President Cyril Ramaphosa. (GCIS)

In papers filed in reply to a constitutional challenge on load-shedding, president Cyril Ramaphosa has said that it does not constitute a dereliction of duty on his part or that of national government as the law places the responsibility for electricity provision on municipalities.

The president is opposing the application filed by 19 litigants, including opposition parties, in his own capacity and on behalf of the government, cited as the eighth respondent.

In his answering affidavit, Ramaphosa argued that in terms of part B of schedule 4 to the Constitution, electricity and gas reticulation is a competence of local government.

And since there is nothing in the Constitution or any other law that compelled him to provide electricity to the public, he could not be accused of failing to uphold the Constitution because the lights are not staying on.

“It is now accepted that municipalities are in law required to provide water and electricity to their people as a matter of public duty,” Ramaphosa said.

“This duty does not lie with the president or any of the national departments cited herein as respondents.”

Ramaphosa said the Constitution does not prescribe what consequences must flow from the president upholding the Constitution, as section 83 enjoins him to do, and nor can the court prescribe what those must be.

[related_posts_sc article_id=”540831″]

“The mere fact that the president’s best efforts may not have produced the results desired by the applicants in this case does not mean that the president has ‘failed to uphold, defend and respect the constitution as the supreme law of the republic’ as suggested by the applicants’.”

The law gave him no authority to perform or interfere in the executive functions of municipalities, Ramaphosa added.

“Accordingly, if municipalities do not for one reason or another supply electricity to their people, the constitution does not say that the president must go down to local government and do it.”

But the fact that electricity provision was the domain of municipalities, did not mean that the applicants had made out a case against this sphere of government, he said.

[related_posts_sc article_id=”538495″]

Section 4 of the Municipal Systems Act of 2000 provides that municipal councils had a duty to give members of a community “equitable access to the municipal services to which they are entitled”. But this could only apply to electricity as far as it was available.

“If there is no electricity available for one reason or another, equitable access is impossible. The applicants have not made out a case to demonstrate that municipalities have failed to provide equitable access to their people.”

Hence, Ramaphosa said, the applicants cannot sustain their claim that rights promised in the Bill of Rights were violated on an ongoing basis. He also noted that section 152 of the Constitution qualified that municipalities must strive to achieve their obligations within their “financial and administrative capacity”.

[related_posts_sc article_id=”538564″]

“Municipalities do not have the necessary capacity to supply electricity in circumstances where Eskom has determined that load-shedding must be implemented.”

The applicants have asked the court for a declaratory order that Ramaphosa, Eskom, Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan, Mineral Resources and Energy Minister Gwede Mantashe and the state as a whole have contravened their obligation to protect, respect and promote the rights enshrined in the Bill of Rights.

Their application is in two parts.

In the first, they seek an urgent interdict compelling the state to exempt certain sectors from load-shedding to ensure the provision of basic services, including health care, education, policing, water and sanitation.

The parties also ask that the government be ordered to table a plan, within seven days, with steps it will take to end load-shedding, including a maintenance schedule for Eskom.

