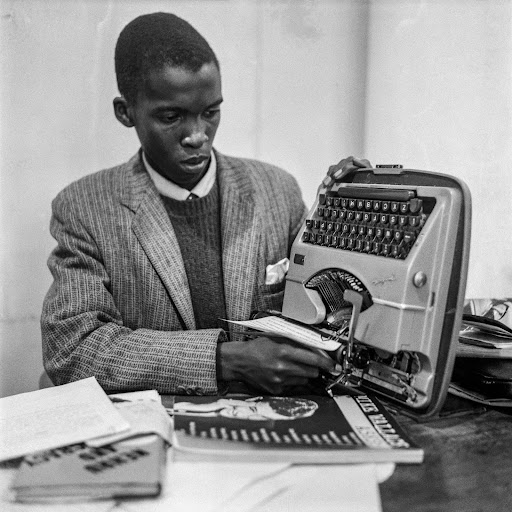

Lewis Nkosi at the Drum offices (BAHA/Africamediaonline)

“From early in my life I have viewed literature as a unique universe that has no internal divisions. I do not pigeon-hole it by race, or language or nation. It is an ideal cosmos coexisting with this crude one.” – Dambudzo Marechera, The African Writer’s Experience of European Literature

A majority of South African literary commentators and critics suffer an acute anxiety that disallows them the wisdom to sit still and listen, a condition one critic has characterised as the incapacity to shut up and leave the text alone. In our quest to be suspicious readers, let us be wide awake, and not fall into the trap of embracing and endorsing an impoverished type of reading that misses the fundamental function of criticism, which is to identify, indicate and intensify what the text says about itself.

On one side, there is the obsession with literary hagiography, a common practice in which certain individuals are written into our literary history in a language as politically pleasing and pristine as to erase or shield any limitations and inadequacies that require critical attention.

On the other side, there is deafening silence and deadening ignorance; the critic being treated with utter negligence for calling out the country’s creative and critical indolence. Once the critic has died, all kinds of homages, perspectives, reflections and questionable evaluations are expressed. In South African literature, Lewis Nkosi, the late novelist, critic, essayist and playwright is such a figure.

In his lifetime, Nkosi arguably saw little effort in terms of an earnest and intense engagement with his controversial critical inputs. I am particularly referring to his aesthetic assumptions of what constitutes literary value specifically in relation to Black writing. In South African literary culture, there is an unacknowledged reticence, resistance and even refusal to debate Nkosi’s politics and principles of aesthetics, or to think about their place in contemporary Black literary practices.

With the exception of Still Beating the Drum: Critical Perspectives on Lewis Nkosi (2006), Writing Home: Lewis Nkosi on South African Writing (2005; 2016), and the recent publication Lewis Nkosi. The Black Psychiatrist | Flying Home! Texts, Perspectives, Homage (2021), there is rarely a sustained — let alone a suspicious — reading and rereading of Nkosi’s work. There is neither a reading that advances Nkosi’s conception of aesthetics and principles of literary value, nor one that complexifies the discussion by contesting his fundamental aesthetic assumptions about what constitutes value in literature. To disclose how he got here requires the theoretical labour and critical rigour Nkosi advocated and was exiled for by the South African literary establishment.

In Lewis Nkosi. The Black Psychiatrist | Flying Home! conversations that interrogate Nkosi’s literary criticism and theoretical musings and what his critical contributions mean for Black authors writing today are not entertained nor hinted at. The volume does not present itself as a resource book, nor does it claim to provide original critical interventions on the work of Nkosi, either as a critic or as a playwright. In their introduction, the editors, Astrid Starck-Adler and Dag Henrichsen, confess that the idea for this volume started in 2016 when they gathered in a room to commemorate Nkosi’s 80th birthday in Basel.

Friends and colleagues were invited to join the commemoration and share stories, recollections, and experiences of their encounters with Nkosi. The editors do not, as one would anticipate, provide a contextualisation of this volume in relation to the previous critical interventions on the writings of Nkosi. They do not situate Nkosi within contemporary debates about Black aesthetics and the ethics that complement such designation. It is not at all surprising, then, to discover that what takes up much space in the volume are writings that are driven by this spirit of commemoration, conviviality and camaraderie. There is not much substantial and critical insight to glean for a serious scholar interested and invested in either discounting, or broadening, Nkosi’s ideas on the politics that inform the aesthetic framework in which his criticism of Black writing functioned, or the trajectory it followed.

