply with the intimacy of Khumalo’s grandfather’s portrait. (Model: Simphiwe Xulu)

Heritage is an awkward theme in Khumalo’s work, as ancestral duty tangles with his consciousness and knowledge of self.

Use of colour: blue background portrait

Khumalo’s images are either saturated with colour, or black and white. The former are vibrant and overwhelming, exaggerating the subjects’ form and surroundings. In one such portrait, an alarmingly blue wall pulls focus from a figure in a thrifted shirt, using Steve Biko’s I Write What I Like as a parasol. Their lips are rose-red; their skin is grey; the cloths they hold are plaid and their right elbow rests on a traditional grass mat. The colour celebrates life. There is excitement and zest in the image.

Thobani K’s images are either saturated with colour or black and white. (Model: Ayanda Ntombela)

Thobani K’s images are either saturated with colour or black and white. (Model: Ayanda Ntombela)

The element of water and his process

Khumalo says, “Most of the time, you might notice, I shoot next to water.” His family’s long relationship with bodies of water — as vistas, roadways and even death traps — has shaped Khumalo’s photos.

He does not, however, always seek out landscapes with water (“It’s not like I do it consciously”) but there is a spiritual connection with water, which he seems to often return to in colour and as physical locations.

Thobani K’s work hints at a spiritual connection with water. (Model: Mbali Fikeni)

Thobani K’s work hints at a spiritual connection with water. (Model: Mbali Fikeni)

All the elements together

Khumalo’s latest body of work delves into the grey water issue in the eSkhebeni area. It is photojournalistic in style and content, but still connected to Khumalo’s family history, as well as the politics of land and water: “I look at the water situation: to me that is water apartheid, the fact that Durban North, Umhlanga, they have a water service system that is different to the one in eSkebheni; they’ve got a sewerage system, but if you go to Emzinyathi, Inanda, we don’t have tap water. We have useless grey municipality tanks that do not have water and now water trucks are the system and source of accessing water.”

Khumalo’s style is informed by personal experience, family history and tradition as well as the sociopolitics and spiritual power of water. Every life experience — from his grandmother’s stories onward — influences his construction of an image.