The Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa. Photo supplied

This year solidifies five years of the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa as a beacon for African art shining from the centre of Cape Town’s Silo District. But the building has a history dating back to the 1920s, when it was the tallest building in Southern Africa.

This building, once known as the Grain Silo and Cape Town Grain Elevator, carries the history of a place, as well as untold stories of the people who built it and worked inside its walls. The redesigned building that now houses Zeitz MOCAA and the Silo Hotel tells stories of the economics of grain, sociopolitical hierarchies and architectural genius.

1924: South Africa’s tallest building

As its name suggests, the Grain Silo stored grain for export. Previously grain was transported in sacks by ox wagons to railway stations where it was stored under corrugated iron, which would lead to contamination. This led the government to identify better storage standards and regulations for grain.

As a project of the 20th century, the socio-political context of the Grain Silos’ construction carries a dark history. It was under the policies that developed a white minority, racial segregation and labour division.

“The silos are a sign of economic growth to some but oppression to others. It represented the political and socioeconomic power of the Afrikaner state,” as heard on the Zeitz MOCAA Architectural Tour.

The original Grain Silo was built by labour from Breakwater Prison, established in 1860. Today, the former prison is a University of Cape Town (UCT) campus and a hotel. The close proximity to the construction site across Clocktower Bridge meant those who were imprisoned did not have to travel far.

The original Grain Silo completed in 1924 was once the tallest building in South Africa. Photo supplied.

The original Grain Silo completed in 1924 was once the tallest building in South Africa. Photo supplied.

Breakwater Prison imprisoned Khoi Khoi, San and Xhosa people who were convicted under colonial era laws. The imprisoned nations were criminalised based on the system that governed their land occupation and movement across colonial geographical borders. These were the invisible workers whose hands were responsible for the building.

“Record of this labour is often not visible to the public, but the building remains as evidence of their existence,” says Zeitz MOCAA.

During the early 20th century, the area of the Victoria & Albert (V&A) Waterfront was surrounded by settlements where black labourers lived, but were eventually removed when the buildings were completed. Breakwater Prison was converted into a hostel where black dock workers lived from 1926 to 1989.

When construction was completed in 1924, the Grain Silo was the tallest building in South Africa, according to industrial archeologist David Worth. It is now a protected heritage site.

1935-1995: Icon by design

The Grain Silo consists of four main parts: the 42 tube silos, known as the storage annex, the taller tower-like working house, track shed that housed grain brought into the area, and the dust house outside.

The 57m tall working house served a multitude of functions. It received grain from carts on the track shed, lifted it to the top of the building by the use of elevators and provided facilities for grain to be weighed, cleaned, bagged, stored and distributed.

Construction on the The Grain Silo in 2014. Photo supplied.

Construction on the The Grain Silo in 2014. Photo supplied.

Little is known about what happened on the site between the 1930s and the 1950s, according to Worth. It is known that, by 1935, a prefab structure was built on top of the silos — the storage annex — as a lookout for the port captain. But it is not clear whether the silos had any strategic use during World War II.

“In the 1980s the lookout station on top of the storage annex was regarded as a strategic asset and kept in service as a backup lookout station for the port captain in the event of ‘terrorist’ attack on the Lourens Muller Building,” explains Worth.

In 1995, the last export shipment from the elevator was loaded in July because of a lengthy drought and high railage costs from the maize producing areas.

Brutalist design aesthetics

Upon first glance, the silo presents its rough, industrial concrete aesthetics. It’s a typical design of the Brutalist architectural style, most known for raw, exposed, concrete. Brutalist architecture often displayed massive forms, weight, and scale with an emphasis on exposed materials and displayed structures such as pipes, bolts and steel.

Although the Brutalist movement only emerged during the 1950s, the Grain Silo exhibits the characteristics of the designs. Its form is closely defined by its function.

The Grain Silo was an example of South African innovation. A local contractor was employed to construct the intricate elevator system. The building was one of the first major construction projects for Cape Portland Cement, making it a landmark in the history of the Pretoria Portland Cement Company, known today as PPC, according to Worth.

“This is a tough, raw structure that isn’t going to evaporate. It’s here for the long term,” says Thomas Heatherwick, whose studio, Heatherwick Studio, was tasked to reimagine the building for Zeitz MOCAA.