This is definitely not a volume of critical and polemical writings, in the fault-finding fashion of Nkosi, the physical bearer of the offending word.

First, my assessment of Lewis Nkosi. The Black Psychiatrist | Flying Home!, which consists of 38 pieces and is partitioned into four parts, is guided by the book’s primary concern, which is to make available an essay, an interview and two plays that were previously inaccessible to the reading public.

Lewis Nkosi in his pre-exile days at Drum. (Photo: African Image Pipeline)

Lewis Nkosi in his pre-exile days at Drum. (Photo: African Image Pipeline)

Second, I could not help being curious whether or not the contributors are going to critically engage the primary texts by providing the readers with a compelling reading of the work outside the frame of journalistic platitudes marked by an attitude of ready-made praise-singing.

In the part titled “From the Desk of the Writer”, the reader is provided with the two primary texts, The Black Psychiatrist and Flying Home!. These two plays are both accompanied by contextual commentaries by Starck-Adler, a helpful gesture, especially for readers encountering the plays for the first time.

In the part titled “From the Desk of the Critic”, the previously unpublished essay, The World of Johan van Wyk, is grouped together in this section with an unseen interview of Nkosi conducted by journalist Tiisetso Makube. In the essay Listening to the Voices in the Streets and the Songs I Hear, Makube and Nkosi engage the difficulty of writing of place when one is distanced from the subject of discussion. Nkosi admits that it is indeed difficult to assess and form an opinion on the quality of literary inputs while he is not on the scene.

In the Van Wyk piece, Nkosi reads Man Bitch, an autobiofictional novel, whose sense of place and space allows Nkosi to render a reflective reading of the familiar yet strange Durban world painted by the pen of Van Wyk. Familiar, because, as Lindy Stiebel has observed in Letters to My Native Soil: Lewis Nkosi Writes Home, Nkosi, like the narrator of Man Bitch, has been “mugged and stolen from during his stays in this twilight zone behind the beachfront hotels”. One feels that there could not have been a better way of reading Man Bitch without satisfying the nostalgia the book seems to have aroused in Nkosi. Like Man Bitch, which fluctuates between fiction and autobiography, Nkosi’s reading oscillates between the autobiographical, historical, and critical registers without difficulty.

Ntongela Masilela’s excellent contribution reads Nkosi’s modernist conception of aesthetics together with that of HIE Dhlomo’s, which, after all, informed Nkosi’s literary practice. Masilela’s essay is superb and special. It is pastiche, a tribute to Nkosi’s style, specifically in his reflection on both the work and the encounter with the writer, as in the assessment in Nkosi’s essay Alex La Guma: The Man and His Work. In the latter, Nkosi reflects on his encounter with La Guma, before diving into his thoughts about the politics of the writer and the aesthetics of his work. Masilela uses the same framework in his essay titled HIE Dhlomo and Lewis Nkosi’s Historical Imagination, Or Meeting Lewis Nkosi in Warsaw in 1989.

Masilela narrates his encounter with Nkosi, the latter’s encounter with Dhlomo, before he asserts and exposes the dis/continuities in the politics and aesthetics of Dhlomo and Nkosi. He juxtaposes HIE Dhlomo’s conception of modernity with that of Nkosi’s in order to reveal the congruence, and the influence, of the former in the critical and creative aesthetic of the latter.

His concern is not only to show Nkosi as an apprentice of HIE Dhlomo, but to re-establish a link absent in most readings of his work, reading that rushes to link Nkosi with Black writers outside the country and continent, without acknowledging the South African flavoured aesthetic framework modelled on the modernist ideas of HIE Dhlomo.

This meditation on the modernist aesthetic approach of Nkosi’s thinking and writing style, both in his work and of those writers he assessed or appreciated is also considered by Cheela Chilala, whose essay, Facing Forward and Backward: Lewis Nkosi’s View of Modernism in African Literature, complements the central ideas of Masilela’s contribution. Chilala reads and reiterates Masilela’s point that Nkosi’s proposition of his modernist approach arises from drawing from both indigenous and foreign forms, as demonstrated by some instances Chilala references from Nkosi’s Tasks and Masks: Themes and Styles of African Literature.

