ALL HANDS ON DECK: Women's health specialists and academics led an outreach at Grassland Secondary School, Mangaung, meeting 200 teens and 50 parents on teen pregnancy solutions, while also training health workers on the issue. (Zozo Nene)

December holidays started badly for Ainsley Robinson*. At 14, she wanted to hang out with friends; instead she was stuck helping her mother in their tiny kitchen in their cramped zinc shack in Hopetown in the Northern Cape, about 120km from Kimberley.

What’s more, there was tension between Ainsley and her mother over her new boyfriend, an 18-year-old who was already out of school.

As they chopped vegetables for dinner, Ainsley’s mother watched her closely. Her daughter’s body had changed, she noticed. Her breasts looked swollen.

Determined to find out what was going on, she took her daughter to the clinic the next day, where nurses confirmed that Ainsley was three months pregnant.

Her mother was upset — she knew too many teen mothers in Hopetown already.

Ainsley was 15 by the time she gave birth, in July last year. The clinic referred her to the Hopetown Community Health Centre for the birth.

“They had to cut me at the hospital to deliver the baby — he was too big,” recounts Ainsley, referring to an episiotomy, a procedure in which doctors cut the area between the vagina and the anus to create a bigger space through which the baby can come out.

Many young mothers in SA have HIV

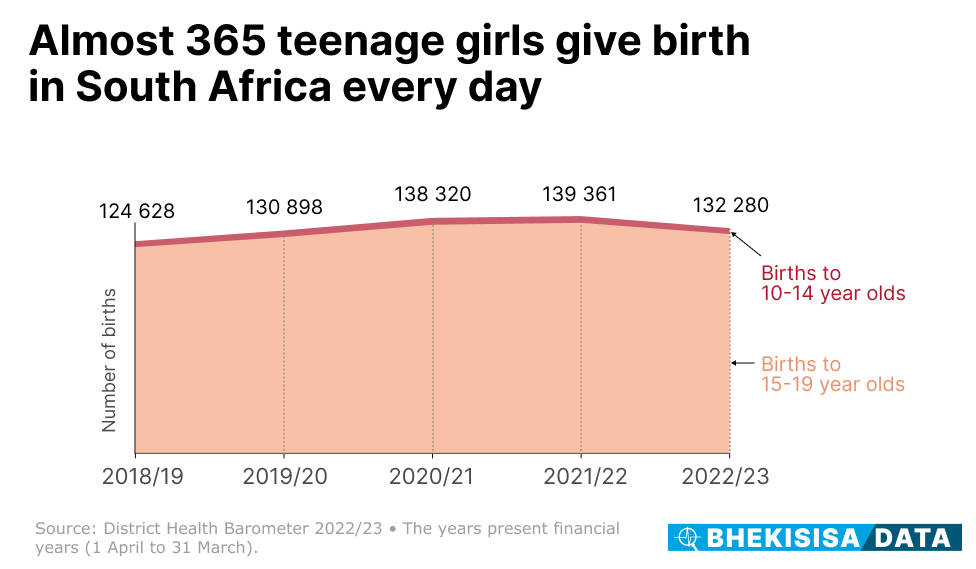

Ainsley is a young girl like one of close to 365 teens who give birth in South Africa every day, figures from the 2022/23 District Health Barometer show. The yearly report gives an overview of public sector health services in the country, including for pregnancy and childbirth.

Of that daily number of births, 10 are to girls who are not even 15 years old yet.

The World Health Organisation looks at a country’s teen pregnancy rate (that is, the number of girls between 10 and 19 who give birth out of the total number of girls in this age group) as one check to see how well a government is doing at improving healthcare for its citizens.

Although teen birth rates around the world have come down since 2000, there were still about 1.5 births per 1 000 girls between 10 and 14 years old in 2023.

That’s also where the rate sat in South Africa in 2020 for this age group, a 2022 study in the South African Medical Journal showed. But it was almost 50% higher than the 1.1 per 1 000 girls in 2017, with the authors estimating that it would have risen to 1.6 the next year.

It’s lower than the rate of 4.4 per 1 000 girls seen in the rest of Africa, though.

