Nigerian

author Chinua

Achebe

and Nelson

Mandela

chat on

12 September

2002 prior

to Achebe

receiving an

honorary

degree from

the University

of Cape Town. (ANNA ZIEMINSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

Unthinkable now, in 2023, that there was a time when English literature courses the world over were taught with no mention of African literature. Or, as puzzling, with nods only to a particular form of writing about Africa, as Chinua Achebe noted when reflecting on his schooling:

“I read lots of English books there [at Government College, Umuahia]. I read Treasure Island and Gulliver’s Travels and Prisoner of Zenda, and Oliver Twist and Tom Brown’s School Days and such books in their dozens. But I also encountered Ryder [sic] Haggard and John Buchan and the rest, and their ‘African Books’.”

Haggard and Buchan wrote in the enveloping glow of the British Empire at its height, about adventurers who overcame odds that would have overwhelmed mere mortals, triumphing in pitched battles against foes they regarded as savage natives.

These were the “African” tales that Achebe’s secondary schooling at an institution in Nigeria modelled on English public schools exposed his sensibility to, but just as well, for reacting against this morass of cliché and prejudice — “witch doctors”, noble black retainers laying down their lives for their British masters, etc — was to prove instrumental in his writing life.

It was not only in rebuttal of superficial, ignorant and racist portraits of Africans that Achebe was to write. His was also a progressive and empowering programme — to give to readers a rounded and accurate sense of people, place and time.

Africans were no longer to be the backdrop to the derring-do of white protagonists, nameless cyphers in a cast of hundreds or thousands, and faceless and ultimately disposable presences on the page.

But offensive though the novels of Haggard and Buchan were to Achebe the youth, it was the literary giant Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness that he came most to revile. His feelings and contentions about it were most clearly and robustly articulated in middle age, when he gave a lecture at the University of Massachusetts Amherst in the US in February 1975 titled “An Image of Africa: Racism in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness”.

It set off debate that rages until today, with Conrad now removed from the syllabi of many university literature departments and widely denounced on the basis of Achebe’s lecture. (Some of the detractors, it is clear, have not engaged with Conrad’s actual work.)

The countervailing view has been put forward cogently by, among others, the historian Adam Hochschild, whose best-known work is the withering exposé and critique of genocidal Belgian colonialism in the Congo, King Leopold’s Ghost.

Achebe in Abuja, Nigeria, in January 2009. (Photo by ABAYOMI ADESHIDA / AFP)

Achebe in Abuja, Nigeria, in January 2009. (Photo by ABAYOMI ADESHIDA / AFP)

But this particular point of Conradian contention is for another day. That Conrad’s novella was a major presence in defining, classifying and categorising what constituted “African literature” is brought home by the experience of Nobel Literature laureate Toni Morrison.

Presenting Achebe with the African American Institute Award on 22 September 2000, she said, “In 1965, I began reading African literature, devouring it actually … the jolt these writers gave me was explosive.

“The confirmation that African literature was not confined to Doris Lessing and Joseph Conrad was so stunning it led me to secure the aid of two academics who could anthologise the literature.

“At that time, African literature was not a subject to be taught in American schools … discovering how to eliminate, to manipulate the Eurocentric eye … I attribute these learned lessons to Chinua Achebe. In the pages of Things Fall Apart lay not the argument but the example …”

And so we come to Things Fall Apart. Fearing that its style and subject matter — both revolutionary —might prove off-putting to readers, it had a less-than-modest first print-run of 2 000 copies in 1958. By the turn of the millennium, it had sold more than 10 million copies in 45 languages.

This piece is both a review and a re-view of Things Fall Apart. It cannot be otherwise — thousands of reviews, critiques, dissertations, theses, scholarly articles, journals and books have pored over Achebe’s first novel since it was published in 1958.

Things Fall Apart has been a recurring experience in my reading life, first, at university in 1978; a re-reading prompted by Nelson Mandela’s tribute in honour of Achebe’s 70th birthday on 16 November 2000: “There was a writer named Chinua Achebe in whose company the prison walls fell down”; another visit on its 50th anniversary in 2008; a selective encounter in the weeks after Achebe’s death on 21 March 2013 and before writing this.