The contributions in this volume are wide-ranging in their engagement with the oeuvre of Nkosi. Some revisit texts that were treated in the first full-length study on Nkosi. For example, in the essay titled Rereading Mating Birds, Lucy Graham revisits Mating Birds and there’s nothing radical or illuminating in her reading, especially if one has encountered her piece in Still Beating the Drum. Graham admits that her theoretical framework in the previous essay was not “quite developed”, so that in her rereading Graham attempts to reconsider Mating Birds in relation to the Freudian theorisation of mourning and melancholia via the interpretive lens of Judith Butler. In short, Graham’s contribution to this volume is merely an attempt to reread Mating Birds in order to improve what she retrospectively considers as a theoretically underdeveloped outline. What is outstanding in her piece, though, is the attached email exchange between Graham and Nkosi, specifically the polemical parts wherein Nkosi takes to task André Brink’s misreading and misinterpretation of Mating Birds.

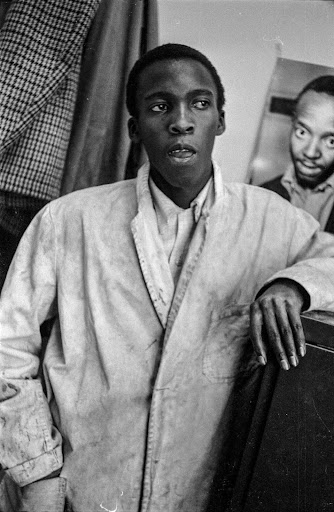

Portrait of the artist as a young man: Lewis Nkosi would have been disappointed with the parts of a new collection of essays that are obsequious and not academically rigorous, the reviewer says. (Photo: African Image Pipeline)

Portrait of the artist as a young man: Lewis Nkosi would have been disappointed with the parts of a new collection of essays that are obsequious and not academically rigorous, the reviewer says. (Photo: African Image Pipeline)

In her contribution, Clara Schumann renders a rare take on Mating Birds. She compares the power relations that shape the encounter between Ndi Sibiya and Veronica Slater in relation to the affairs underwriting the encounter of South African doctor and psychoanalyst Wulf Sachs and the healer and diviner John Chavafambira, documented in the genre-defying text Black Hamlet. Schumann’s symptomatic reading is that Nkosi’s Mating Birds, in an unconscious way, “is a postcolonial rewriting” and re-interpretation of Sachs’ Black Hamlet. One of her main points is that the power relations in both texts are shaped by the same colonial situation and share similar psychoanalytic impulses. Though Schumann’s comparative reading of Black Hamlet and Mating Birds is thought-provoking, it is not theoretically convincing. One cannot cease wondering what kind of assessment we would be reading had she decided to centralise the play The Black Psychiatrist in her comparative study. In addition, it appears to me unhelpful to discuss Black writing (in this case, Nkosi’s Mating Birds), psychoanalysis, and Black and white power relations in the colonial situation without a reference to Frantz Fanon, or his contemporary interlocutors.

In Nkosi, The Motherless Child, Litzi Lombardozzi takes us into Nkosi’s childhood and youth, with help from some of Nkosi’s texts, interviews, conversations, discussions, email exchanges, and Nkosi’s outline of his would-be memoir. Beyond the fleeting moments of surprising critical outburst on the definitions and dimensions of home and exile, on the devastating effects of deracination and dislocation, or the psycho-social ramifications, the text is unhelpful to a scholar interested in something beyond the biographical overview, which is the main preoccupation of the contribution. Perhaps a prescient scholar whose focus is to write the biography of Nkosi would be compelled to consult Lombardozzi’s contribution and couple it with her doctoral thesis Journeying Beyond Embo, specifically the chapter Embo and Beyond: A Biographical Sketch, to retrace and recreate Nkosi’s childhood and youth, encounters and experiences, in life and in literature.

Between Flying Home! and The Black Psychiatrist it is the latter play that receives some, albeit scant, critical attention. Only theatre director Deborah A Lutge’s intervention directly deals with a detailed process and the politics that informed the treatment and framework for the staging of The Black Psychiatrist, which she mounted at the Durban University of Technology’s Arthur Smith Hall in 2013. Though I find the contribution partially informative, I am unconvinced by the moves Lutge makes to corroborate the conceptual framework she terms “directorial ubuntuism”, which is as confounding as it sounds.

