Voting for Vearey: A silent protest was held in Cape Town for dismissed top cop Jeremy Vearey. (David Harrison/M&G)

The setting for the arbitration hearing at which Jeremy Vearey, the controversial former Western Cape police deputy commissioner and head of detectives, is challenging his May dismissal from the South African Police Service is the marble-floored, four-star Cullinan hotel in Cape Town.

The opulent venue seems an oddly fitting arena for the at times heated exchanges between witnesses and counsel for Vearey, contrasting with the bonhomie on display at snack time or on the steps outside.

Vearey’s pentimento moment came at the beginning of his testimony when he cast light on the faultlines in the police service. But instead of peeling away the present to get to the past, he started with the past, revealing that he “was a directive member and part of the [Western Cape] provincial leadership responsible for covert operations of the ANC’s department of intelligence and security”.

He was recruited in 1983 to join the ANC’s underground military structure, Umkhonto weSizwe, alongside his trusted colleague, Peter Jacobs.

Jacobs, the former Western Cape and then national crime intelligence chief, was also at the hearing.

Vearey and Jacobs served time on Robben Island after they were arrested under the Internal Security Act for terrorism in 1987. In April 1995, Vearey joined the police where there were “all the signs of ill omen”, he writes in his book, Into Dark Waters, A Police Memoir.

“The new force was a Franken-stein’s monster, a patchwork of the old South African Police and 10 homeland police forces; a Babel of 11 separate police statutes, communicating in 11 different languages; and with a separate but unequal distribution of assets and resources,” he wrote.

Vearey was appointed assistant provincial commander for internal security in the Western Cape in 1995.

In 1996, he became a police gang expert, a position he describes as “where the politics of organised crime became my new enemy”. More than a decade later, he headed up Operation Combat, an anti-gang strategy unit in the Western Cape.

Vearey described his involvement in uncovering what later came to be known as “guns to gangs”. His legal team argues, it was his involvement in this that is the key factor driving a strategy in the top echelons of the police to get rid of him and Jacobs.

In 2013, Vearey’s team followed leads about police service and defence force weapons being sold to gangs on the Cape Flats. Subsequently, he said, Z88 police pistols, LM6 semi-automatics and AK47 assault rifles were confiscated from gangs. Project Impi was launched in 2014 as an “extension of Operation Combat”.

The collaboration between Vearey, as head of detectives, and Jacobs, as the crime intelligence head in the Western Cape, led to the arrest of the provincial head of firearms control in Gauteng, Chris Prinsloo.

Prinsloo confessed to selling more than 2 000 guns, earmarked for destruction, to criminals in the Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal and the Western Cape, and was sentenced to 46 years in jail, reduced to 18 years provided he helped the police identify more senior officers involved in the illegal sale of firearms. He was released on parole in 2020 after serving less than five years.

Former firearms control head in Gauteng, Christiaan Prinsloo, was found guilty of selling more than 2 000 guns to criminals in the Western Cape, Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal. (Image: Die Burger)

Former firearms control head in Gauteng, Christiaan Prinsloo, was found guilty of selling more than 2 000 guns to criminals in the Western Cape, Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal. (Image: Die Burger)

Vearey argued during his arbitration hearing that Prinsloo’s arrest resulted in his and Jacobs’ removal from their provincial posts.

They challenged their transfers in the labour court, but the matter was set aside with costs in August 2017. Operation Combat was disbanded and its members transferred.

Vearey and Jacobs were reinstated when Cyril Ramaphosa became head of state in 2018.

Jacobs, who became the head of the police inspectorate in May this year, was suspended in November last year along with five other officials for their alleged involvement in a R1.5-million procurement bid for Covid-19 personal protective equipment. The Hawks are investigating the matter.

