Chester and Papa Action in a car in the series ‘Yizo Yizo’. (The Bomb Shelter)

In his 1889 essay The Decay of Lying, Oscar Wilde opined that “life imitates art far more than art imitates life.”

However, in exceptional instances, life unfolds and, when immortalised through capture, assumes a form where those previously unaware of the unfolding perceive life as intricately shaped by the art that mirrors it — an essence embodied by the work of Teboho Mahlatsi, who died on 3 July at the age of 49.

Lauded as a luminary among trailblazing black South African filmmakers, Mahlatsi’s origins can be traced back to Kroonstad, a modest enclave in the north of the Free State.

In an epic tale of a post-apartheid South Africa in search of its identity, Mahlatsi emerged as a protagonist in an ensemble of visionaries. He was cast in the role of a young man with an innate gift for storytelling, imbued with the power to put black lives into vivid motion pictures, gracefully panning through a shifting landscape and making art of an actual lived experience.

In a 2010 Ted Talk, Mahlatsi answered a question about his reason for making movies, and what kind of filmmaker he was, by saying, “I make movies because I am first and foremost a fan of cinema … Like a typical township kid, I fell in love with cinema from going to the bioscope. I don’t consider myself an African filmmaker — there’s a particular connotation that comes with that — I’m just a filmmaker.

“I create essentially popular films. I’m like the Brenda Fassie of films. I want to entertain. I want to make films for that township kid who went to bioscope like I did.”

Borrowing Professor Njabulo Ndebele’s description “politics of the personal”, the stance Mahlatsi took was that of the “cinema of the personal” — films that spoke, first and foremost, to his environment and to himself. This is evident in his work, from the seminal series Yizo Yizo to Portrait of a Young Man Drowning, Sekalli le Meokgo and even his adverts.

Faced with the task of capturing a life well lived, I discerned the truest portrayal of this towering figure was to be found in the voices of those who have thrived because of the foundation he laid.

This article does not look to frame or contextualise the memory of Teboho Mahlatsi, instead, its purpose is to find his voice still resonating in the voices he touched.

Although filmmaking was his predominant medium, at his core Mahlatsi was a storyteller. An astute one of the highest African order. And it is his bravery in honest storytelling that inspired filmmakers, advertising executives and playwrights alike.

As an ode to his contributions, I gathered the musings of three black storytellers who in their own modes and mediums have embraced honesty in the tapestry of how they communicate the vastness of the black lived experience.

When films are being made, often the sacred blueprint of a storyboard stands as a formidable bulwark safeguarding the artistic vision. To know our characters, our world, our given circumstances, and how all these combine, we look to the storyboard to be our anchor.

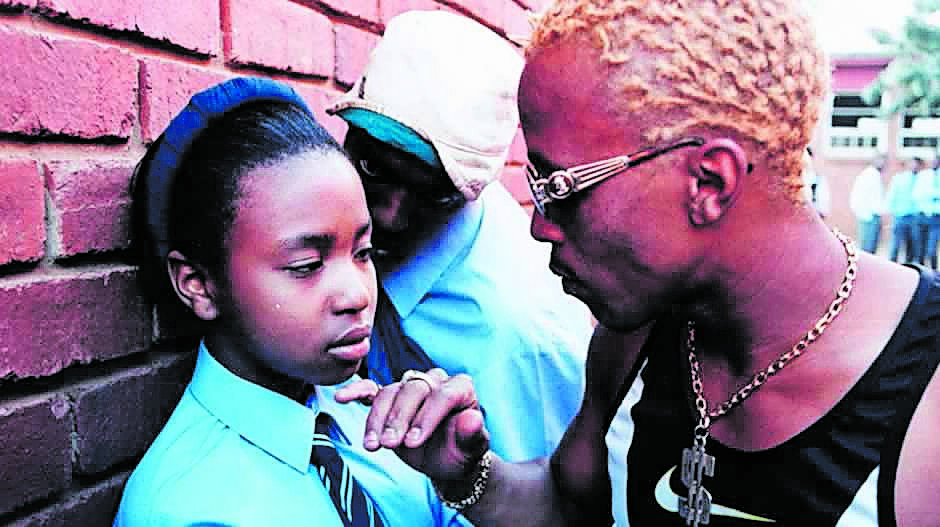

Chester harasses Hazel at school in the series ‘Yizo Yizo’. (The Bomb Shelter)

