Orgasmic State, 2021 (Oil and acrylic on Fabriano, digitally printed on cotton rag)

Recently, after years of working as a photographer and filmmaker, Khubu Zulu began painting. She had delayed the psychotherapy needed to alleviate the post-traumatic stress disorder related to covering the Fees Must Fall protests.

“I couldn’t deal with what was happening to these children,” she says from the small interior of the Godart Stokvel Gallery, in Albert Street, Johannesburg. “And I wasn’t at a point where I could visit a doctor, even though I had doctor friends.”

At some point, she says she decided, “You know what, I can’t let this thing defeat me. I went into what became my studio. I had materials because I’d been meaning to do paintings and I had been doing some drawing. I just got in and got started. It was probably like noon and I went on until midnight. And I’d started three pieces.”

Orgasmic State II, 2019. (Oil and acrylic on Fabriano, digitally printed on cotton rag)

Orgasmic State II, 2019. (Oil and acrylic on Fabriano, digitally printed on cotton rag)

Zulu must have tapped into a powerful, latent creative force, for there is quite a gulf between those initial pieces and the bulk of the work showing at the gallery, which she has titled Aftermath.

Aftermath brings together digitally printed black-and-white photographs, as well as digital prints of mostly small-scale mixed-media works (usually charcoal, oil and acrylic works on paper and canvas). Zulu tends towards abstraction, bright colours and evocative, beautifully treated surfaces which, in some cases, involve experimentation with methods associated with printmaking.

Although mostly small in scale, the editioned works are grand in theme, with Zulu’s locus of concerns taking in the role of the sky, cattle and ancestry in Zulu cosmology; pollution and toxic waste (especially along south Durban’s harbour-adjacent residential areas); and the human cost of the barbaric spatial planning and labour practices of the apartheid regime.

Disfigured, 2021. (Oil and acrylic on Fabriano, digitally printed on cotton rag)

Disfigured, 2021. (Oil and acrylic on Fabriano, digitally printed on cotton rag)

Partly because Zulu was new to the artform, an unabashed predilection for experimentation has given her work an uncanny, intuitive thrust, often lending a sense of viscerality to her thematic concerns.

“The green, the yellow, the purples, the blues … that’s kind of how petrol looks,” she says, tracing her fingers over the contours of Orgasmic State, a striking, large-scale work taking up roughly the space of a human torso. “When it’s coming from the ground as a raw material, it is usually black.”

Zulu recalls trips to her cousins as a child, and how the odour of the chemical would dominate the smells of their morning routine as they readied themselves for church.

“It’s sort of like an orgasmic state, the feeling,” she says, inhaling exaggeratedly.

“As a child I wouldn’t have [called it that] but as an adult, interpreting that for myself, the smells … especially when you have hunger pangs, because that was the first thing we’d encounter in the mornings in Wentworth. It’s almost kind of sweet, but it isn’t really. At first it seems kind of seductive, and then it’s like bilious.”

Her mention of the raw state of petrol is significant. The colour black (from charcoal markings) seeps to the surface in Orgasmic State, and is more clearly visible in some of the other works.

In a work titled Liquorice, there is a lovely, almost isolated splotch of black, rendered ethereal by the printing process. “Again, thinking about it as a child, going through South Coast Road by bus, you’d get that odour that comes … That’s why there’s another three called Liquorice,” Zulu says. “It’s like, ‘Okay, I’m taking four buses a day but I’m gonna eat my liquorice when I’m on that bus through Clairwood because the plan is to have a taste that counters that smell …’ Not that it did, because it’s there.”

Ses’fikile – Sacrifice, 2021. (Oil and acrylic on canvas, digitally printed on cotton rag)

Ses’fikile – Sacrifice, 2021. (Oil and acrylic on canvas, digitally printed on cotton rag) Oil and water

At some point, Zulu says her formal process somehow mirrored her thematic focus, and she looked at the work of Francisco Goya, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Gerard Sekoto as she sought a language. She stubbornly mixed oil paint with acrylic, at some point forgoing conventional wisdom around priming and layering techniques, resulting in cracked surfaces and uneasy congealment of the materials. “It was an experiment for me, because I’d never mixed oil and acrylic, but it was also because I wanted to make a point about the climate crisis. You know, oil and water don’t go [together].”

If there is a kind of accidental beauty and claustrophobia to the mixed-media works developed on paper, Zulu’s works on canvas, also digitally reprinted, breathe, and are a tad more deliberate in execution. Her backgrounds are more monochromatic, shifting the focus to the sky, or the cosmos, with a central, dominating figure that is at times human-like and, on occasion, bovine. “I wanted to show how the light changes in the sky, because it doesn’t start off with being blue,” she says. “For me, if a figure appeared unplanned while I was painting, then I’d incorporate those little accidents that appeared.”

On some of the canvases, Zulu conducts a different set of tests, manually superimposing the contents of her wet canvases onto fresh, dry ones to produce a series of “prints”. She’s quite enamoured with a work called The High Priestess, a regal, abstract figure evoking a kind of precolonial poise. “There’s an androgyny about it: a direct reference to myself,” she says. “My parents wanted boys.”

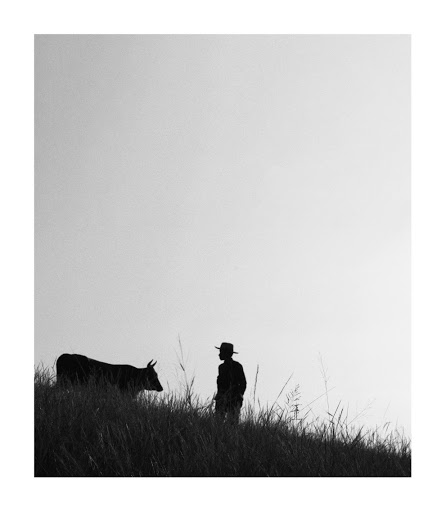

Siyathandaza, 2021. (Image digitally printed on cotton rag)

Siyathandaza, 2021. (Image digitally printed on cotton rag) It makes sense for Zulu to place these works in proximity to a string of photographs depicting pastoral scenes in kwaNongoma (in KwaZulu-Natal), in which she plays both photographer and something of a matador figure. The framing of some of the images, again, draws attention to the heavens and associated hovering bodies. Her sense of timing animates some of the photographs. There is one of a cow mooing in an open field, taken from an oblique image, titled Yakhal’ inkomo.

While there is still a detectable self-consciousness when it comes to pulling harder at the discursive threads offered up by her work, considered together, the photographs and the mixed-media works suggest Zulu to have delved wholeheartedly into the meditative properties of creating.

Ensconced in a new vocation, she has found a sliver of light with which to process both childhood and adult traumas. The works have the drive of an artist on the verge of hitting their stride, while seeking ways to circumvent the prohibitiveness of starting a new practice from scratch. Although she created in solitude, there’s a feeling that Zulu is not walking her path alone.

The exhibition runs until June 20.