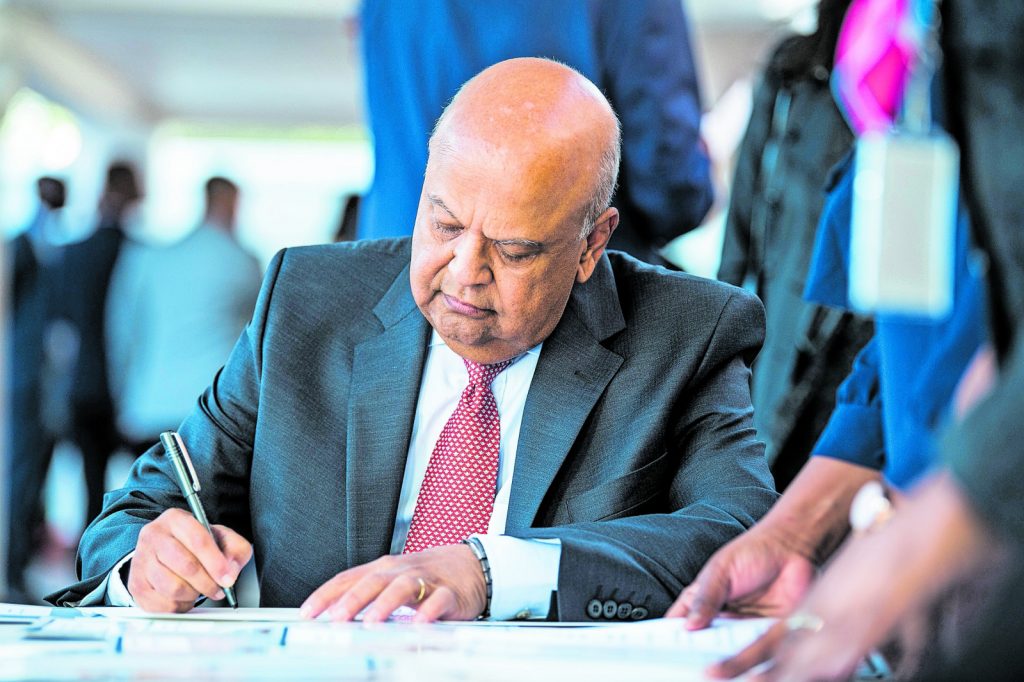

In hot water: Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

In hot water: Public Enterprises Minister Pravin Gordhan. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Ramaphosa warned that since load-shedding was implemented to prevent the power grid from collapsing, the court should think carefully about granting an interdict that would compel the state to ensure constant power supply to some sectors pending the hearing of the second part of their application.

“The whole of the republic, and not only a few institutions and facilities, stand to suffer more harm if the interim relief is granted than the applicants would suffer if the interim relief is not granted,” he said.

“This is more so due to the fact that there is serious risk of the electricity grid collapsing to a state of a total shutdown if load-shedding is not implemented in the manner in which it is currently being implemented, ie. In which all sectors of society are switched off from time to time.”

The relief sought was not practical as it would take longer to identify all those institutions, including small businesses scattered around the country, that the applicants want to benefit from the interim interdict, than for the second part of their case to come for the court.

But it was also not competent, Ramaphosa said, because the applicants are asking that the minister of public enterprises tell municipalities to shield certain groups from load-shedding and by law he could not. It would mean dictating to another sphere of government and there was no legal basis for the minister to do so.

No energy: Minister Gwede Mantashe. (Delwyn Verasamy, M&G)

No energy: Minister Gwede Mantashe. (Delwyn Verasamy, M&G)“Municipalities are the local sphere of government and cannot, without a constitutional basis, be told by the DPE as to who should and who should not be switched off and when.

“Similarly this court cannot without a constitutional basis direct the DPE to instruct another sphere of government who to switch off and when to switch them off.”

Ramaphosa noted that the applicants have not joined municipalities as respondents in the matter and said without this, the relief cannot be granted as they were not afforded a chance to be heard.

He raised the further point that the department of public enterprises did not decide whether or when load-shedding was implemented.

Therefore, if the court were to order the department to ensure that municipalities exempt certain sectors from load-shedding, it would in practical terms mean that Eskom should alert it beforehand.

“There is no legal basis for Eskom to do this.”

The first part of the application will be heard by the Pretoria high court on 20 March and the second part on 23 May.

Ramaphosa argued that no right would be irreparably harmed between the first date and the second, and that therefore there was no need for interim relief.

“The position of the applicants is not going to get worse than it is at the moment to justify the drastic interim relief which they seek when it is only likely to be in operation for a few weeks.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)Their position would not deteriorate, Ramaphosa said, because of the “active and deliberate steps” the government continued to take to curtail load-shedding.

The applicants include the United Democratic Movement (UDM), Build One South Africa, the Inkatha Freedom Party, the National Union of Metalworkers of South Africa, the African Council of Hawkers and Informal Business, the Soweto Action Committee, the White River Neighbourhood Watch and political analyst Lukhona Mnguni.

UDM leader Bantu Holomisa in a founding affidavit suggested there was an apparent contradiction between the explanations given for the crisis – and the solutions advocated – by Gordhan and Mantashe.

Ramaphosa denied this, saying it was necessary both to build new power plants and to maintain existing ones and the ministers knew that these steps were not mutually exclusive.

“The actions which have been taken by the two departments during this administration demonstrate a clear understanding of the roles and responsibilities of each.”

He said he was leaving it to Eskom, which is cited as the first respondent in the matter, to provide finer detail as to the causes of load-shedding but listed six factors, including a lack of funding for maintenance and “sabotage, theft and corruption at power stations.”