Chester harasses Hazel at school in the series ‘Yizo Yizo’. (The Bomb Shelter)

Allow me to introduce for Act 1:

Mmabatho Montsho, a filmmaker:

“Like most South Africans of my generation, my first encounter with Teboho’s work was Yizo Yizo. At the time, my impressions were not necessarily about the filmmaker but of the art itself. The most visually distinct thing was the colouring of the series — I had not seen something like that on TV.

“The hyper-real acting style, use of language, and exploration of themes was utterly compelling. It did for me what I think a great TV show should do — I forgot about the artists and got lost in the art.

“Yizo Yizo marked a turning point in treatment. It impacted the style of acting; the use of both spoken and cinematic language that felt colloquial. It also opened doors for a certain type of actor and performance that may have not found space in the mainstream.

“It sparked what some regard as the ‘kwaito era’ of South African film- and TV-making. Yizo Yizo did for actors what YFM did for the radio broadcaster. The style remains a blueprint for hyper-real drama today.

“In my short film Joko Ya Hao, the opening scene is a woman washing her bloody hands in a bowl of water. I wrote and directed that scene as homage to a visceral moment in Portrait of a Young Man Drowning, where the young man washes his hands in the bowl that is traditionally placed outside the gate of a home for mourners to cleanse their hands when returning from the graveside.

“The symbolism and poetry of that moment stuck with me for years, and when the opportunity arose, I paid my homage.

“If I were to keep it strictly local, I’d say the depth of research and how it translates to the screen remains unmatched. Look at Portrait of a Young Man Dying and Sekalli le Meokgo and how he brought familiar worlds of story to the screen in a philosophical approach.

“He was truly pioneering a South African brand of ‘cinema of the personal’ which did not feel self-referential.”

Slow fade to black. Queue music.

The song is a Zola kwaito jam, as the cut jumps we hear, “And if I die, badde lam’ uhlale wazi ngiyak’thanda” (my buddy, always know that I love you.)

The jump cut does not take us out of the township because “thina ekasi siGhetto fabulous”. The rhythm of the shots scored to the rhythm of township anthems lets us know even in his last dance, iBadde lethu lohlala listhanda (our buddy will always love us).

More than the epic loss, we celebrate the gains of the gift he left.

A close-up of Bobo the drug addict. (The Bomb Shelter)

A close-up of Bobo the drug addict. (The Bomb Shelter)

Cut 1. Act 2:

Location: The township

Year: The mid-1990s

Music: Kwaito

South Africa, the beacon of African advancement, continues to exist in the developing world paradigm. The artists who practise their trade in forms that have been widely practised in the West find themselves having the duty of Africanising the tropes and technologies with which they apply their craft.

What Plato made of theatre in Ancient Greece, Jefferson Tshabalala has to fashion for the modern-day lokishi palate. It is easier for him to do this when his predecessor took the cinema of Orson Welles and located it in Yizo Yizo’s Supatsela High School. The tools may be of the West but the tales are of the South.

Trailblazer: Teboho Mahlatsi was a film director and producer at Bomb Shelter Productions. Photo: Robert Tshabalala/Gallo Images

Trailblazer: Teboho Mahlatsi was a film director and producer at Bomb Shelter Productions. Photo: Robert Tshabalala/Gallo Images

Enter Jefferson Tshabalala,

a theatre-maker:

“It was through the iconic Yizo Yizo. I remember thinking, even as a kid, that that’s what I want to do. To tell stories about black people. I had never known anything like it. I knew I wanted to be in the arts but that programme made me know what that could look like.

