Lewis Nkosi with Dambudzo Marechera at a writers’ conference in Harare in 1983. (Photo: Tessa Colvin)

For me, writing is primarily a struggle with language; words refusing to be made ‘flesh’.

Lewis Nkosi, How I Write

“For me, writing is primarily a struggle with language; words refusing to be made ‘flesh’.” — Lewis Nkosi, How I Write

‘Home is where the hatred is’

In our conversation about the political economist Morley Nkosi’s study of the development of South Africa’s labour structure, Black Workers White Supervisors, a colleague recently asked me which subject I thought deserved a similar tome-length treatment and I almost immediately replied, “A history of the mental asylum’s role in the advancement of this country’s colonisation.”

The import of such a study was impressed upon me during my student days, not so long ago, in the quaint university town of Makhanda — which is also where the Eastern Cape’s oldest mental institution, Fort England Psychiatric Hospital, is located. As suggested by the name, this hospital’s buildings initially functioned as the British colonial government’s military barracks, before they were “converted” for their current purpose.

Frantz Fanon’s psychiatric writings argue that colonial social relations are the key to understanding Black people’s historical sense of a lost or absent identity, which in turn determines the form of mental illnesses among the people. To demonstrate this point, let’s take an observation by Chabani Manganyi — South Africa’s first Black clinical psychologist, based at Soweto’s Baragwanath Hospital during the late 1960s to early ’70s — that his “working-class Black patients suffered from psychological disturbances presenting as physical illnesses”.

Following Fanon’s “sociogenic principle”, we can map the road of these patients’ recovery along South Africa’s history of master-slave relations between its “black workers and white supervisors”; a road that passes through Fort England, where “Black patients were involved in manual labour … under ‘the guise of occupational therapy.’”

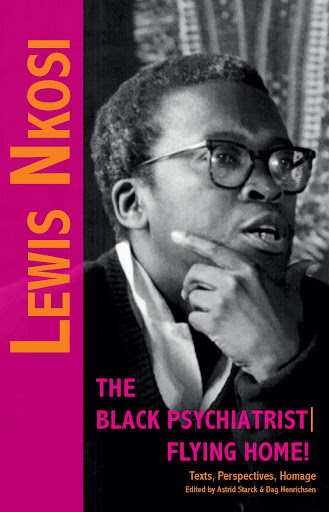

I thought about this dark history of psychiatry when the edited volume titled Lewis Nkosi. The Black Psychiatrist | Flying Home: Texts, Perspectives, Homage (Basler Afrika Bibliographien) crash-landed on my desk. This 444-page book collects the South African-born-but-exiled writer and critic’s two plays, an essay and an interview, both of which didn’t see the light of day until now, as well as a whole host of reflections on and tributes to Lewis Nkosi. Given that there are two other edited collections of Nkosi’s critical writings on South African literature and culture (namely, the Still Beating the Drum and Writing Home edited volumes, published in 2005 and 2016, respectively), one couldn’t help but feel hoodwinked by the fact that Nkosi’s own writings make up only a third of this collection’s page count.

Nkosi’s writings make up only one third of this new tome, which is edited by Astrid Starck-Adler and Dag Henrichsen and published by Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

Nkosi’s writings make up only one third of this new tome, which is edited by Astrid Starck-Adler and Dag Henrichsen and published by Basler Afrika Bibliographien.

I’m no literary scholar, but given Nkosi’s stature in the recent history of African letters, the omission of his key out-of-print essays in a volume that is supposedly “intended as a reader” can only be read as an act of editorial negligence. More so if we consider the fact that one of this volume’s editors, Nkosi’s Swiss-based partner, Astrid Starck-Adler, holds the copyright to all Nkosi’s writings.

This raises a whole range of not-so-unrelated questions about the location and ownership of Africa’s creative intellectual property (including, but not limited to, written documents, musical recordings and visual art), which invariably determines who can legitimately speak to this work. Therefore, it is not surprising that the scholarly discourse on Nkosi is, to a large extent, dominated by White women.

Anyway, the focus of this volume is ostensibly on Nkosi the playwright. But, again, everybody knows that it was through the essay that Nkosi was able to make his greatest artistic contribution — which was to fashion a tsotsi-styled critique of anti-colonial aesthetics in mostly the fictional writing coming from the land of his birth. This critique was as Okapi-sharp as it was mad fly.

