Dr Tamryn Frank, Researcher, University of the Western Cape; Lori Lake, Communication and Education Specialist, Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town; Gilbert Tshitaudzi, UNICEF Nutrition Manager; Christine Muhigana, Representative, UNICEF; Dr Chantell Witten, Senior Lecturer and Researcher, University of the Witwatersrand; Makoma Bopape, University of Limpopo; and Jane Badham, Managing Director, JB Consultancy.

Restricting the advertising of unhealthy foodstuffs is crucial for promoting healthier eating options

Economic disparities remain a primary obstacle to food security in South Africa, with many low-income individuals and families struggling to afford an adequate and balanced diet. The high cost of nutritious food coupled with rising living expenses poses a significant barrier to accessing quality food options. The lack of access to quality food greatly affects children, whose long-term development is often stunted by low-nutrition and ultra-processed diets. The R3337 draft regulations on food labelling and advertising foodstuff in South Africa — championed by UNICEF, the Children’s Institute, senior researchers from the University of the Witwatersrand, University of the Western Cape, Limpopo and others — are aimed at improving public health literacy by empowering consumers to choose healthier diets.

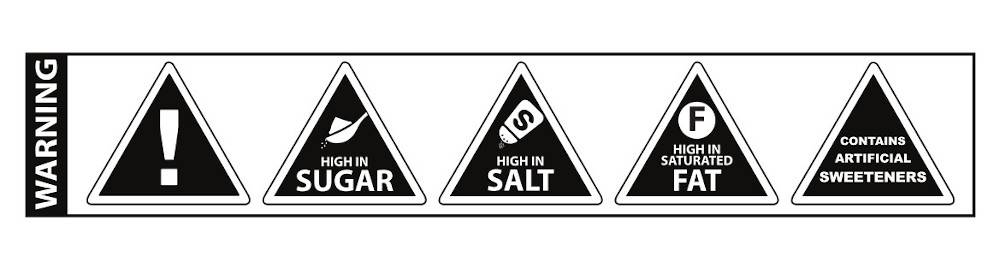

In South Africa, foodstuffs which exceed the nutrient cut-off values of the Nutrient Profile Model are required to carry a Front of Pack Nutrition Labelling (FOPL) in terms of draft regulation R3337. These foodstuffs shall carry a warning label complying with the specifications outlined in this picture.

In South Africa, foodstuffs which exceed the nutrient cut-off values of the Nutrient Profile Model are required to carry a Front of Pack Nutrition Labelling (FOPL) in terms of draft regulation R3337. These foodstuffs shall carry a warning label complying with the specifications outlined in this picture.

Regulating food labelling and advertising in South Africa

“Families and children across the spectrum live in a society that too easily promotes the consumption of unhealthy foods through easier access, cheaper costs and aggressive marketing. As UNICEF, we advocate for and support food labelling regulation that mandates consumer-friendly labelling to discourage the consumption of over-processed foods containing high amounts of sugar, salt, and saturated and trans fatty acids. Such labelling provides information that children and families deserve to know in order to make informed choices,” says Christine Muhigana, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) South Africa Representative.

Restricting the advertising of unhealthy foodstuffs will be crucial in promoting healthier eating options. This new regulation will put measures in place to guard against food companies advertising unhealthy foods to vulnerable people and children. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified the harmful impact of advertising unhealthy foods and advocates for regulations that limit the promotion of unhealthy products to children.

“Our immediate thought when we buy something sweet is to think of it as a treat. What we don’t see is the slow violence that is taking place in the child’s development. Consumers need to know that what tastes sweet is often detrimental to the wellbeing of children in the long term. We must think about who profits and who carries the costs of these cheap, unhealthy foods. Companies are making profits, but the people with diabetes and hypertension are the ones who suffer the most from these decisions,” says Lori Lake, Communication and Education Specialist, Children’s Institute, University of Cape Town.

