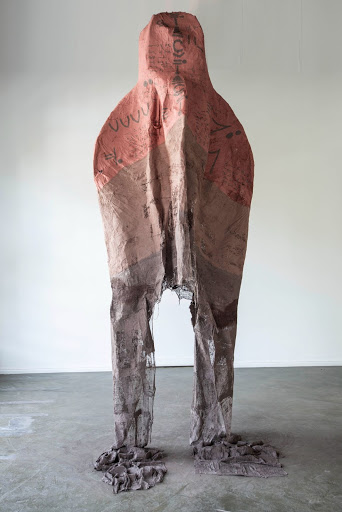

Cow Mash’s Boleta le Bofefo, 2019-2020. (Polyester resin, faux leather, various synthetic fibres, found object, 97 x 135 x 315 cm)

Circa 2010, artist Tracey Rose published a performative text titled ArtHole: Readings From Within the Abyss, in an issue of Art South Africa magazine (now renamed Art Africa, it is seemingly dedicated to the often overlooked topic on the writings of visual artists). Interestingly, Rose’s text wasn’t an article in the traditional explicatory sense, but rather a repetitive use of the word “white” throughout the piece, and more than a thousand times.

As non-explicatory as it was, I considered it thought-provoking. Behind the performative dimension was a blatant reminder, not only of the default preferment of white artists, but also the overrepresentation of art authorship as primarily white. Although the editor acknowledged that Rose’s text was “a reminder that we/I need to get our/my house in order”, the irony was that the same editorial note only named and exclusively recognised the writings of white artists.

Pyda Nyariri’s Pidgin’s cocoon as sounded out with inverse intonations, 2021. (Clay slip, cotton gauze, plywood and hardware, 300 x 147 x 100 cm)

Pyda Nyariri’s Pidgin’s cocoon as sounded out with inverse intonations, 2021. (Clay slip, cotton gauze, plywood and hardware, 300 x 147 x 100 cm)

Excited by how Rose’s move laid bare the dirty laundry of art writing and publishing, I showed it to a friend, who unfailingly considered the visual arts space as akin to a contemporary tableau vivant of plantation life. His response was simple, but pointed: “Why white and not black black black?” I had to pause. His irritation came from the conviction that racial whiteness is a capacious ideology that not only reproduces itself under the veil of condemnation but also does so with the explicit intention of de-emphasising any other view.

Phoka Nyokong’s Museamo wa Bogodu (The Museum of Theft), 2020. (Oil on Fabriano Artistico, 76 x 145 cm)

Phoka Nyokong’s Museamo wa Bogodu (The Museum of Theft), 2020. (Oil on Fabriano Artistico, 76 x 145 cm)

Black Luminosity — a group exhibition curated by Gcotyelwa Mashiqa at Smac gallery, Stellenbosch — posited that other view by revisiting the chromatic and social properties of blackness in contemporary South African visual art. The show brought together a group of about 10 contemporary artists, working in different media (sculpture, painting, drawing, mixed media, installation, photography and so on) into an intense visual dialogue on the matter of blackness.

For scholar Simone Browne, from whom, I imagine, Mashiqa takes the title, black luminosity is about technologies of racial surveillance and slavery. In fact, Browne uses black luminosity differently, that is, “to refer to a form of boundary maintenance occurring at the site of the racial body, whether by candlelight, flaming torch or the camera flashbulb that documents the ritualised terror of a lynch mob”.

Mary Sibande’s Good is bad and bad is good, 2020. (Oil on bronze, 68 x 34 x 34 cm_Edition of 6 +2 AP)

Mary Sibande’s Good is bad and bad is good, 2020. (Oil on bronze, 68 x 34 x 34 cm_Edition of 6 +2 AP)

But Mashiqa seems not to be coming at it from this angle at all. Instead, she takes a page from feminist scholar Tina Campt’s notion of black visuality as a practice of refusal, and by which she foregrounds how the “opacity or Blackness of each artwork becomes a site of critique”; that is, a critique of how works of art deconstruct “the clichés and stereotypes associated with the pigment and formation of Black”. The exhibition not only “aims to reveal the unseen”, but also seeks to interrogate the cultures of seeing and the predisposition to stigmatise blackness.

The title Black Luminosity itself invites a kind of musing on the politics of colour. As a nominal stroke, it names an adversarial praxis poised against what convention might consider conceptually untenable. As a visible physical characteristic, colour interestingly traces its origins within a family of words denoting a kind of coating that registers light.

Although the colour white conceptually stands in an empty place in the colour charts, its importance cannot be overstated. Whether as a priming surface or neutralising agent, white (unlike black) acquires the status of indispensability. Thus, for film critic Richard Dyer, “White is no colour because it is all colours.” In other words, Dyer notes further, it is simultaneously nothing and everything, perhaps just as racial whiteness navigates the world as both “particular and nothing in particular”.

Musa N. Nxumalo’s Story of OJ, After 4-44 (Simiato Matik), 2020. (Archival pigment print on hemp linen_160 x 130 cm_ED 1-3_2 AP)

Musa N. Nxumalo’s Story of OJ, After 4-44 (Simiato Matik), 2020. (Archival pigment print on hemp linen_160 x 130 cm_ED 1-3_2 AP)

In line with Jared Sexton’s argument, blackness, in the chromatic plane, exists as a presence without colour, relationally poised against whiteness as a colour of absence. And since colour qua light is regarded as the natural derivation of life, by “presence without colour” blackness is the emblem of death — of nothing — almost like the darkness that preceded creation.