The idea of “directorial ubuntuism hinges on the following adage: I am because you, the artists and the audience, are you. It is a reductive and oversimplified engagement with the philosophy of ubuntu as theorised in the informed and enriched scholarship of Mogobe Ramose and Ndumiso Dladla. For Ramose, ubuntu is more than simply a concept or philosophical abstraction. Rather, “it is a lived and living philosophy of the Bantu-speaking peoples of Africa.”

So, according to Ramose, and in contrast to Lutge’s directorial method, ubuntu cannot be treated as “an ahistorical philosophy that may be turned into a thought experiment,” which is precisely what Lutge attempts to achieve. Soon the reader sees how the collective contributions suffer from a clear and concrete conceptualisation. For how can a volume that provides the reader with two powerful plays such as The Black Psychiatrist and Flying Home! have so little to say about the primary texts that ought to be the principal focus?

The last section of the volume, which includes “Poems, Letters, Conversations and Reminiscences” is the least engaging. It contains information that may probably be important for those interested in various writers narrating their encounters and experiences with Nkosi. A host of contributors are concerned with either narrating how they jived with Nkosi, or have once sat in the same room as the critic. Here, there is nothing for the students of polemics and literary pugilism.

There is nothing about Nkosi’s aesthetic anxiety. The section is overflowing with fragments, memories, notes, poems, anecdotes, and other writings that are mum on the actual work of Nkosi, but rather focus on meetings or moments with the man without using that as a jump-off point to discuss his ideas on literary aesthetics, as Masilela and Chilala do in this volume.

When Lindy Stiebel and Liz Gunner commissioned, compiled, edited and published Still Beating the Drum: Critical Perspectives on Lewis Nkosi, Andile Mngxitama wrote an assessment of the collection. In my reading of the last part of Lewis Nkosi. The Black Psychiatrist | Flying Home!, I cannot help but recall Mngxitama’s apt title, Star-struck Critics Succumb to Nkosi’s Wit, which seems to fit my evaluation of this volume, especially the last segment, which has the most contributions, yet whose authors are resistant to putting Nkosi’s ideas on trial.

Mngxitama, in his perceptive assessment of the overall level of engagement of the contributors in Still Beating the Drum, writes: “To do justice to Nkosi’s colossal contribution to literature and art will take an examination of his work by critics less susceptible to his charms and wit.

One can think of three such persons; Wole Soyinka, Es’kia Mphahlele and Don Mattera, fortunately all three are still alive. Incidentally all three may have one or two scores to settle with Nkosi, and their contributions could have hugely enriched this volume. One can only hope that they will in future collaborate on another project on Nkosi’s impressive collection of work.”

Robust engagement: Lewis Nkosi laughs with Mxolisi Mgxashe at the launch of his book, Mandela’s Ego in South Africa in 2006. (Photo: Denzil Maregele/ Foto24/ Gallo Images)

Robust engagement: Lewis Nkosi laughs with Mxolisi Mgxashe at the launch of his book, Mandela’s Ego in South Africa in 2006. (Photo: Denzil Maregele/ Foto24/ Gallo Images)

Unfortunately, such a dream proves impossible, since Mphahlele is no longer here. Mattera and Soyinka are either too old or preoccupied with other responsibilities. They do not seem up for the task. We would have to do the critical work ourselves, but not in the manner of the majority of the contributors in Starck-Adler and Henrichsen’s volume.

Now it is easy to see why the last and least critical section in the volume is teeming with writings whose authors not only, unashamedly and uncritically, succumb to Nkosi’s charms and wit, but are also intimidated and critically stunted by Nkosi, even in his death; even when he is no longer there to point out misreadings and misjudgments of his work, as he did with Brink.

One may even conclude that the majority of the contributors are lacking the critical and polemical spirit of Nkosi embodied in his notorious Fiction by Black South Africans — an essay included in Still Beating the Drum, which led Mngxitama, in his above-referenced evaluation, to ask uncomfortable, yet necessary questions that he found absent in the Drum volume.

The same case can be made about this recent publication. One imagines an unhappy and unconvinced Nkosi responding with scathing sarcasm. For what better and deeper way of honouring the literary legacy of Nkosi than being sharp in our engagements with his own work, and expose the cracks and crevices in his own thinking and writings, amid camaraderie and crass celebrations?

