It’s business as usual for South Africa’s farmers, who are still disproportionately represented by white Afrikaners, but who are not taking up refugee offers anytime soon. (Photo by Jamie McDonald/Getty Images)

South African farmers are not rushing to flee “land grabs” and relocate to the US to take advantage of President Donald Trump’s controversial executive order that offered them refugee status last week.

Instead, some farmers view Trump’s executive order cutting aid to South Africa and extending asylum in the US to white Afrikaans farmers “who are victims of unjust racial discrimination” with suspicion, wondering exactly what his motivation may be and lamenting that he has stirred up racial tensions.

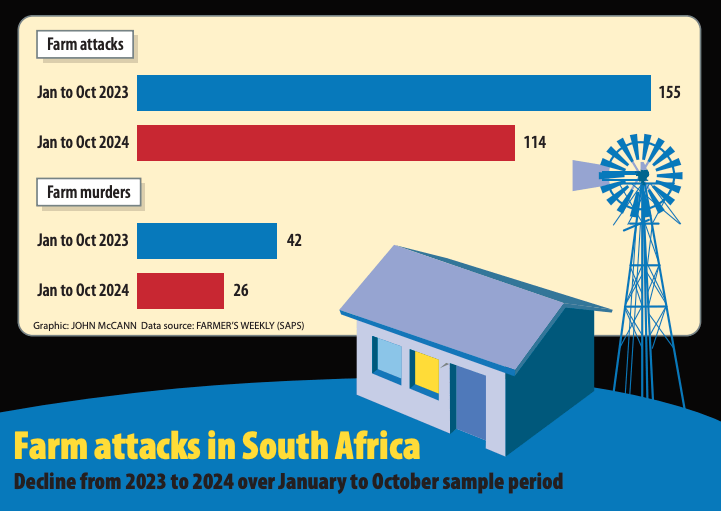

Several farmers from the Eastern Cape, Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal who spoke to the Mail & Guardian about their feelings regarding the order precipitated by President Cyril Ramaphosa signing the Expropriation Act into law last month, as well as the high number of murders and assaults on farms, said they have no intention of leaving South Africa.

Their concerns about the Act ranged from worry that it could in future be used to expropriate land without payment under the “nil compensation” clause, which allows the government to do so if it is in “the public interest”, to believing that the law is “unlawful” and that it can be challenged constitutionally.

But the Expropriation Act is not part of South Africa’s land reform regime; it is designed to enable the state to acquire a specific property from a private owner to fulfil a public function. The scope of the Act is limited because only the department of public works is empowered to expropriate property in this context.

Eastern Cape farmer Riaan Ardendorf, 43, who keeps cattle and sheep and grows soya and sunflowers, was sceptical about Trump’s asylum offer, saying he has financial and familial commitments that tie him to South Africa. He added that he lives peacefully with his Xhosa neighbours who are also farmers and has no intention of leaving.

“I’m an eleventh-generation farmer. My family’s been here for forever. We come from Dutch and German descent,” Ardendorf said.

“We can’t go. I’ve got a mum and dad who are now old, and they can’t just pick up and leave. We’ve got commitments to the banks. If everybody picks up and leaves, who is going to buy land? How are you going to settle your debts with the banks because the banks are not interested in those laws? They don’t care about this Expropriation Act.”

Ardendorf said farmers could not just “walk into America and buy a farm” and would have to take other jobs. “You are going to pay for living expenses there and pay your debts here? If I don’t pay this farm off my dad’s house stands surety for me,” he said.

Crime

Regarding crime, he said his deep rural farm is not easy to access because of poor roads, a problem farmer unions often raise with the government because it makes it difficult to get products to market.

“The crime is a hell of a lot worse for those farmers, guys that have got easier access to their properties via road networks where guys can drive with any type of vehicle. They are more in the firing line than guys like me, who are extremely remote, where it’s 4X4 only because the road hasn’t been great in 22 years,” he said.

However, he said he could not help wondering whether Trump knew something about what might lie ahead down the road for farmers.

“We don’t know what Trump’s angle is and what information he’s working off, and that’s our biggest worry at the moment …We don’t know what Trump has got …What does he know is coming?

