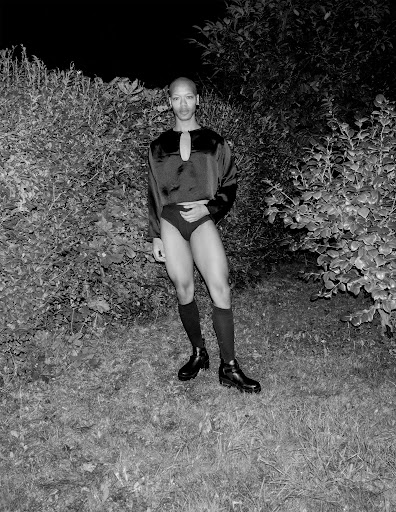

A negotiation: Nakhane, pictured in their garden in London in October, 2021. (Photos: Nakhane)

Queer bodies have always occupied artistic and cultural spaces, from Michelangelo and Anaïs Nin to James Baldwin, Audre Lorde and Brenda Fassie, to modern-day music-makers such as Moonchild Sanelly and Janelle Monae.

Nakhane, star of the film Inxeba, playwright, musician and all-round maverick of the arts, is arguably one of the biggest contributors to our understanding of the eclectic world around us. They’ve been lauded by Elton John and Madonna, and with an array of offerings in fields including film and literature, they are becoming one of the titans informing South Africa’s cultural tastes.

The artist says being queer in South Africa offers legal protection, but lived experiences can be brutal and frightening.

The artist says being queer in South Africa offers legal protection, but lived experiences can be brutal and frightening.

How would you describe yourself?

Well, this is a hard one. I’ve always understood that identity is an ever-changing spectrum, but in that there is still a centre, a core that is identifiable as “you”. In its simplest form: I’m Nakhane, a Xhosa, non-binary, pansexual, artist.

I wish we lived in a world that didn’t need all this labelling, but unfortunately we have seen that if people don’t hold on to their identities then they are erased. The labels also give us community, and the understanding that we are not alone.

How would you describe your work?

My work is an exploration of memory, sexuality, race, pain. Of course, it’s not only that. Sometimes it spreads out, at other times it shrinks.

When I really have to think about it, at its simplest I would say my work is a glorification of historically vilified people. They take centre stage, their stories are told, they are allowed to be sad, to not be strong, to be vulnerable; but at the same time, be powerful too.

Is there an intersection between your work and your sexuality?

Yes and no. Yes, because I write stories that reflect characters that are not necessarily in the mainstream. From a selfish point of view, I write characters that look like me and my friends, and my family. These are people that have been deemed not worthy of art.

No, because the work itself doesn’t have an identity. It’s not “queer music” or “queer literature”. I find that ghettoising.

Intersection: On one level, Nakhane writes characters that are not in the mainstream, but that look like themselves, their friends and their family.

Intersection: On one level, Nakhane writes characters that are not in the mainstream, but that look like themselves, their friends and their family.

When it comes to engaging your work, what do you want people to take away?

I have no control over what people will take away from the work. I remember when I was in school our drama teacher always said that once you have put the work out there, then it’s not yours anymore. It’s one thing to hear that from a teacher and it’s another to actually give away something you’ve been working on for years. The audience must have the right to take whatever they want from the work.

The only time I’ve intervened was when there was a problematic misunderstanding. For example, there were some people who thought that my song, Presbyteria, was about interracial relationships or sex. Of course there’s nothing wrong with interracial relationships or sex, but there is something wrong with thinking that they are more elevated than intraracial relationships or sex. So I stepped in.

What are your thoughts about the more controversial aspects of your work?

I don’t understand what is so controversial about my work. I’ve never made something and thought, “Ooh, this is going to be so controversial.” So on some level, I’m always surprised when it’s labelled as that.

“I also wanted to problematise writing about sex for myself,” Nakhane on writing for the anthologies Touch and Exhale

“I also wanted to problematise writing about sex for myself,” Nakhane on writing for the anthologies Touch and Exhale

How does work such as yours and other queer folx play a role in adding to a greater cultural narrative?

Well, it always has. Queer people have informed so much of what we take for granted in culture. It’s just that those people were either unable to be themselves or there was some straight person who appropriated that work. How is culture going to be rich, complex, varied, et cetera, if it’s just from one type of person?

How was it writing about sex (for the books Exhale and Touch)?

I loved it because I got to explore different strains of writing: fiction and nonfiction. In this exploration I also got to play with the intersection between these two forms of writing. Where does one end, and the other begin? It was really fun blurring those lines. Hiding autobiography behind the mask of character in fiction; and then magnifying imagination by using a small level of evasion and obfuscation in nonfiction. I also wanted to problematise writing about sex for myself. What did I want to read? What was it that I was ashamed of, and was I willing to commit that to paper?

What do you feel about how queerness, in Africa and on the continent, is held within the artistic realm?

This is complicated. On one hand you have legislation, and on the other you have the so-called real world. In some countries the law is brutal towards queer people, but then in the “real world” there is an unspoken … I don’t want to say “acceptance”, because that should be total and unconditional, but an understanding that queer people exist. And then you have a country like South Africa, where the laws are incredible, but the “real world” is a much more complicated and often brutal experience.

I’m angry that our existence has to be a negotiation. I’m angry that what we do with our lives is seen as something that should be other people’s business. We’re not forcing them to be queer. Why do they care so much?

What are you working on?

My second novel, a miniseries, a short film. I’m awaiting the confirmation of when my album will be released. And I’m also working on a separate collaborative music project.

Are you fucking fabulous?

There are times when I want to be, and there are other times that it just feels superfluous.