For Mngxitama, “any exciting start to any useful discussion of Nkosi’s critical writings is to put his take on Black literary aesthetics under the microscope”. This volume, like the previous one compiled and edited by Lindy Stiebel and Liz Gunner, has no intention to attend and tease out what Mngxitama called the “obvious tension” in the work of Nkosi. It is a tension which, according to Mngxitama, arises from “seeing and acknowledging the inherent value of a project located squarely on the promotion of Black antagonistic subjectivity and expression and on the other hand maintains fidelity to Eurocentric values as standard bearers when it comes to literature and art”.

Chris Wanjala’s contribution in Still Beating the Drum seems to have provoked Mngxitama to make such an assertion. It was Wanjala who wrote about Nkosi’s “intense relation to Western aesthetics”. Wanjala, in an essay titled Lewis Nkosi’s Early Literary Criticism, claims that Nkosi’s critical aesthetic principles and literary value rubric are “largely mapped by European societies”. Yet Wanjala is quick to add that it would be a mistake to assume that his critical interventions were a matter of “servile mimicry”. He suggests that his ideas should be taken “in the spirit of comparative studies”. Wanjala, like Chilala, is aware of this enduring tension in the criticism of Nkosi, but does not in any way conclude that Nkosi is a “conscript of Euro-modernity”, an accusation also levelled at his contemporaries, such as Marechera and Ayi Kweyi Armah. Mngxitama, though aware of the “intense relation” does not provide enough textual work to corroborate his claim that Nkosi “maintains fidelity to Eurocentric values as standard bearers when it comes to literature and art”.

Similarly, Njabulo Zwane, in his recent article “Lewis Nkosi and All the Things We Could Be by Now if We Were Free”, published in the Mail & Guardian, reads and reduces Nkosi to a Eurocentric sycophant without any theoretical labour to corroborate the claim. He does not reference Wanjala or Mngxitama, but speaks about certain circles in which Nkosi has been labelled a reactionary Eurocentrist. There are many problematic assertions and limitations in Zwane’s reading, especially wherein he tries to bring in Chabani Manganyi’s critical observations and Frantz Fanon’s psychiatric writings in order to provide a reading of The Black Psychiatrist, that we, unfortunately, never actually experience. But dissecting or deconstructing plays like The Black Psychiatrist or the sequel Flying Home! demands much more than repeating the playwright’s literary intentionality. One is compelled to remind Zwane that it is not enough to summarise what is occurring in a play or being argued for in an essay without providing one’s own critical input. In dealing with the plays, context and criticality are key, for Nkosi was not writing a dramatisation of any conceivable Fanonian experience.

Zwane is misguided to claim that Nkosi had tendencies of a Eurocentric sycophant, or that Nkosi’s misjudgment of the sound and singing style of Abbey Lincoln is proof of Nkosi’s “conscription to Euro-modernity”. Zwane seems to have forgotten that faith — as embodied by his “I believe” in relation to his insistence on Nkosi being a “conscript of Euro-modernity” — has no place in matters of rigorous reading and critical writing. It is the latter that compels me to engage the obvious tension in Nkosi’s criticism. It forces me to attend to Zwane’s simplistic reading that has him unquestioningly accepting and labelling Nkosi “a conscript of Euro-modernity”.

In his lifetime, Nkosi saw little earnest and intense engagement with his controversial critical inputs, argues Unathi Slasha. (Photo: www.baslerafrika.ch)

In his lifetime, Nkosi saw little earnest and intense engagement with his controversial critical inputs, argues Unathi Slasha. (Photo: www.baslerafrika.ch)

One cannot, in any leap of logic, mistake a misjudgment for reactionary Eurocentricity. If we follow Zwane’s logic we would be compelled to use the same terms to dismiss HIE Dhlomo for his hostility to jazz. This would be a sign or symptom of simplistic reading, because Dhlomo, like the rest of the New African Movement intellectuals, was also caught in this obvious tension, or what Ntongela Masilela terms the drama of modernity, in which, according to Nkosi, “the modernist movement in Africa faces both ways at once”. Moreover, it is incorrect that Nkosi’s “victims” were strictly Black, when he has equally engaged white writers such as Nadine Gordimer, JM Coetzee, Herman Charles Bosman, Athol Fugard, Brink and Alan Paton, bringing to light what worked in their literary works and what did not. One is appalled that it is not enough to pull out a copy of Tasks and Masks to dispel this distortion, for in that book the critic covers a wide range of writers from different backgrounds, including African, British, US, and European. In Nkosi’s mind, like that of his contemporary Marechera, writers occupy a single country, an “ideal cosmos” where all literary works are held in equal critical measure and treatment in ways that undermined and trudged beyond the apartheid-erected and established borders of culture.