But just like the Msomi and Spoilers gangs that animated the pages of Drum magazine, where he practised his journalism in the 1950s, the “victims” of Nkosi’s pen were his fellow Black writers. This “internal aggression”, together with the Whiteness of the discourse on his work, has led to Nkosi’s alienation from the Black public sphere, which has severely weakened the state of this country’s public discourse.

Future Black readers would do well to remember Nkosi’s sustained engagements with the Afro-diasporic world of Black letters. It would be against this world’s protocols of reading to talk of Nkosi’s tsotsi-like critique without talking about the fabulous James Baldwin. Bringing this point home is writer and filmmaker Bra Bongani Madondo’s inclusion of Nkosi’s latter-day essay titled To the Mountain: Looking for Jimmy Baldwin in his 2016 collection of essays, lyrical elegies and dreams, Sigh, the Beloved Country.

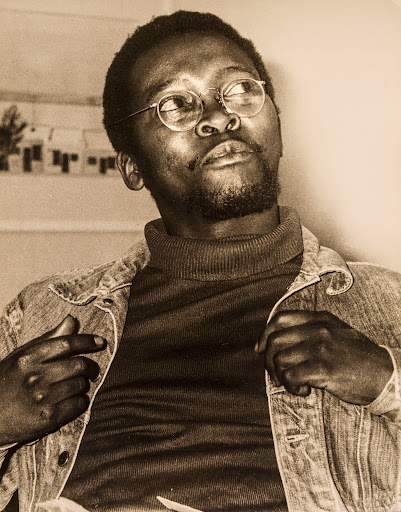

Nkosi’s decision to go into exile was deeply informed by his refusal of the place that colonial-apartheid society had set aside for Black men like him. (Photo: Jan Stegeman)

Nkosi’s decision to go into exile was deeply informed by his refusal of the place that colonial-apartheid society had set aside for Black men like him. (Photo: Jan Stegeman)

Describing his first textual encounter with Baldwin, Nkosi talks of his familiarity with the social world of Baldwin’s first novel, Go Tell It on the Mountain, because “of all the places in Africa, South Africa resembled America the most in the intensity of its racial conflict.” As well as their shared experience of a systemic criminalisation of their respective existences as Black writers, which led both to flee their native lands, these two kindred spirits also shared what Nkosi described as Baldwin’s “worldliness, which came from reading the classics of the Western canon”.

I want to argue that it is Nkosi’s worldliness in the context of the provincialism of much of the discourse known as “South African studies” that made him a thorn in the sides of not only the Afrikaans-speaking verkrampte types, but also the English-speaking liberals and many Black radicals too.

During the 1950s, while the National Party sought to Balkanise the country, Nkosi argued for “an integrated view of our culture”. This can easily be read in liberal terms, and perhaps the twenty-something-year-old Nkosi was a liberal. In his discussion of Nkosi’s first play, The Rhythm of Violence, Sikhumbuzo Mngadi writes that it “offers no significant advance from … the idea of liberal reform and of English-speaking White liberal trusteeship”.

However, the same cannot be said about the more mature Nkosi who wrote the two plays headlining the volume under discussion. With The Black Psychiatrist and Flying Home, Nkosi stages a critique of Western civilisation in South Africa.

At the heart of the two plays is a quarrel about whose history and memory counts. The white South African expatriate, Gloria Gresham, comes to the London offices of Dr Dan Kerry, a Black psychiatrist also from South Africa, to confront him about their past love life. While accusing Kerry of wanting to forget about his past (which, as per the racist ideology, is only reducible to his sexuality), Gresham also does not want to accept the political, economic and sexual violence committed by her father in his pursuit for dominance over the land and its people.

By loosely basing Kerry’s character on the life and work of Fanon, Nkosi was able to stage a critique of the official-colonial narrative of “sanctimonious white South Africans” (to pilfer from Sol Plaatje); thereby, unmasking the libidinal economy of this country.

