Insecure tenure: Mara Ratshosa says she no longer feels welcome at Wilton Valley farm, where she has lived and raised her children since the 1950s. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

Voices from the farms: Part one of a three-part series focused on the lives, challenges and needs of farm dwellers, their relationship with the land and those who own it

Details contained in an application for a protection order against the manager of a luxury game farm in Limpopo paint a grim picture of circumstances that have seen farm dweller Isaac Pukuni flee from his home, fearing for his life.

“All my items are at home [the farm]. I can’t reach them. I’m afraid my life is at risk. I can’t even change my clothes; my ID — everything is there. He don’t treat me like a human being,” Pukuni wrote in the statement.

The Lephalale magistrate’s court dismissed his application for a protection order against Johan de Jager of Wilton Valley Hunting Safaris on 22 September because the “action [as reported by Pukuni] do [sic] not constitute harassment.”

Wilton Valley Hunting Safaris is described on its website as “the pride of Southern Africa’s hunting establishment. Hunters over the world testify to the high standard of the hunting safaris at Wilton Valley.”

Wilton Valley. (Lucas Ledwaba)

Wilton Valley. (Lucas Ledwaba)

In his application, Pukuni wrote that De Jager, accompanied by another person, threatened him with a firearm, ordering him to leave the property where he was born 35 years ago and where his grandmother and other extended family members still live. He says the alleged harassment has been ongoing since 2013.

He also accused De Jager of shooting and killing the family’s poultry and ordering him to leave the farm, despite not having a court order to that effect. “He chased away my stepfather [Elias Moatshe]; [he] shot our chickens and insulted us. He is insisting that I should leave, but I am insisting I was born here. I am not going anywhere,” he says.

The Mail & Guardian sent detailed questions to De Jager two weeks ago, but he has failed to respond.

Pukuni has reported the alleged intimidation to the police and the departments of rural development and social development.

On 26 March, the department of rural development’s land unit officer, Phuti Morema, wrote to De Jager inquiring about Pukuni’s complaint.

Farm dweller Isaac Pukuni is living in fear of property owner Johan de Jager against whom he has opened a case of intimidation. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

Farm dweller Isaac Pukuni is living in fear of property owner Johan de Jager against whom he has opened a case of intimidation. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

In the email, Morema informs De Jager that the family reported they were being threatened with eviction and that their privacy was being violated “by the farm owner”.

He also raised the issue of the threat to evict Moatshe, Pukuni’s stepfather, who was employed on the farm.

Morema’s email suggested a meeting between all parties and pointed out the department’s attitude in such matters was often to resolve the issues mutually, without resorting to legal battles.

De Jager declined the proposed meeting in an email dated 16 June, which followed other correspondence after the initial email by Morema.

“I have difficulty in finding any reason for us to meet,” De Jager responded.

He went on to say that Pukuni “is not, and has never been an employee on the farm. He returned as a married adult with his wife and children in 2013, only because we employed his father [Moatshe]. We have from the outset informed him that his stay on the farm is not acceptable.”

De Jager asked why “is it expected from farm management to meet about a person that is not, and never has been employed, or had any right to be on the farm?”

“He has no reason to be on the farm,” he added.

But Pukuni disagrees and insists he has every right to be on the property, which he says is his only home.

In his correspondence with the department, De Jager accused Pukuni of stealing diesel and connecting electricity illegally. But Pukuni denied this, questioning why, if this were the case, De Jager has never opened cases with the police.

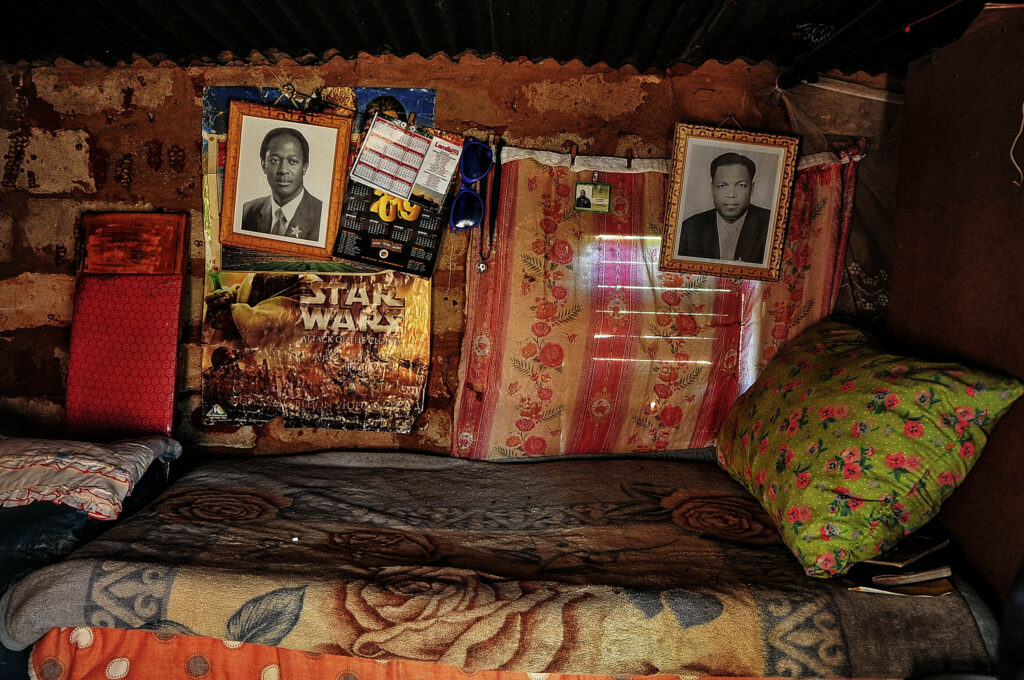

Isaac Pukuni’s bedroom at Walton Valley farm in Bultfontein near Botswana. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

Isaac Pukuni’s bedroom at Walton Valley farm in Bultfontein near Botswana. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

The dismissal of Pukuni’s application by the court raises questions about the willingness of courts and police to investigate and prosecute cases brought by farm dwellers and farmworkers against farmers, a factor detailed in a report into conditions on farming communities by the South African Human Rights Commission (SAHRC).