But, says Peter Barron, public health consultant, and his co-authors in that study, the figures are “very high” compared with what’s seen in developed countries.

High numbers of teenage pregnancies are bad news for a country’s development outlook, because having a baby as a teenager often means a girl has to drop out of school. It starts a vicious cycle: not being able to finish school shrinks her chance of further studies or getting a job, which means she has to rely on a government grant to care for her child and she and her children continue to live in poverty.

Moreover, many young mothers in South Africa also have HIV, (close to one in five in women aged 15 and 24 who recently had a baby, data from the Human Sciences Research Council shows).

“Any girl that’s pregnant in that age group [10-14 years old] represents a train smash, because it’s likely to be [due to] non-consensual sex — statutory rape, ” says Barron.

Poorer provinces have more teen pregnancies

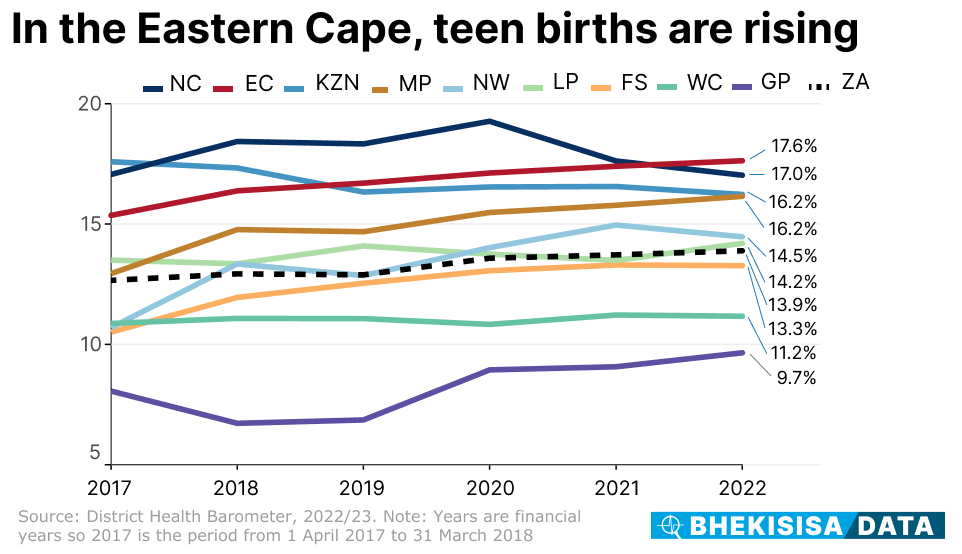

While South Africa’s number of teen births in 2022 was about 5% lower than the previous year, the figure has been steadily climbing by about 1.5% every year for four years before that.

That’s not what you want to see over time, according to Barron.

“Look at what’s happening in the United States,” he says, “where year-on-year, the teenage pregnancy rate has been decreasing solidly for 30 years. Ideally, that’s what you’d like to see in a developing society, because as people’s educational and economic prospects improve, the chances of them falling pregnant at a young age decrease.”

