Over five million people worldwide had started using PrEP by September 2023. (Tony Webster)

By September, over five million people worldwide had started using PrEP (short for pre-exposure prophylaxis). This means taking medicine before sex to prevent getting infected with HIV.

At just over a million users, South Africa makes up about a fifth of the total.

These sound like big numbers — and they indeed point to progress in the fight against HIV, considering that the World Health Organisation (WHO) added these drugs to the medicine cabinet only eight years ago — but the uptake still falls well short of the UNAids global target of 10-million PrEP users by 2025.

And Monday’s release of the results of the Human Sciences Research Council’s latest HIV household survey makes achieving this goal even more urgent: condom use in South Africa is declining. Less than half of the almost 72 000 people interviewed used a condom the last time they had sex — which means getting people to use HIV prevention medication is crucially needed.

Despite people being slower to start taking these prevention pills than public health authorities had hoped, two new, longer-acting choices — a monthly vaginal ring and a two-monthly injection — have come onto the scene in the past two years.

These advances can help the world rethink HIV prevention. But can they translate into choices that actually work for people, and so help slow down new HIV infections?

We believe the answer to both questions is yes — if we put in practice the lessons learnt from rolling out oral PrEP to make it easy for people to get these new products when, where, from whom and how they need them.

Here are four lessons to guide HIV prevention programmes going forward.

- Rethink risk

Many early oral PrEP programmes targeted groups that were thought to have a “high risk”, such as sex workers and men who have sex with men. These groups are called “key populations” as they have a bigger chance of contracting HIV and, because of social and legal stigma, often struggle to access treatment or prevention services.

While data from UNAids show that around 70% of new HIV infections occur among key populations and their partners, someone’s chance for contracting HIV can change depending on with whom and how they are having sex, for example whether a partner knows their HIV status and whether they use protection or not. To get the most out of PrEP, programmes and policies need to reframe the idea of risk so that it fits better with the lifestyle and experiences of those the medicines aim to help, instead of narrowly focusing on population groups.

Research shows that HIV prevention is not a priority for many people who have been thought of as in the high-risk group in the past, nor do they think about their chance of getting HIV in the way healthcare providers do. Instead, managing a relationship and looking after their sexual health are more important. Talking to potential PrEP users only about how the drugs can stop them from getting HIV may therefore not entice people to learn more about PrEP, start using it or use the medication in the most effective way.

For example, a programme in South Africa helps young women think about PrEP as part of a “journey” of self-empowerment, during which they consider what they want their future to look like and identify the support — including to protect their sexual health — they’ll need to realise those goals.

If HIV prevention is thought of in terms of sexual health and maintaining healthy relationships, health workers can help their clients understand how using the medicines can contribute to these goals — even when the chance of getting HIV isn’t their main worry. Experts say pitching PrEP as a way to reduce anxiety, take control over their sexual health, increase sexual satisfaction, pleasure and intimacy, and stay safe and healthy can help people see a better future.

- Drive up demand

Thinking that people will use new products and interventions simply because they were developed doesn’t hold. If the demand for these products doesn’t exist, they won’t get used.

When oral PrEP was first introduced, ideas about what people wanted or why they’d want the pills weren’t considered much, and so initial uptake was low. Programmes eventually realised that to get more people on board, there’d need to be broad, sustained and user-centred efforts to create demand for the products.

Because people from key populations are often shunned by society, they may struggle to get preventive medicines or treatment for HIV. Drives tailored specifically to the needs of these groups can help to curb the spread of HIV.

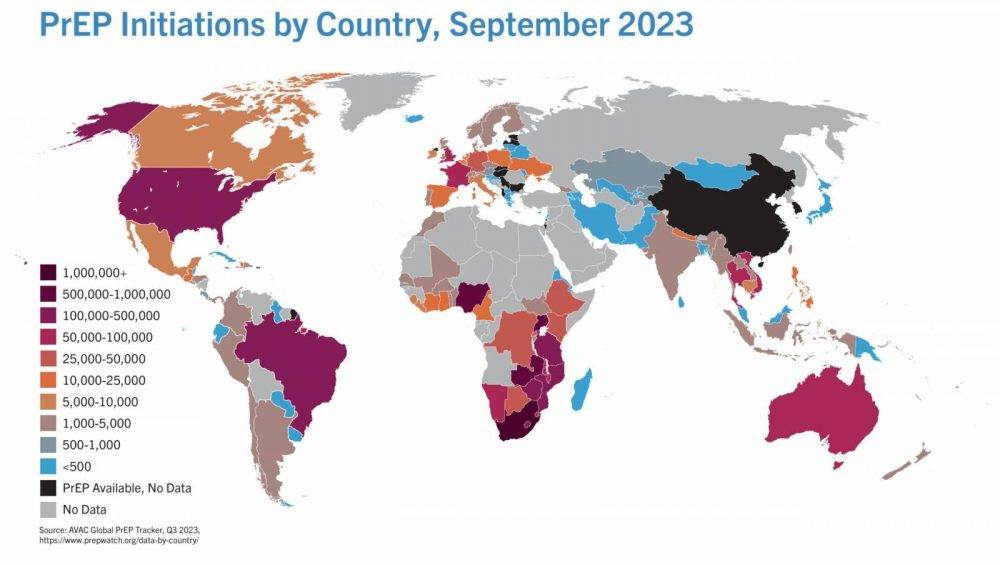

Avac follows global PrEP use through quarterly user surveys and data from drug manufacturers and government agencies. This graphic shows what PrEP use looks like around the globe. See more at PrEPWatch. (PrEPWatch/Avac)