Wanjala does not conclude that Nkosi is a Eurocentrist, though he entertains the tension or intense relation in his work. It is confounding that critics and commentators, like Wanjala and Mngxitama, among others, who have identified this drama of modernity, this intense relation, or obvious tension, insist on emphasising Nkosi’s reliance on Western aesthetics, or Eurocentric values, and proceed to support this statement by mentioning Nkosi’s reference to Franz Kafka, Fyodor Dostoevsky and James Joyce, yet leave out the part in which, in the same essay, Fiction by Black South Africans, Nkosi celebrates the writings of Amos Tutuola or Chinua Achebe as excellent examples of an African modernist aesthetic. It would be helpful if Wanjala, Mngxitama, and now Zwane, were to tease out and delineate these Eurocentric value rubrics. Unlike Wanjala and Mngxitama, Zwane does not bother to entertain and engage the gradations of the said “intense relation”. He is simply confident to conclude without any substantial evidence, by-passing the process of critical examination.

What ought to complicate the matter to any serious reader is Nkosi’s equal appreciation of excellent literary works both in the Western and African world. This, more than anything, depicts what Nkosi’s friend and contemporary Marechera has termed the need for writers to occupy their own country, continent, and “cosmos”. It would be unintelligent to think Nkosi was not aware and did not acknowledge this obvious tension or intense relation. For he acknowledges the paradox and claims that what we mostly know as African modernism is built on the back of European models. He also acknowledges that Western modernism has been enriched and keeps enriching itself by appropriating and adopting influences from African cultural and religious practises. Here is Nkosi, in an interview with Stephan Meyer, responding to a question about the role of Black culture in modernity: “African practices have had an impact on the development of literary styles in South America such as magic realism. Once again the paradox here is that whatever enriches or invigorates Western modernism from Africa is not some modern version of itself but influences that emanate from what are dismissed by modern Africans as moribund tradition. What passes as African modernism is in fact constructed almost entirely out of European models.” Mngxitama and Zwane seem to me unaware or unconvinced that it is this “obvious tension” — the balance between two opposing traditions — that gives Nkosi’s literary aesthetic approach its structure and style, its cohesiveness and coherence.

In South African Literature: Resistance and the Crisis of Representation, Nkosi’s stance on what has come to be called protest writing is complexified in such a way that it becomes clear that his position cannot be reduced to matters of simple technical competency. Rather, at stake is the question of what African indigenous forms can produce through the encounter and appropriation of European-derived forms of expression like the novel. Nkosi refused to join the chorus of those African critics and commentators who ganged up and criticised and condemned Tutuola for his “broken English”. Instead, he critically considered The Palm-Wine Drinkard alongside texts like Ulysses as examples of imaginative and experimental texts that aggressively assaulted English linguistic propriety while producing something entirely inventive. In other words, for Nkosi, Tutuola is an example of an African writer exploiting this drama of modernity, for Tutuola’s work “faces forward to the latest innovations in fiction as well as backward to the roots of African tradition”.

The problem with Lewis Nkosi. The Black Psychiatrist| Flying Home! is not Zwane’s grievance that Nkosi’s “own writings only make up a third of this collection’s page count”, as he complains in his rather random and roaming reflection that bursts with oversimplifications and generalisations. The problem is the inadequate critical and scholarly engagement performed on the newly available texts, which have not been previously published and made accessible to the reading public, except through staging in various places and platforms around the world, on the continent and in Nkosi’s birth country. For example, unlike The Black Psychiatrist, the sequel Flying Home! has never been staged nor made available to the reading public. And yet, even in this volume, Flying Home! is not given any critical consideration. It is unfair to the editors for Zwane to expect out-of-print essays in a volume intended to avail rare texts and explore a creative side of Nkosi that has received little critical reflection. It is unfair to the readers for the editors and the majority of the contributors to resist performing the fundamental function of criticism on the newly available writings of Nkosi.

