Johannes Phokela’s mimicry of classical Western painting demands time to be convincing, an example being Ides of March (2015)

As we finish a walkabout of his exhibition, Only the Sun in the Sky Knows How I Feel: A Lucid Dream, at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art (Mocaa), Johannes Phokela urges me to return a few days later. He is finishing two more paintings (part of a triptych) in a makeshift studio in Cape Town (he is based in Johannesburg).

During our stroll through his exhibition, he keeps referencing absent works he has yet to complete. They are mostly other versions of the two classical leitmotifs from the history of Western painting that he keeps reinterpreting; The Execution of Emperor Maximilian is a series of paintings by Manet, which he re-reads through Goya’s Third of May and The Fall of the Damned, a religious scene interpreted by a stream of classical painters from Rubens to Bruegel.

It is perhaps unusual for an artist to continue working on paintings for a museum show that has already opened, but this isn’t an uncommon situation with Phokela. During several studio visits over the years, he has spoken at length about the wet paintings that don’t make the exhibition. It is probably one of his quirks, but it also evinces how immersed he is in an ongoing dialogue with the history of art. The ‘fall of the damned’ motif, which informs four works in this exhibition is one he has been fixated with since 1993 when he painted a replica of the titular Rubens work after an acid attack on it in the late fifties. Back then he was interested in artworks which had been defaced. This unusual interest culminated in the work titled Original Sin – Fall of the Damned as Damaged (1993), which featured on his graduation show in that year. This seminal work, which is part of the Scheryn collection, forms part of this exhibition. He intended on ‘attacking’ one of his own paintings of this motif – as a counterpoint. No doubt it will eventually surface at one of his next exhibitions. He can’t stop.

Scramble for Mars (2015)

Scramble for Mars (2015)

This makes it all the more tragic to learn that an injury to the nerves in his arm in a serious car accident forced him to take a long break from painting. He hasn’t been selling his art for five years, he says. The gallery that represented him — Gallery Art on Paper — closed.

He has, throughout his career, flitted from gallery to gallery. You sense he eschews the local art gallery system. Why else would he, along with others, open the Sosesame Gallery in Melville, Johannesburg, in 2016? Unfortunately it didn’t last. This quasi survey show at the Zeitz Mocaa is oddly conceived as a vehicle for Phokela to sell works.

“I wanted 90% of the show to be new works so I can earn some money,” he says.

In the end, about 50% of the artworks on exhibit are new paintings. The prices of the works don’t appear on the labels — just the name of the gallery that has agreed to sell them. This unconventional approach to an exhibition is in line with the museum’s own struggle to survive.

“We lost almost 90% of our funding during lockdown,” observes Storm Jansen van Rensburg, a senior curator. This has compelled creative solutions to new programming, and rethinking what the role of a museum might be, particularly during a pandemic. It is also not so unusual in the local art scene for dealers to offer museum curators works, knowing that the “museum cachet” will add value and seal a sale.

Flight of Europia (2015)

Flight of Europia (2015)

Phokela is not your typical struggling artist. He holds a masters in art from the Royal College of Art in London and, on returning to South Africa in 2006 after a long spell in the United Kingdom, he was received with open arms. He enjoyed a retrospective of sorts at the Standard Bank Gallery in 2009 and his work was selected for the South African pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2013.

Yet commercial success appears to have escaped him. His works come up at auction from time to time and either sell for low sums or not at all. Yet he is undoubtedly one of the country’s best painters — his technique, the scale of his works, the visual, sociopolitical depth present in his art all neatly situate him as such.

Will this Zeitz Mocaa show put him back on the map again? That the Goodman Gallery is selling the works showing at this museum exhibition bodes well for this outcome. That so many of the works are still in progress serves as a reminder that Phokela can’t churn art out, as so many Instragram-famous painters are seemingly able to do.

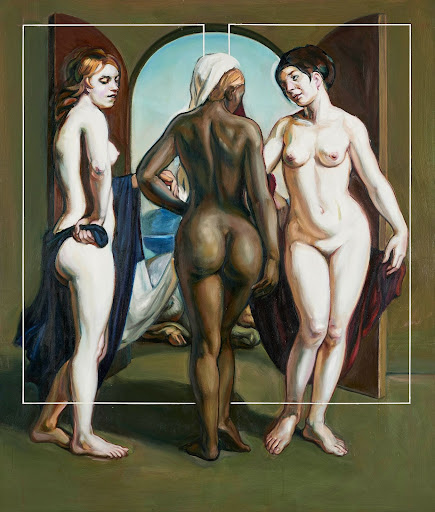

His paintings take time to make. His mimicry of classical Western painting demands time to be convincing. His art is multilayered. His paintings are not copies of classics; he reads paintings through other paintings, which are then filtered through present day events and popular culture.