“When I think of [Yizo Yizo characters] Bobo, Hazel, Javas, Mantwa, Chester, Papa Action, Thiza, Nomsa — I imagine people who are true, authentic, well-rounded and clear in their township lived experience.

“That is a trace in my work that I feel Tebogo paved for many of us — to not apologise about the splendour and vast scope of what black characters can be and become.

“This work is rightfully in the canon. It shifted and informed a defining cultural moment in how artists and art speaks about a country in ruin as it relates to its majority and especially its youth.

“A genius of his time, Teboho knew what we needed before we did, and to go onto un-ventured terrain bravely makes him a pioneer a cut above many.”

In the montage, we see the stage. We see the screen. We see the curtain. We see the lens. We see the lights. We see the grading. But, above all, whether live or on screen, we see black people in their fullest glory.

Cut 2. Act 3.

Stories and their telling are not limited to the domestic dramas and political satire for which South Africa is well known. There are also stories of corporations, brands, institutions — and they use storytelling to engage the consumer, investors and their internal staff at large.

Mahlatsi was a maverick in how he used his gift for telling stories to connect brands and people. From a long art form to a discipline that requires tales to be told in seconds, Mahlatsi was a master in all mediums.

Hailed as one of the youngest black directors to pioneer in film, his reach extended to would-be young black executives in the advertising space.

Enter Kagiso Tshepe, an advertising creative

“In retrospect, I realise that before the magnum opus that is Yizo Yizo, I had encountered The Brother’s work in what was my childhood favourite TV moment — commercials.

“His work for some of South Africa’s most iconic brands had something that drew me in — something familiar. It was a world inside the TV that looked and felt like the world around me, but seen from a beautiful eye.

“Teboho’s approach to storytelling in Ad Land was as brilliant as it is in long form. He showed me my reality in a way that made me fall in love with every scene I saw in my family, on my street, at church and even in my school.

“Through his lens, township life and the black experience became a celebration, remarkable and worthy.

“Yizo Yizo is a university. It’s a whole degree. It’s a school that I believe every creative in this country, especially if you’re black, must go to. It must be studied. There is so much to learn from that work.

“Even before we get into the nuances and the jewels of it, the amazing thing is that Teboho and the team at Bomb made such a piece. Just the fact that they gave us Yizo Yizo is more than enough to write an entire thesis of gratitude to Teboho Mahlatsi. The Brother, thank you.

“The Brother was a pioneer; it was not only our eyes he opened but also the doors into an industry that seemed unattainable to most of us. He was, and will forever be, a great reference.

“You can’t talk about advertising films in South Africa without referencing his work. Not a single creative, regardless of race, will argue with that. His ability to balance a fantastic story with authenticity and respect is unmatched. It’s something I admire about him and has become a big influence that I always try to bring into my own work.

“I’m very grateful and privileged to have had the opportunity to work with Teboho on a few projects — and what a pleasure that was.

“He collaborated in a way that obliterated titles and collapsed hierarchy, where differences in age, work experience, quality of language, or any of the silly things that generally get in the way of most collaborations, he dissolved it all and created a calm and inspiring space for everybody, because only the work mattered and everyone was allowed to bring themselves into the work.

“That’s what made most of his work so human. Yes. Humility and humanity — that’s it.

“That’s what I’ve learned from The Brother and I hope to practise and share it with everyone.”

Tail slate.

Teboho Mahlatsi skilfully wielded the craft of cinematography to present an intricate triptych of South Africa’s essence, employing a trinity of lenses that unveiled the nation’s complexities. He harnessed the midshot to depict the familiar, revealing aspects of the black collective consciousness.

Then, with the precision of a super extreme close-up, he peeled back layers, prompting a visceral confrontation with our perceived understanding. Yet it was in the artful zooming out, that he transcended boundaries, capturing the grandeur of the broader world.

With these lens shifts, Mahlatsi engaged in a dynamic discourse with blackness, employing the wide shot to encompass the tapestry of black identity, the midshot to illuminate the narratives of black people, and the close-up shot to intimately explore the essence of individual black lives, each frame a symphony of revelation and introspection.