Avac follows global PrEP use through quarterly user surveys and data from drug manufacturers and government agencies. This graphic shows what PrEP use looks like around the globe. See more at PrEPWatch. (PrEPWatch/Avac)

In Kenya, for example, the Jilinde project looked at how people’s behaviour drives their choices about using a product and divided the target market into specific subgroups to shape messages and strategies to the needs of teen girls and young women, female sex workers and men who have sex with men. (Jilinde is a Kiswahili word that means “protect yourself”.)

The project used both mass media — for widespread awareness — and interpersonal communications — for focused outreach. Social media, community engagement and drawing on existing networks were central to their approach. Importantly, apart from only handing out the pills, the project also helped people to understand that they had to take the medicine every day to get the best results.

To get people on board, messages pitched PrEP as a general health intervention rather than targeting specific groups, and so created a more inclusive environment for PrEP uptake, free of stigma. The programme also helped journalists and media outlets to put out accurate information about PrEP, so as to prevent stigmatisation and encourage wider acceptance.

Using this approach, the Jilinde project signed up almost double the number of people for PrEP than they initially thought they would over five years: 37 806 instead of the planned 20 776.

- Think about places, providers and peers

Where people get their prevention medication and how they’re supported drive the success of PrEP programmes.

For example, with the Jilinde project, people could get their pills from drop-in centres, public clinics or private health facilities linked to clinic services in community centres. Drop-in centres — places where people can get health services from without it feeling like going to a clinic — were most popular: almost two-thirds (64.5%) of the people who got PrEP through the project preferred this route, which shows that walk-in centres could be a good way to reach female sex workers and men who have sex with men (who made up 64% of Jilinde’s clients). Teen girls, young women and couples instead chose clinics — either public or private.

In South Africa, the Desmond Tutu Health Foundation’s FastPrEP programme uses similar thinking to get more people to use PrEP, with a mobile clinic serving as a central base that connects to other clinics, pharmacies and youth centres, which then distribute the medicines. The results from these programmes show that different platforms work for different people.

Allowing nurses, pharmacists and community health workers to help with prescribing PrEP or telling people about it, can also take prevention further than HIV clinics. For example, in Kenya, Namibia, Uganda and Zimbabwe, health practitioners only have to complete a three-day course in order to give people advice on taking HIV prevention medicine. In August, the South African Pharmacy Council got a judicial go-ahead to start its programme to train pharmacists to manage and prescribe anti-HIV pills.

Peers can also play an invaluable role in supporting effective PrEP use. A peer-to-peer method to increase PrEP use among female sex workers in Zambia almost doubled the number of new uptakes, compared with only about a quarter more signing up when it’s left only to clinics and health workers to spread the word.

Similarly, in Zimbabwe, young women were trained on PrEP and HIV prevention and then went into the community where they talked to others and taught them about the medication. The trainers also helped to link their peers with centres where they could get the pills from. The training package included lessons on gender-based violence, sexual health and self-care, which helped the women deal with issues that could make it hard for them to consider PrEP. As a result, the uptake of HIV prevention pills increased by 59% in the district in the seven months after the training.

- Champion choice

For the first time in the history of the HIV epidemic, prevention programmes can now be built around choice, with straightforward language about risks and benefits of different prevention methods, as well as supportive counselling to help people decide which option is best for them.

This model has worked for years in the contraceptive field.

Having real choices in healthcare is effective, as they empower people and support them in switching methods if and when they need to.

This could drastically change HIV prevention, but only if the people who will use the products lead the way.

In September in Uganda, a group of young women from east and southern Africa formed the African Women’s HIV Prevention Community Accountability Board and launched the Choice Manifesto. The statement calls on governments and donors to make funds and systems available so that more people can have access to the full range of HIV prevention options.

This week, the Global Key Population HIV Prevention Road Map will be launched at the International Conference on Aids and Sexually Transmitted Infections in Africa in Harare. It was put together by a group of people representing key populations — including sex workers, men who have sex with men, trans and gender-diverse individuals and people who inject drugs — and outlines a plan for getting HIV prevention services to these groups in a fair way across the world.

The messages of these two new campaigns are clear: “This is what prevention needs to look like for us and it needs to be led by us.” And although scientists, policymakers and funders must keep on driving programmes, it’s community leadership and mobilisation that will end the HIV epidemic — but only if these voices are heard.

The world cannot afford to squander another decade through slow, fragmented roll-out of life-saving HIV prevention. With longer-lasting options now becoming available, along with daily oral PrEP, condoms, voluntary medical male circumcision and HIV treatment, the world could finally bend the curve of HIV — but only if investment and planning for delivery are as evidence-based, person-centred and innovative as research and development in new products.

Wawira Nyagah is the director of product introduction and access at Avac, and Mitchell Warren is Avac’s executive director. More at www.avac.org and www.prepwatch.org.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.