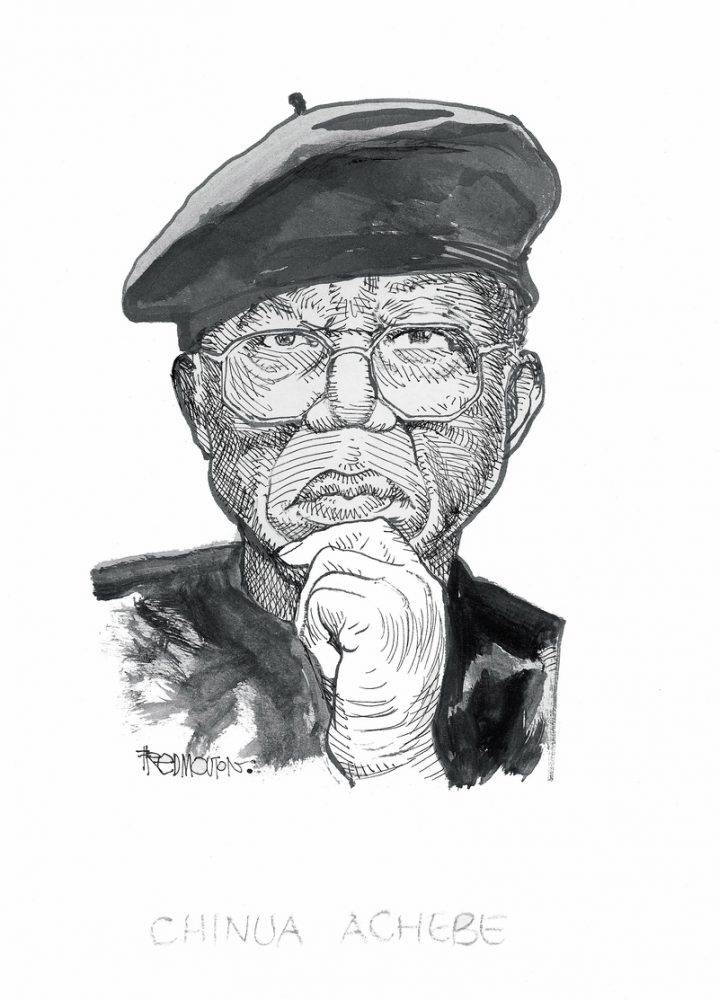

Illustrious: Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, best known for his novel

‘Things Fall Apart’.

Illustrious: Nigerian author Chinua Achebe, best known for his novel

‘Things Fall Apart’.

Despite its iconic status, a sketch of aspects of the plot is useful, on the assumption also that at 65 the book is old enough to be new to some.

Achebe begins directly and alluringly, his first sentence telling the reader that “Okonkwo was well known throughout the nine villages and even beyond”. He is famed and revered in his home village of Umuofia for his wrestling exploit as a youth of 18, when he defeated Amalinze the Cat (“Cat because his back would never touch the earth”), the great wrestler who held sway unbeaten for seven years in the wider region.

It is 20 years since this early achievement, during which Okonkwo has become a prosperous farmer with two barns of yams and three wives. He has built this from nothing because his shiftless father Unoka is a loafer and a borrower, allowing his wife and children to go hungry and racking up debt. But he has a roguish charm, an ability to persuade neighbours to send good money after bad.

As a farmer, Unoka is irresponsible and lazy. As Chika, the priestess to Agbala, the Oracle of the Hills and the Caves, berates him: “You, Unoka, are known in the clan for the weakness of your matchet and your hoe. When your neighbours go out with their axes to cut down virgin forests, you sow your yams on exhausted farms that take no labour to clear.”

The contrast with Okonkwo could not be more extreme. Inheriting no barn and no title, Okonwo nonetheless has taken two titles and “shown incredible prowess in two inter-tribal wars”.

“And so although Okonkwo was still young, he was one of the greatest men of his time.”

That he is, but Okonkwo is not free of blemishes. He is heavy-handed with his wives and children, all of whom fear his fierce temper. Tellingly: “Perhaps down in his heart Okonkwo was not a cruel man. But his whole life was dominated by fear, the fear of failure and of weakness.”

Most of all, Achebe tells the reader, it is the fear of being thought of as resembling his father. And this despite building up his barns and reserves of yam through early and conscientious share-cropping for wealthier neighbours; despite the reverence his martial achievements have earned him and despite not having the sort of bad chi (personal god) that blighted his father’s life.

When a woman from Umuofia is killed in nearby Mbaino, war is avoided by the latter offering as compensation a young man and a virgin. Into Okonkwo’s care is placed Ikemefuna, and his fate sets in motion the tragedy of Okonkwo.

This sketch of the first of the novel’s three parts gives a sense of who and what Okonkwo is. He is often simplistically represented in readings of the book as a marker of tradition resisting modernity but that is only a small measure of all for which he stands. In parts two and three Achebe recounts the coming of the Christian missionaries and the brutish interventions of the district commissioner.

For the first seven years of this, Okonkwo is banished. (No clues or spoilers here — read the novel to find out why!) On his return, he must face the conflicts that have developed between the people of Umuofia and the colonial incomers and their religion, culture and administration.

It is this vividly and unsentimentally evoked clash that, for some, places Things Fall Apart at the forefront of postcolonial literature.

Decades before such acclamation, Achebe was celebrated as the father of the African novel, an honorific refined and expanded by the philosopher and novelist Kwame Anthony Appiah to “the founding father of modern African literature”.

Achebe is both those, and something more — a great thinker bringing to bear powers of observation and recall to present a detailed and forensic picture of Igbo life, culture and civilisation before all those and many other things fell apart.