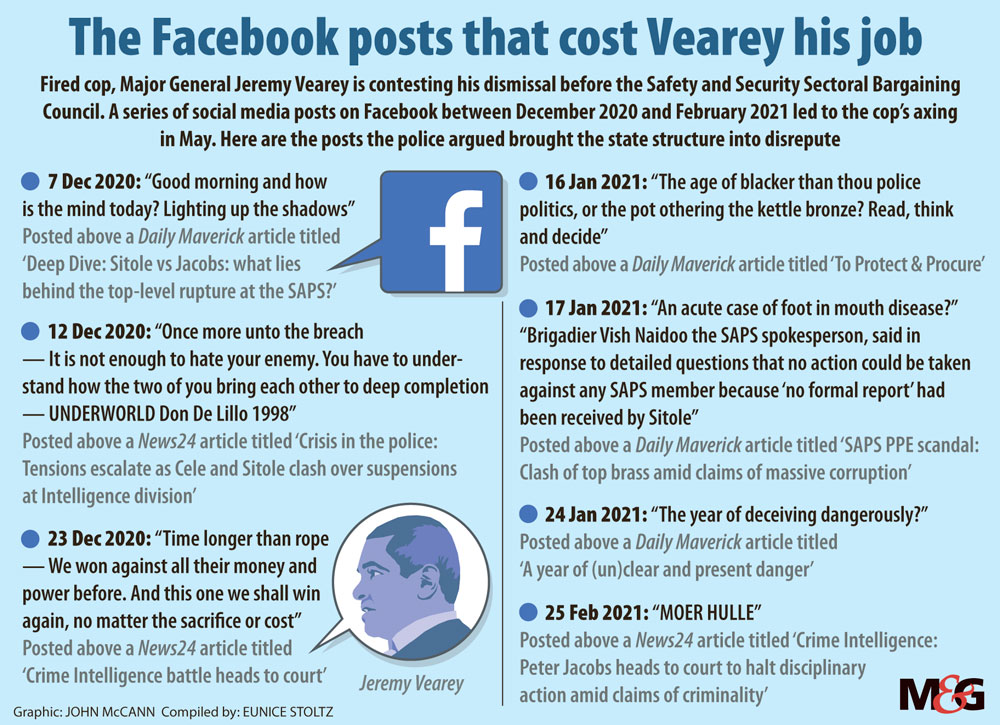

Vearey was dismissed from his position as deputy commissioner and detective head in the Western Cape after he was found guilty of bringing the police into disrepute with eight Facebook posts between December 2020 and February 2021, which contained links to media reports, most of which referred to the disciplinary charges against Jacobs.

Johann Nortje, representing Vearey, stressed the narrative about an ongoing strategy in the top ranks of the police to get rid of Vearey and Jacobs as a result of Project Impi.

Both state witnesses at the hearing, Limpopo deputy police commissioner Major General Jan Scheepers and Eastern Cape police commissioner Lieutenant General Liziwe Ntshinga, denied there was a plan to get rid of Vearey and Jacobs.

Scheepers and Ntshinga were appointed by the national police commissioner, Khehla Sitole, who signed off on Vearey’s final dismissal.

Guy Lamb, of the political science department at Stellenbosch University, says “certain elements within the police leadership” would want to get rid of Vearey and Jacobs.

“They are quite different to many others within leadership positions, and because they speak their minds and they’re critical. It doesn’t sit well with the kind of militarised hierarchical approach within the police,” says Lamb. “Spurious reasons are being used to sideline them, silence them and remove them from the police.”

He describes the targeting of Vearey and Jacobs as an “orchestrated strategy” and that efforts to get rid of the two “go back to Project Impi and it has to do with a lot of very [key] questions that they have been asking and evidence they uncovered, which implicates some very senior people not only within the police, but also within their advising [panel]”.

Pieter Groenewald, the leader of the Freedom Front Plus, in his capacity as an MP on the police portfolio committee, is cautious as he argues: “Should they have evidence of corruption relating to the firearms project, information could have found its way to the media through a whistleblower a long time ago.”

Lamb upholds that a “culture of secrecy” reigns in the police, where no one asks questions and no one criticises the leaders. “You kind of hold the line, even if the leadership is incompetent, even if the leadership is problematic.” He sees the arbitration of Vearey’s dismissal as a “critical case for the future health of the police. But if nothing is dealt with, then it’s going to be a continued slow decline of public trust in the police and police professionalism.”

But the constant battles between the police and Vearey and Jacobs are just one layer of the painting tarnishing the image of the police service. The real fight is happening at the very top between Sitole and Police Minister Bheki Cele.

Groenewald argues that Vearey and Jacobs are exploiting the battles between the two top cops.

“This is the perfect example where the commissioner and the minister are in conflict with each other and it is being abused by employees, in this case senior management,” he said.

The Mail & Guardian previously reported that the rift between Cele and Sitole became public in May this year when Cele sent Sitole a scathing letter, calling him “irresponsible”.

The letter fuelled criticism that Cele was meddling in operational matters and usurping Sitole’s powers because he ordered Sitole to reverse nine senior appointments. The tension between the two was evident during the arson, violence and looting that hit parts of Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal in July, and again in accusations of Cele interfering in and stalling the restructuring of the service.

Lamb argues that “there is a senior level [in the police service] that is quite dysfunctional,” adding that the “ongoing conflict between the national commissioner and the minister of police is probably the key defining problem at the moment — and it really is a political problem and it requires a political solution”.