Why labelling matters

Implementing consumer-friendly food labelling practices is important for promoting healthier food choices. The draft regulation R3337, released in 2023, builds upon previous regulations such as R146 (2010) and R429 (2014). This updated regulation suggests the inclusion of front-of-pack labelling aligned with WHO recommendations. The aim is to develop an evidenced-based nutrient profiling model that enables consumers to easily identify products high in nutrients of concern, such as sodium, total sugars and saturated fats.

To further aid consumers in making informed choices, the draft regulation emphasises the development of a warning label and a nutrient profiling model. The warning label could indicate whether a product is high in sugar, saturated salts or salt, or whether it contains artificial sweeteners. This visual cue aims to improve public health literacy and empower consumers to choose healthier options and identify ingredients contributing to the rise of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and obesity.

“The labelling will help people spend their money better and will also encourage corporations to sell nutritious and healthy products for people. Many people don’t have access to a quality food bucket, and companies must ensure that they make it easy for people to make nutritious options,” says Chantell Witten, Senior Researcher and Lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Not all the foods you can buy on our shop shelves are good for you. Proposed new regulations will ensure that the public knows more about what’s inside the wrappers of our foodstuffs.

Benefits of food labelling

Regarding the success of the Chilean method of nutritional profiling that has inspired the R3337 draft regulation, Frank says: “Children are learning from a young age that there are certain kinds of food that they should not be eating. Children are telling parents and caregivers that certain foods are not good for them and that they should not be buying those foods for them. They [Chileans] are seeing that manufacturers are reconsidering their production to make sure their foods have less salt and sugar.”

The health and wellbeing of children should take precedence over advertising and financial gains. The impact of childhood nutrition extends far beyond personal health, affecting the economy as children grow into adults. Regulating food labelling and advertising practices will ensure that consumers are provided with accurate information and are encouraged to make healthier choices.

Efforts to improve food labelling and advertising must also consider economic challenges and inequities in food access. Low-income areas often lack quality food options, making it difficult for people to make wise choices about what food they buy. The labelling system should encourage corporations to prioritise selling cheap, nutritious, healthy products. Additionally, enhancing public health literacy is crucial in helping individuals understand the impact of their food choices and in empowering them to make informed decisions.

Food insecurity and malnutrition in South Africa

Food insecurity is widespread in rural areas compared to urban centres, where limited access to infrastructure and resources hampers agricultural productivity and exacerbates food insecurity. However, in both urban and rural areas, there are many regions where access to quality food is limited or non-existent. They lack grocery stores or supermarkets that offer a diverse range of fresh and healthy food options. Instead, residents often rely on small convenience stores that stock processed and unhealthy foods. “The prevalence of obesity among children and adolescents in South Africa today requires our urgent attention and response,” says Muhigana.

“The marketing of these unhealthy and ultra-processed foods is tapping into our deep longings and are often targeted to children who are vulnerable to that marketing,” says Lake. The increasing movement of multinational corporations into South Africa, targeting children in remote areas, makes the issue of food and nutrition security worse.

“Seventy-six per cent of packaged food sold at supermarkets in South Africa is ultra-processed,” says Dr Tamryn Frank, a Researcher at the University of the Western Cape. There are more affordable options for ultra-processed foods than for healthy and good quality food, and they’re often cheaper.

Food and nutrition security means that children shouldn’t just have enough food to eat; we need to make sure they are not receiving “empty calories” and that they follow a balanced diet that empowers them. The food that children are sold and served right now are empty calories, with little nutrition,” says Muhigana.

The food industry should be held responsible for improving the nutritional quality of their products, rather than shifting blame onto consumers. “The food industry has done a fantastic job making it seem like most of why we eat badly is our fault. The food and beverage industry is the one that needs to be regulated to improve the food, rather than claim that we are the ones who need to change our behaviour. It is not you: it is the ultra-processed foods,” says Frank.

Regulating food labelling and advertising practices is essential for promoting healthier eating habits and combating the rising rates of obesity and non-communicable diseases. We need to address the inequities in food access, but it starts with enhancing public health literacy and holding corporations accountable for their role in promoting healthy nutrition. Only through collaborative efforts can South Africa ensure a healthier future for its children and pave the way for a more sustainable and ethical food industry.

— Welcome Mandla Lishivha