In KwaZulu-Natal, a farmer who asked to remain anonymous said he had, under duress, sold his farm in the Midlands to the provincial department of agriculture and rural development 12 years ago.

“One of the other farmers said ‘no’ and he was taken out two months later, killed, shot twice in the back of the head. Nothing was stolen,” he said. “So, when your family starts to put pressure on you, because they feel something similar might happen to you, your mindset changes … My staff were begging me not to sell. It was a two-year nightmare.”

The farm, which he had rehabilitated from scratch after buying it, now lies derelict under government ownership, because it was never transferred into the names of his former workers.

“My head did not come around for three years. I went and farmed all over the place. I spent four years in Ethiopia and in South Sudan and then came back to South Africa after I swore blind I’d never come back. And it’s because it’s hard. It’s because we’ve got a connection to the people and to the land and to the language and to our customs and cultures,” he said.

Robin Barnsley, an egg farmer and former president of the KwaZulu-Natal Agricultural Union, said he is concerned about the Act, which he believes is “open to challenge” constitutionally.

But for him, it’s business as usual. Barnsley recently invested heavily in a new system to improve production efficiency and said many Afrikaans farmers are doing the same.

“I think that he [Trump] makes decisions built on arguments devoid of a reasonable factual basis. He doesn’t understand what he’s doing. I think he’s trying to talk consistently to the right wing in his country, and to the right wing globally,” he said.

“It would be nice to be able to disregard him, but you can’t because he’s a powerful man. He’s exceptionally dangerous because he’s creating risk for the world economy more than expropriation without compensation is creating risk for us.

“Representative bodies for Afrikaners have all distanced themselves from [Trump’s offer], which says to me he hasn’t got his facts right. I associate with a lot of very young, very astute Afrikaans farmers, and they are investing significantly. They haven’t held back. They might lament what’s going on around the pub, but they carry on with what is in their best financial interest,” he said.

Western Cape wheat, barley, canola and Black Angus cattle farmer Derek du Toit, 31, believes the Act is merely an attempt by President Cyril Ramaphosa’s ANC to garner votes but trusts the policy will not be fully implemented.

“They are in decline. They’re in big trouble. They’re going to extremes to try and win the popular vote. They’re not doing it for the people,” he said. “It’s a selfish attempt to remain in power because it’s a popular idea, you get land for free for the majority.”

South Africa is one of few countries in the region with “proper food security and that is thanks to the farmers”, Du Toit said.

“We are working hard. We make a living, and we make do with what we’ve got. It’s not that we get any assistance from the government at all. It’s quite the opposite. What they’re threatening to do, you’d think that Zimbabwe would be a cautionary tale. You’d think that they’d see, ‘Oh, maybe this is not such a good idea to take land and redistribute it’.

“It’s such a short-sighted idea. I believe it won’t be fully implemented. I want to believe that, I want to have hope in our country that it won’t fully happen, as it did in Zimbabwe, just because there’s still some sense alive in our government, and some humanity, not just an attempt to grab power or to remain in power,” he said.

He said Trump’s offer should be extended to all farmers because people of all backgrounds and races have been victims of farm attacks.

“This is the first time that a major political, outside figure, has reached out and said we are willing to help if the need arises,” Du Toit added.

He said South African farmers who have moved to the US and Canada have been successful in the past and that Trump’s motivation could in fact be a desire to lure good farmers rather than altruism.

While farmers might not be rushing to emigrate to the US, lawyers, doctors and other professionals are among the more than 20 000 people who, by Tuesday, had contacted the South African Chamber of Commerce in the United States of America through email and social media to inquire about moving.

The organisation said these inquiries probably represent about 50 000 to 70 000 people because many were inquiring on behalf of their families.

The chamber’s chief executive, Neil Diamond, speaking from his Washington, DC, office, said his email server had crashed this week because of the influx of 7 600 emailed inquiries for information about Trump’s executive order.

“Most are from Afrikaans folks and there were some from temporary agricultural visa workers that come to the US. Some of the emails were from professionals, people in the legal profession, the medical profession, and a lot of young people indicating that they would like to seek a new opportunity and a brighter future.”

Diamond said he was “pushing” the US state department and the US consulate in South Africa for further information because only the government could handle the asylum process. He expected that Washington would publish an email address to which people could direct inquiries within a week.