After a hiatus due to injury, Johannes Phokela has started painting. (Courtesy of Zeitz Mocaa)

After a hiatus due to injury, Johannes Phokela has started painting. (Courtesy of Zeitz Mocaa)

As hinted at earlier his paintings are not “copies” of classics; he reads paintings through other paintings, which are then filtered through present day events, popular culture and anecdotal occurrences in his own life. When I ask him about the significance of the egg motif in his new paintings he explains that eggs kept appearing in unexpected ways in his life. A friend who confessed he was selling eggs – laid by quails. A fan in his building who left a tray of organic eggs as an anonymous gift to him.

His latest reinterpretation of The Fall of the Damned motif is inspired by events surrounding the coronavirus, according to Phokela. Titled Original Sin (Inner Circle), it presents naked, often pregnant women scrambling to avoid falling into the pit of hell that lies below.

“I made it during the middle of the lockdown during the third wave. I was aware that the virus was killing diabetics. I read somewhere about the link between diabetics and the sugar in powdered formula milk. It got me thinking about the sugar industry,” says Phokela.

You could also detect a racialised or gendered narrative in this grand work; the central figure at the top of the painting appears to be a pregnant black woman pointing at a seated white male figure. Is it a #metoo situation refracted through the lens of colonial/apartheid history? I don’t get the chance to quiz Phokela on this layer to the painting – there are too many new works to discuss and I get the impression that he might draw attention to different elements in a painting depending on the day. There are so many layers to unpeel.

Works in progress in Johannes Phokela’s Johannesburg studio. (Courtesy of Zeitz Mocaa)

Works in progress in Johannes Phokela’s Johannesburg studio. (Courtesy of Zeitz Mocaa)The image’s reference to the Christian notion of the original sin — consuming the apple, which led to the downfall of humankind — appeared to coincide well with Phokela’s interest in tackling the ills of the sugar industry. An Italian phrase featured at the bottom of the artwork can be loosely translated to read: “Sticky candy apple besieged by melting ice-cream.” In other words, the hell into which these subjects are being sucked into is one lined with desserts, a sugared excess, temptations they cannot resist.

Our diets, consumption and the politics of food is a dominant thread that weaves throughout his practice and this exhibition. It surfaces in older works such as Exciting Recipes (2015), which juxtaposes two South African traditions — a braai and the slaughter of an animal. Recent works pivot on food, too, such as Porch Resolution and Cult of Reason, which depicts a baboon with its paw caught inside a pumpkin (apparently this is how some farmers trap them). As the latter works suggest, hunger or greed is a trap that can, as in Original Sin, lead to a downfall. With books by Nietzsche, Marx and Darwin lined up near the baboon, you get the impression that reason can’t trump desire, or an appetite. Ideologies can perhaps only justify, explain, regulate or disguise these innate human qualities.

What is perhaps most interesting about Phokela’s practice is the manner in which he paints images that are not part of the European canon but appear to be, because of his classical style. This is the trick he plays on viewers. He is gradually rewriting our conception of the western art canon. Allowing it to cannabilse itself. A prime example of this is South Pacific Seascape (2009), which bears the text from the title of a story that caught Phokela’s attention — “Eating people isn’t always wrong”.

Cult of Reason (2021)

Cult of Reason (2021)

The story centred on misconceptions about cannibalism. Phokela was interested in how this myth about Africans was perpetuated by Europeans. The oil rig in the background of the painting makes a clear link between imperialism and neocolonial exploitation of natural resources that continues to the present day.

In this way he not only replays historical mythology but shows how our society appears to be caught in a never-ending loop. Greed might well be the grist for this destructive power-hungry mill.

This exhibition will hopefully compel a new cycle in Phokela’s professional career, renewed interest, lots of sales and another exhibition. For surely all those unfinished works he has in his studio that were destined for this one need to resurface.

Only the Sun in the Sky Knows How I Feel: A Lucid Dream is on show at the Zeitz Mocaa until 29 May 2022