2017: A 21st Century Museum

According to a 2001 archeological report, the Conservation Plan for Cape Town Grain Elevator, the goal was to create and maintain a “desirable place to shop, work, live, and play”, and a “quality, safe and clean environment for Capetonians, visitors and tourists”.

In 2017, the completed Zeitz MOCAA opened as a new outpost inside the less conventional venue; the old Grain Silo. The building in the Silo District, a former railway and shipping precinct that long served Cape Town’s busy shipping port is now Brutalism à la Heatherwick Studios.

Zeitz MOCAA and the Silo Hotel have called the Grain Silo home since 2017. Photo supplied.

Zeitz MOCAA and the Silo Hotel have called the Grain Silo home since 2017. Photo supplied.

The world-renowned studio collaborated with three local architecture firms: Van der Merwe Miszewski Architects, Rick Brown Associates, and Jacobs Parker Architects.

“[We] take the best of the structure and also some of the exuding gravity of the soulfulness of the original concrete. We’re exploring how you have texture and soulfulness in places,” Heatherwick told the V&A Waterfront during the planning stage.

“The former grain silo will be becoming a machine that’s working very hard. It will have 80 different gallery spaces with the most spectacular views of Cape Town.”

Heatherwick Studio’s goal to preserve structures while playing with the curiosity of contemporary art is apparent when entering the museum’s atrium, which was inspired by “carving the shape of a single grain, but enlarged through this building”, according to Heatherwick. The atrium and the surrounding space has elevators to connect the floors within tubes and spiral staircases through another tube.

This atrium bowl used to be sealed and was formerly part of the tunnels below the storage annex, which formed part of the basement level of the building, making it the lowest point of the building. Today, Zeitz MOCAA sits 57m above sea level at its highest point, the top of the former working house.

The atrium sits at the centre of the heart of the old storage annex. Photo supplied.

The atrium sits at the centre of the heart of the old storage annex. Photo supplied.

“The basement levels remained essentially the same since the original structure was built. They were used to extract the grain stored within the silos using iron wheels attached to them,” says Zeitz MOCAA. “You feel sheltered and protected when immersed and emerged within the building but exposed and vulnerable within the atrium.”

Adjacent to the atrium is the spiral staircase, which, together with the lifts in neighbouring silos, are like the spine of these spaces. These stairs are where form meets function. It fits perfectly within the confined space while fulfilling the necessary laws of steepness and form.

During the Zeitz MOCAA architectural tour, guests are told to go to the middle of the staircase and look up. “Designed to resemble a large drill bit and custom-designed to fit the dimensions of the silo bin. From one floor to the next floor, the stairs were carefully dropped into the tubes using a crane, then welded together and secured into the tube.”

“The building is defined by its ‘tubiness’ but there are also very crisp, clinical white box spaces that don’t impose the the characters of the historic building on you,” says Heatherwick.

The spiral staircase, inspired by an old drill-but exemplifies both form and function. Photo supplied.

The spiral staircase, inspired by an old drill-but exemplifies both form and function. Photo supplied.

Small but mighty Dust House

The initial purpose of the original dust house was to filter the air of the silo tubes and elevator areas to protect the lungs of the workers and to prevent the building from exploding. Although the Dust House remains relatively unchanged since its original form, today it is used as an experimental installation space for artists.

“The cutting, breaking, crushing, drilling, and grinding activities in the building release fine airborne silica dust, which can cause silicosis disease after inhaling over time,” says Zeitz MOCAA “Mechanisms sorted and released the dust and silicon dioxide that is found mostly in rocks like granite and sandstone, or soil, mortar and plaster.”

The Dust House also played a role in grain drying. The large cone-shaped turbines seen from outside sucked in fine dust-particles. Friction between the particles could spark and cause fire.