In occidental visual culture, particularly of the early modernist period, blackness is directly deployed as a mark of temporal obsolescence and ignorance. Art historian Tim Clark, for example, reads the subtle break of colour from absolute dark (right to left) of the empty background in Jacques-Louis David’s 1793 painting, The Death of Marat, as the beginning of modernity.

In the work of Russian abstractionist Kazimir Malevich in 1915, under the guise of the autonomy of form, black assumed pigmentary primacy but had no utility outside its negative, racial difference. Using the latest technology, in 2015, it was revealed that beneath the black surface of one of Malevich’s monochromatic Black Squares, there was a hand-written inscription saying: “Negroes fighting in a cave at night.” The annotation rewrote a racist witticism that formed part of the Russian literary scene. For critic Hannah Black, these racist instances reveal more than just the artist’s negation of representation, but also how negation itself calcifies into a form of representation.

Wallen Mapondera’s Untitled, 2021. (Toilet paper and cardboard on board, 90.5 x 131 x 12 cm)

Wallen Mapondera’s Untitled, 2021. (Toilet paper and cardboard on board, 90.5 x 131 x 12 cm)

This is certainly not Mashiqa’s project. If anything, hers is to counteract this tendency. Nevertheless, we must ask: How does a property deemed virtually absent of light, radiate light? This is a thought-provoking riddle. Perhaps the first step is akin to what Ralph Ellison poetically describes in Invisible Man when he writes: “I did not become alive until I discovered my invisibility.”

Discovering the light of blackness might need us to tarry with the chromatic and social defects of blackness, as it were, to see our world in total darkness. Take, for example, how the use of ultraviolet lamps (black light) in the contemporary visual art in the past decades or so has also elicited a critical commentary on antiblackness and its dominant visual technologies of display.

More recently, similar shows have been curated, namely: Young, Gifted and Black at the Goodman Gallery and A Black Aesthetic: A View of South African Artists (1970-1990) at the Standard Bank Gallery. Both shows, curated by young black practitioners whose stamp in contemporary visual art is uncontested, had the explicit aim of casting a positive valance on black artistry, sensibility and historical experience.

Stephané Conradie’s slagoffer, 2021. (Mixed media relief assemblage, 45 x 42 x 16 cm)

Stephané Conradie’s slagoffer, 2021. (Mixed media relief assemblage, 45 x 42 x 16 cm)

Mashiqa herself, who is part of the crop of young and exciting black curators, cut her curatorial teeth as an intern curator at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa some years back. Black Luminosity forms part of the trajectory of these exhibitions, even though its point of departure appears lightly abstract and object-oriented. On one side, it places primacy on blackness as a non-hypostasised “colour” before its representations in the semiotic order; on the other, it traces the effects of blackness in the strategic commentary and invocation in the visual object. In other words, not every artwork in the exhibition is necessarily black or overdetermined by a black pigment.

The recent turn to the “colour” black in contemporary visual art might be, at first glance, surely participating in the much-needed critical commentary on the pervasive disregard and incredulity towards anything black. But there’s also the added complexity in that much of the work draped in black is increasingly getting caught up in a cyclical, monotonous fashion that is incongruent with the aspiration for critical participation. As contemporary art’s latest craze, this recurrent motif is progressively and spontaneously assumed to be the metonym for antiracism, when in other instances it is not.

Pieces such as Cow Mash’s sculptural piece Boleta le Bofefo, Zandile Tshabalala’s painting Self Check: Lady in a Pink Scarf and perhaps Alexandra Karakhashian’s series of paintings, are exemplary of this pigment-centric focus. Using everyday materials (soft and hard) to poetically construct a hybrid feminine creature seemingly pulling a strange wheelbarrow, Cow Mash’s sculpture portrays an interesting analogy between the domestication of livestock and the dynamics of the gendered labour of captive lives. However, what I find concerning about this piece is that I cannot, for certain, read if it feigns a celebratory “work scene” of the black woman’s strength or not. As for the rest, from Mary Sibande, Usha Seejarim and Phoka Nyokong to Wallen Mapondera and others, they enter into the dialogue somewhat differently.

Usha Seejarim’s Halo, 2021. (Reclaimed ironing bases, steel. 83 x 125 x 22 cm)

Usha Seejarim’s Halo, 2021. (Reclaimed ironing bases, steel. 83 x 125 x 22 cm)

Seejarim’s intriguingly titled sculptures Art History at Home and Halo use unconventional, but nevertheless contextually apposite, materials to their subject matter, while also raising concerns about the place of women in prevailing knowledge paradigms, be it art history or theology.

Mapondera’s untitled installation piece also manipulates everyday materials like toilet paper (expensive and cheap) to make a compelling point about the debasing and dispensability of women’s bodies. He neatly frames the toilet paper inside cardboard, as one would an art work, as if to gently pass an indictment about the misogynistic practices within the art world itself. The work is presented on a table/board game-like suspended structure, with a single chair at one of its sides as if to cater to one seeking solitude and an enjoyable game.

Zandile Tshabalala’s Self Check Lady in pink scarf, 2021. (Acrylic on canvas, 120 x 90 cm)

Zandile Tshabalala’s Self Check Lady in pink scarf, 2021. (Acrylic on canvas, 120 x 90 cm)

However, it was Luyanda Zindela’s portrait of his mother that I kept coming back to. The old lady is reclining in what looks like a hospital bed, with her arms placed behind her head. With a calm face, she looks at us, non-judgmentally. I recall wondering to myself, what had become of her.

Though the question of blackness is foregrounded by these works, gender and sexuality clandestinely operate in the background, informing and tying most of these artworks together. Overall, BlackLuminosity, which ran until 20 May, was certainly a thought-provoking exhibition that must explore the possibility of a second iteration to fully flesh out its thoughts and curatorial mission.