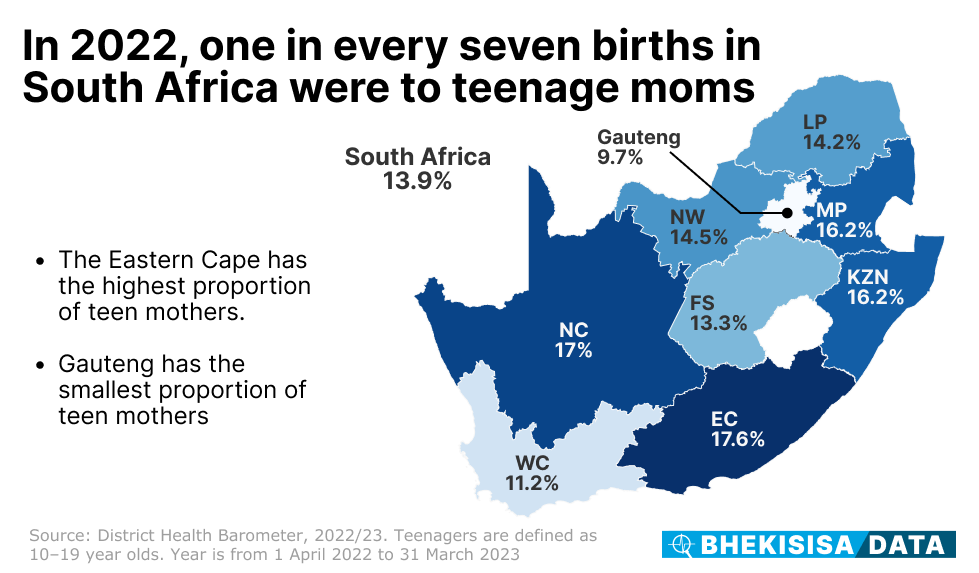

Even though the trend seems that numbers have started coming down in the Northern Cape over the past two years, the province still has the second highest number of teen mothers in the country. The Eastern Cape tops the list — and the numbers there are climbing steadily. Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal share third spot, with close to one in every six mothers in these provinces being younger than 20.

These are also the provinces where half to two-thirds of adults are living in poverty, people struggle to get sexual health services and a large part of the population are teenagers.

Gauteng and the Western Cape — the only two provinces where the proportion of teen mothers are well below the national figure — are also the ones with the lowest rates of poverty (around 30%).

Zozo Nene, president of South Africa’s College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, says in the Eastern Cape and Northern Cape teens also battle for services such as contraceptives and abortions, and proper sex education is lacking.

“They aren’t mature enough to grasp the consequences of having sex. Parents and teachers often don’t discuss sex and sexuality with them because they are seen as ‘children’. Initially, they might hide the pregnancy, not recognising what a missed period means, and later out of shame. This leaves them to deal with the pregnancy alone,” she says. “They often start prenatal care late, if at all.”

What’s the fix?

Teaching kids better life skills, such as helping them understand abusive relationships and why safe sex is important, and improving sex ed at school can help, the authors of the District Health Barometer say, together with making sure that young people can get things like condoms and contraceptives without stigma.

It’s something the health department’s plan for having these available through vending machines could help with.

Eight such machines have been set up in the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal since April as part of a health department pilot project, and five more are to follow before the end of March next year, the department told Bhekisisa.

Despite there still being regulatory hurdles to pass before the daily birth control pill can be dispensed through the machines, a self-help system like this could be part of the solution to fix the unmet need for family planning in South Africa, a presentation showed at the International Aids Society conference in Munich in July.

In cases where teen births decreased, it’s been because everyone — from government, academics and health workers to NGOs, religious groups and the private sector — makes it their responsibility to get things to change, says Nene.

The professional body which oversees the specialist training of obstetricians and gynaecologists in South Africa, who Nene calls the “custodians of women’s health”, is embarking on visits to all nine provinces in the coming months and early into next year to train healthcare workers on helping teens get contraception and respectful care.

“As healthcare providers, we see these teenagers when they are already pregnant. I would like us to change this, to intervene before they are pregnant.”

For that, she says, teenagers have to be able to make informed choices about their reproductive needs, which is why she feels strongly about teaching health workers how to work with young people and give them reliable, evidence-based information.

“As long as healthcare workers keep making decisions for them, instead of letting kids take responsibility for their own lives, it’s unlikely we’ll get buy-in from them.”

Why staying in school is important

For Ainsley, things turned out well. She went back to school after her baby was born and is completing grade 8 this year.

She’s lucky to have found the support of one of her teachers, Pamela Jaquire.

Jaquire understands exactly how much a surprise pregnancy can disrupt a young life.

“I was 17 when I got pregnant,” she explains. “I was planning to go abroad after school, but suddenly I was at an academic disadvantage.”

Today, as a teacher, she wants to help the young girls in her care understand the challenges of early pregnancy.

Says Jaquire: “The children don’t realise what they’re giving up. They almost take pregnancy and childbirth for granted. What bothers me in Hopetown is that, when I speak to parents, it’s become normal for them.”

*Not her real name

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.