Zwane’s reasons for Nkosi’s exile from the South African literary world are contradictory. First, he claims that Nkosi’s “alienation from the Black public sphere” was caused by what he describes as “internal aggression” against fellow Black writers, coupled with the “whiteness of the discourse on his work”. Elsewhere he asserts that it is due to Nkosi’s “worldliness in the context of the provincialism of much of the discourse known as ‘South African studies’ that made him a thorn in the sides of not only the Afrikaans-speaking verkrampte types, but also the English-speaking liberals and many Black radicals too”.

The first statement seems to suggest that Nkosi’s exile from the literary landscape was mainly because he was too critical of the writings of his Black contemporaries. The second statement is true about Nkosi who preferred to call his “alienation” from the philistine literary establishment exile, for he pronounced a disagreeing discourse in a climate that refused to accommodate and endorse a persistent critical culture. Zwane seems to suggest that Nkosi the critic should have shown more leniency in dealing with the work of his Black contemporaries. Zwane seems to have forgotten that Nkosi was often annoyed by the unintelligent dismissal of any discussion of theory, as was the case with the writer Mothobi Mutloatse, whom Nkosi lambasted for the said reason.

Zwane appears unaware that it is the impoverished state of our literary culture, a culture that is historically hostile to literary theory and autocriticism, that allows vociferous voices, like that of Nkosi and others, to remain ignored and unheeded because they interrogate the easily accepted literary value systems that have been inherited and held as standards and remain unquestioned.

What is more inexcusable is how Zwane eagerly accepts the influence of James Baldwin on Nkosi, yet ignores that Nkosi’s treatment of certain Black South African texts in Fiction by Black South Africans was not a matter of Eurocentric obsequiousness, or because he was a “conscript of Euro-modernity”, but insight and critical attitude motivated and modelled on Baldwin’s moves in his seminal Everybody’s Protest Novel.

According to Njabulo Zwane, Nkosi’s ‘wordliness […] made him a thorn in the sides of Afrikaans-speaking verkrampte types, English-speaking liberals and many Black radicals’. (Photo: Ullstein Bild/Getty Images)

According to Njabulo Zwane, Nkosi’s ‘wordliness […] made him a thorn in the sides of Afrikaans-speaking verkrampte types, English-speaking liberals and many Black radicals’. (Photo: Ullstein Bild/Getty Images)While it is true that Nkosi’s influences are extensive, his conception of modernist literary aesthetics refuses to be restricted to his sharing with Baldwin the “worldliness which came from reading of the classics of Western canon”. As Masilela shows in his insightful chapter, HIE Dhlomo and Lewis Nkosi’s Historical Imagination, it is indispensable to juxtapose in order to expose the influence, and therefore congruence, in the vision and practice of Dhlomo and Nkosi. Dhlomo, in Why Study Tribal Dramatic Forms?, had already established an aesthetic appreciation and proposed a poetics of art that arises from the obvious tension or intense relation between the indigenous cultural practises and the influences of foreign forms.

It is no wonder, then, that in Fiction by Black South Africans Nkosi would praise Tutuola and Achebe, alongside Dostoevsky and Joyce, while he criticised the type of writing he saw as being hostile to tradition, indigenous or foreign, a writing that was not inventive, a writing that could not exploit the intense relation, the obvious tension, in the words of HIE Dhlomo, “to combine the alien, the tradition and the foreign, into something new and beautiful”. This is one of the apparent principles in Nkosi’s aesthetic approach that he inherited from Dhlomo’s conception of cultural modernity.

To maintain an uncritical position such as Zwane’s is to bury alive the work of Masilela, who has, over the years, sought to locate Nkosi’s writings within what Masilela laboriously theorised as The New African Movement, a South African-started modernist movement that stretched from the 1800s to 1960s. Indeed, Zwane is correct to claim that there is, in the current literary circles, “a room for a kind of decontextualised reading that dominates the discourse on Nkosi’s oeuvre”. Zwane’s recent piece is the epitome of this type of decontextualised reading, which is the worst way of disrespecting the dead and distorting their ideas.