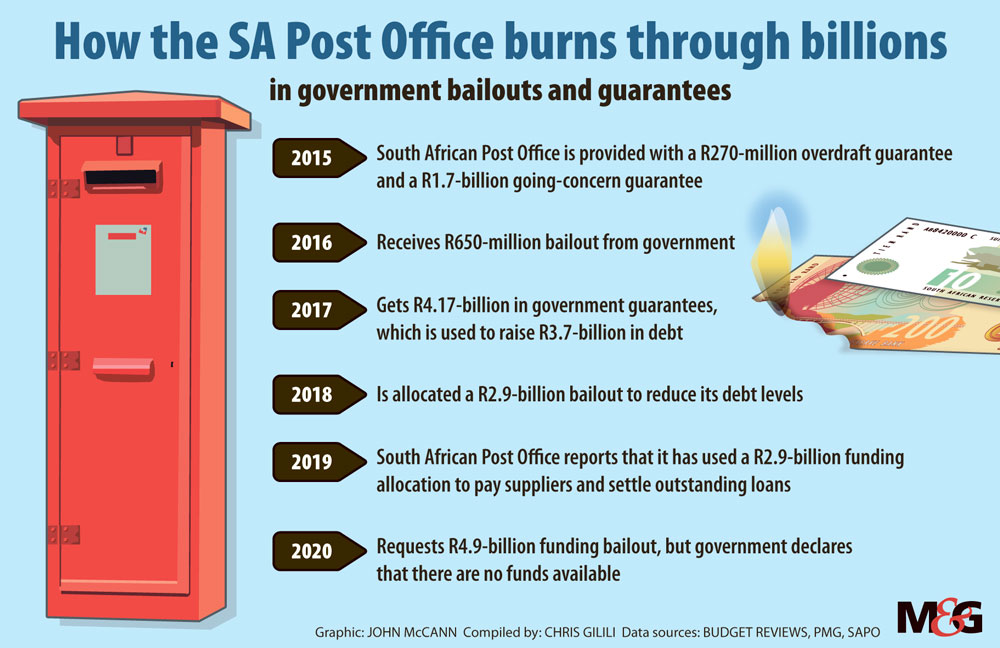

Over the past decade, the South African Post Office has had significant business problems, including debt to creditors and poor revenue collection.

The South African Post Office (Sapo) has failed since April last year to pay R842-million to the pension fund and medical aid of its more than 16 000 employees.

Sapo spokesperson Johan Kruger confirmed the amount with the Mail & Guardian, and added that the organisation was negotiating payment terms.

“The post office decided to pay employees their take-home salaries, whilst engaging the pension fund and medical aid service providers on payment arrangements. The company has made partial payments towards the outstanding amounts and remains in discussions with these service providers regarding payment terms,” said Kruger.

It is understood that the partial payments referred to are for general debts.

Kruger continued: “The liabilities of the SA Post Office exceed its assets which means that it is technically insolvent, however the Post Office has various initiatives intended to improve its financial standing, including the application for the Covid-19 relief funding from government.”

Auditor general Tsakani Maluleke revealed in April that the state-owned enterprise has debt amounting to R5-billion and is “commercially insolvent”. Sapo said last year that decreasing revenue and the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic were the main reasons for its financial woes.

Communication Workers Union secretary-general Aubry Tshabalala told the M&G that some workers had informed the union that they were “frustrated” because when they sought medical attention, they had to contend with unpaid schemes.

“We were so cautious and got shocked to learn that these statutory benefits appeared on workers’ payslips yet they were not paid to the relevant service providers. This places the social welfare of workers in a bad space,” he said.

According to Tshabalala, the union had called for a probe of Sapo’s finances before the findings by the auditor general.

“We further said on the question of human capital we called on human resources to audit and investigate if there are ghost workers. We are now at some comfort, having seen the post office initiating this process under the new group chief executive. But we are cautious that we were not officially briefed on the matter,” said Tshabalala.

There is growing concern about a possible liquidation of the entity should it not be repurposed.

Sapo appointed a new chief executive, Nomkhitha Mona, in February, following the exit of Khathutshelo Ramukumba, who spent only three months at the helm. Sapo appointed a new chief executive, Nomkhitha Mona, in February, following the exit of Khathutshelo Ramukumba, who spent only three months as CFO of the post office. On Wednesday, Mona told parliament that the organisation had 80 branches left to close around the country, to reach its target of 130 closures.

A Sapo source who spoke to the M&G on condition of anonymity, said there had been “a lot of unfair labour practices occurring at Sapo”.

“Even the chief executive who only resigned after three months in charge … he saw the burden hence he resigned. We haven’t paid the employee pension fund for about a year now. We owe the pension fund and Medipos an amount close to R1-billion,” said the source.

“Staff morale is at its lowest at the post office, because executives don’t address the root cause of the problems. They focus on protecting themselves first. Sapo owes millions to stakeholders and service providers as well,” said the source.

Communications and digital technologies minister Stella-Ndabeni Abrahams earlier this month announced during a committee meeting that a team of experts would be appointed to develop a strategic turnaround plan for the entity.

The intervention would be at the shareholder’s (government’s) cost and would include restructuring.

“The post office remains in ongoing discussions with the government regarding funding. There is acknowledgement from the government that the post office would require financial support due to the separation of the Postbank without compensation,” Kruger said.

Last week, Sapo re-launched legal action against PostNet and the SA Express Parcel Association. The action is aimed at enabling Sapo to be the only courier operator that can deliver packages weighing 1kg and less.

Sapo’s legal action is backed by the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (Icasa).

According to Democratic Alliance communications spokesperson Cameron Mackenzie, Sapo is beyond repair.

“I have raised the issue of the pension fund non-payment for a number of times. They don’t have answers simply because they don’t have money. For the financial year ended in March 2021, over R2-billion in loss was recorded by the post office. They are trading insolvently, which is a crime. Since 2014, the entity has been losing money instead of making any,” said Mackenzie.

He said talk of turnaround strategies was not new.

“We have had a lot of these turnaround strategies, they never work afterwards. They promised us an e-commerce mall, which failed dismally. Why not go into business rescue if the entity is struggling? I personally think instead of blocking other companies who are good in this courier sector, they should give them space,” said Mackenzie.

Earlier this month, Sapo said it wanted to be compensated for its investment in Postbank.

Mackenzie said that even this would not do much to ease its debt load.

“I think they have invested probably around R3.5 billion in Postbank, meaning all of their compensation will just go towards paying some of their already accumulating debt. They have a history of not paying their rent in different parts of the country,” Mackenzie said.