The August 2003 report — titled Inquiry into Human Rights Violations in Farming Communities — found that the state provided minimal legal assistance to farming communities in such instances. Although there are adequate laws, which are even-handed, “those who have resources use the law as a tool”.

The report also noted that farming communities are characterised by an acute lack of awareness of human rights, and a lack of training and education about rights and mechanisms to enforce rights. It also noted critically that there existed “skewed power dynamics between farm dwellers and farm owners”.

A follow-up report by the SAHRC in 2008 found that: “There remain incidences and pockets of serious human rights abuse where employers and persons in charge infringe the rights of workers and farm dwellers.”

There have not been any other such investigations undertaken by state organs or related bodies since the 2008 SAHRC report.

The Economic Freedom Fighters recently put forward a motion in parliament calling for the establishment of an ad hoc committee to investigate the living and working conditions of farmworkers and residents in the country.

The ANC, however, proposed an amendment saying that the issue should be dealt with by the parliamentary portfolio committees of labour and employment, together with the rural development and land reform portfolio committee.

Although the wheels of justice had seemingly come to a standstill in this case until our inquiry to the National Prosecuting Authority, Pukuni is now squatting with extended family in the shack settlement of Lesedi near the farming village of Steenbokpan.

The village — located between the town of Lephalale and the Limpopo River, which marks the border with Botswana — is one of the most remote areas in South Africa and home to a thriving game- and cattle-farming industry.

The shack settlement, located about 35km west of the Medupi power station, is reputed to be a relic of a wave of eviction of farm dwellers and workers that swept across rural South Africa in the early 2000s.

A 2005 study by Marc Wegerif of the land rights movement Nkuzi Development Association noted that more than one million farm dwellers had been evicted from farms since 1994, most of them illegally.

Pukuni says he was born in Wilton Valley in 1985, a fact supported by his maternal grandmother, Mara Ratshosa. His mother, Dora Pukuni, was also born there in 1967. Ratshosa says she started living on the farm with her now late husband Robert Pukuni as labourers in the mid-1950s. Their first child, Paulson Pukuni, was born on the farm in 1959. Their nine other children were also born there.

Paulson Pukuni. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

Paulson Pukuni. (Photo: Lucas Ledwaba)

Ratshosa’s husband died in a road accident in 1992. She remained on the farm, working as a domestic until she retired because of old age and poor health. She raised Pukuni on the farm, while his mother, who also initially worked there as a labourer, later left to seek domestic work outside the farm.

Ratshosa says she and her husband worked for Johan de Jager’s father Hennie de Jager from the 1950s until he died in or around 2013.

“Things were better back then, but now there are too many problems. Right now, the farmer [Johan de Jager] provides us with salty water. We never used to drink salty water,” says Ratshosa.

Hennie de Jager died in 2013. His son, Johan de Jager, who according to Pukuni and Ratshosa did not live on the farm before, took over the running of the business and the property.

“In my view, I think this man [Johan de Jager] wants to kick me out of the farm, but he doesn’t know how to,” Ratshosa says when asked if she feels safe on the property.

Pukuni says that since Hennie de Jager’s death his son Johan has been harassing the family in an alleged bid to kick him off the property.

“Johan De Jager comes into our house attacking us [verbally], opening doors and telling us this is his farm [and] he will do anything and he doesn’t want us [there] anymore,” Pukuni says.

In 1997, parliament passed the Extension of Security Act “to provide for measures with state assistance to facilitate long-term security of land tenure”.

The Act sought to protect the tenure rights of farm dwellers and to stop the arbitrary evictions that were often carried out without valid court orders.

Under the Extension of Security Act, Ratshosa is recognised as a long-term occupier and enjoys special rights, because she has lived on the property for more than 10 years, is over 60 years of age and cannot provide labour to the landowner, because of ill health.

Her homestead includes an earth-built house that serves as a kitchen and another two-room structure, which serves as Isaac’s bedroom. The family erected these buildings, and this is where Ratshosa and her late husband’s 11 children were born and raised.

Ratshosa now lives in a two-bedroom brick house facing the two old structures. Hennie de Jager built the township matchbox-style home.

But it’s now in a bad state, with cracked walls that have holes through which insects and reptiles get into the house.

The house is not connected to a water supply. Ratshosa uses a pit toilet some distance from the house.

“The house is falling apart. I almost got bitten by a snake one time when I went to the toilet. I found it sitting on top of the toilet. I sometimes lose my way to the toilet because I can’t see properly,” she says.

The M&G asked De Jager whether he knew about the case opened by Pukuni against him relating to allegations of harassment and why he wanted him off the property.

He was also asked if he had previously opened any criminal case against Pukuni and whether the family has in any way, or at any other time, threatened his safety and security. He did not respond.

Mashudu Magada, the spokesperson for the department of rural development and land reform in Limpopo, has also for weeks failed to respond to questions.

Pukuni, meanwhile, continues to live in fear and wonders if he will ever return to the only home he knows to live in peace.

“We have no freedom. We can’t go anywhere. We are like chickens,” he says. — Mukurukuru Media