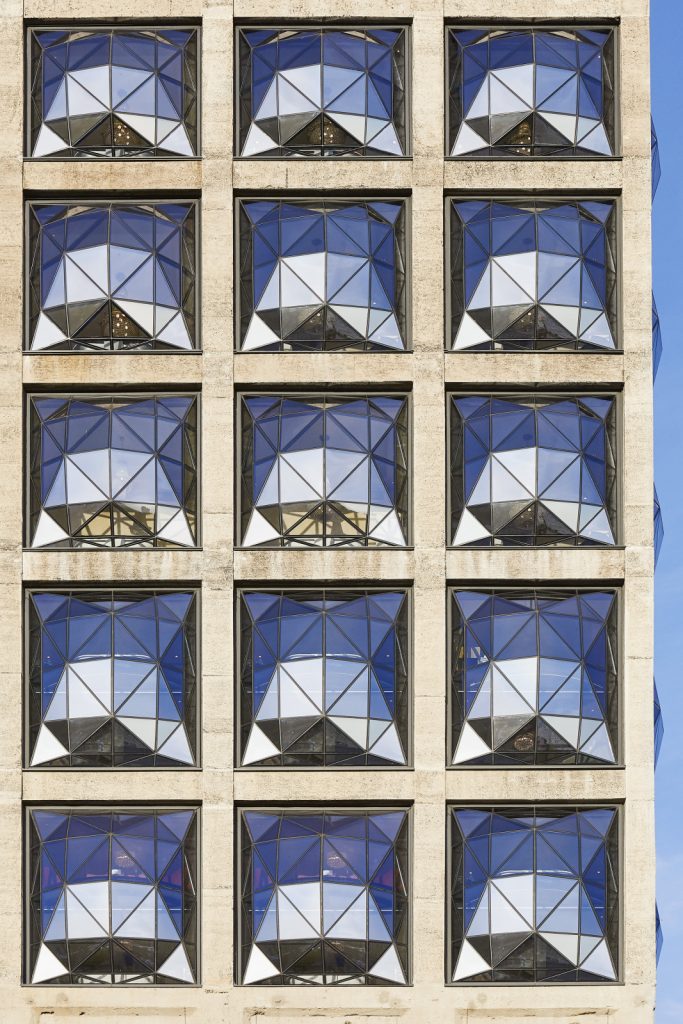

Cushion windows

Take the trip the level six up the spiral staircase or the elevators to experience the triangular cushion windows. Each window reflects the sky. The reflection of a single window grabs the different views of Cape Town and brings them together.

“Made from double glazed performance glass cut into triangles and then mounted into the framework of steel bars gives the feeling of a mirror bowl. The windows provide multiple views of the harbour and different angles,” says Zeitz MOCAA.

The triangular shape is inspired by pressure points of the building that the designers at Heatherwick Studios observed on a digital 3D model of the building.

The cushion windows are designed to make the building “breath”. Photo supplied.

The cushion windows are designed to make the building “breath”. Photo supplied.

Heatherwick’s vision for the windows was to make it seem like the building is breathing and releasing the pressure from inside. The design makes solid glass appear malleable and flexible, which contrasts with the rigid concrete and metaphorical pressure of all the grain once held inside each tube.

As a beacon for art in Africa, Heatherwick wanted the building to be seen as a lighthouse looking out to sea. The windows also play with reflections experienced outside the building, making this top level of the building visible.

“What was so influential to the design is that we developed its original function as part of this collective grain system in the whole of South Africa,” says Heatherwick. “It’s unique because it’s made from big concrete tubes, but there is no space, no floors. So we had to figure out how to put floors and make spaces in a building made from tubes.”

On the rooftop terrace, glass panels on the floor look daunting to walk across but are secure for visitors to walk on. A unique experience is to look down through the glass panels, which gives a birds-eye view of the atrium bowl and provides some natural light into the space.

Enter the trackshed and gantry

The entrance to Zeitz MOCAA is through the former trackshed, an original structure of the silo. The grain was brought in along four railway tracks, which you can still see along the ground outside the museum.

When leaving the building, guests may notice machinery on the left side of the entrance doors. It would pull the railway carts at an angle to pour out the grain circulated through the building.

“A lot of the old industrial steel works and machinery of the old grain silo was stripped out before reconstruction and preserved at a yard in Philippi, Cape Town, where it was sand-blasted, painted, and then reinstalled later,” says Zeitz MOCAA.

Despite housing contemporary art and creative experimentation, the former Grain Silo should not be seen in isolation, but rather as part of a grain system that covered the entire country. Alone, it would have had no use, and would never have been built.