‘The right to love refusal is black music’

The imperative to counter the wilful amnesia of the Gloria Greshams of this world necessitated the historical detour at the beginning of this piece. This detour was also taken to give a sense of place to the text. The “bad faith of some of our supporters in the social struggle for equality”, which Nkosi was so critical of in the post-1994 period has created room for a kind of decontextualised reading to dominate the discourse on his oeuvre. This strictly textual approach ignores the fact that place — and its musicality, in particular — “is a major life force inscribed in his work”, according to Nkosi’s dear friend and literary agent, Bra Sandile Ngidi.

Lewis Nkosi dancing with Zukiswa Wanner in Cape Town. Nkosi took the spirit of refusal at the heart of jazz and mbaqanga with him to exile, writes Zwane. (Photo: Siphiwo Mahala)

Lewis Nkosi dancing with Zukiswa Wanner in Cape Town. Nkosi took the spirit of refusal at the heart of jazz and mbaqanga with him to exile, writes Zwane. (Photo: Siphiwo Mahala)

Nkosi’s decision to go into exile was deeply informed by his refusal of the place that colonial-apartheid society had set aside for Black men like him. At the heart of this refusal was the democratic spirit of the urban musics of jazz and mbaqanga, which facilitated a kind of failed experiment in non-racialism among the artists and students who frequented the shebeens of Johannesburg. Nkosi took this spirit of refusal (which is to say, this music) with him when he went to take up his Nieman Fellowship at Harvard University in December 1960.

On arrival in the US, Nkosi spent a few months in New York, where he immersed himself in the city’s lively jazz scene. He wrote two essays about his encounter with New York — both collected in Home and Exile, which was published in 1965. It is the second of these essays to which I want to briefly bring the reader’s attention, because it is in this essay where I believe Nkosi’s conscription to Euro-modernity is tragically exposed.

Styled as a review of the then-new music by Abbey Lincoln and her working band of 1961 (which included some of the baddest cats this side of the Milky Way), Encounter with New York, Part Two takes to task Lincoln’s unusual style of singing, which incorporated screams, for basically being bad art. Sounds a lot like his assessment of his peers’ fiction, right? Re-reading this hatchet job now, it sounds much like some of Stanley Crouch’s criticism of so-called free jazz, which is associated with the belief that “the jazz artist’s deepest transgression is to transform a binding instrument into a free voice”.

In response to her critics, Abbey had this to say: “Well, I heard Billie Holiday when I was 14, on a Victrola [a type of record player] in the country where I was living. She was always a great influence on my life. She was social. And she didn’t try to prove that she had a great instrument. This is not the form for people who use that approach. That’s the European classical tradition. We have voices.”

This did not dawn on the 25-year-old Nkosi, who, as we said earlier, can be described as a Black liberal during this time. But if Ngidi’s reading of an insistence on Black power informed by Nkosi’s belief that “music is resistance” in Mating Birds (1983) is to be believed, it would seem that Nkosi had a change of heart. At least where the music is concerned.

Nkosi’s worldliness in the context of the provincialism of “South African studies” made him a thorn in the sides of verkrampte types, English-speaking liberals and Black radicals alike. (Photo: Peter Schnetz)

Nkosi’s worldliness in the context of the provincialism of “South African studies” made him a thorn in the sides of verkrampte types, English-speaking liberals and Black radicals alike. (Photo: Peter Schnetz)

Much has been said about Nkosi’s position in the Great Debate about Negritude. Many Africanist critics have found it to be problematic, to the extent that it is not unusual to hear that Nkosi was a “reactionary Eurocentric” in some circles. I won’t say much on this debate, suffice to say that the above-mentioned essay allows us to see Nkosi’s Eurocentricity more clearly as an instantiation of Black classicism — in the tradition of Ralph Ellison, Albert Murray and Toni Morrison. Against the grain of the provincialism abounding in South African literary criticism, I have tried to locate Nkosi in the Afro-diasporic soundworld of Black improvisational music (or jazz).

The title of this piece refers to a Charles Mingus song, All the Things You Could Be by Now if Sigmund Freud’s Wife Was Your Mother, the meaning of which is nothing, according to Mingus. Nothing is what Gresham is ultimately willing to give up for the purposes of reconciliation.

Going forward, perhaps it will be more useful to read Nkosi’s misgivings about the notion of a peaceful state of African nature, which can be returned to, within the growing discourse about the Black subject’s dislocation in modern civil society; where “flying home” is foreclosed by naked white power.