African states must embrace a strategy centred on resilience and self-reliance.

Sub-Saharan African states have gone into the African Growth and Opportunity Act (Agoa) summit in Johannesburg with a hope of negotiating improved trade agreements with — and excise-free exports to — the US.

They do so at a time when the continent has lost much of the cohesion and unity that existed at the time Agoa was signed and when new competition between the US and Russia — and more recently China — has put increased economic pressure on them to fall in line with either side.

Anthoni van Nieuwkerk, professor of international and diplomacy studies at the University of South Africa’s Thabo Mbeki African School of Public and International Affairs, said Africa had collectively lost much of the influence it had attained when Agoa was signed in 2000.

“When Thabo Mbeki was president he worked with a couple of other leaders to turn the Organisation of African Unity into the African Union. They launched the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (Nepad). They talked about the [African] Renaissance as the philosophical and ideological framework,” Van Nieuwkerk said.

This demonstration of the continent’s unity — and ability to put its house in order — allowed Mbeki and other leaders to approach the G7, the G20 and Western countries to negotiate trade pacts as equal partners, rather than seeking soft loans or free debt.

“On that basis he was accepted, because the West knew the guy meant business,” he said.

“We know the history since then. Nobody has replaced that energy and vision he had to say that Africa can be a rightful partner in multilateral international affairs.”

He said the African Union’s Vision 2063 — the continent’s development blueprint to achieve inclusive and sustainable socio-economic development over a 50-year period — was “very well written” but fell short when it came to implementation and was “not really going anywhere” as a result.

A number of factors in the intervening years had resulted in Africa failing to “grasp the moment and become a player on the international stage with confidence and dignity and standing tall”.

These included the Covid-19 pandemic, which came on the heels of a global economic collapse and increasing tension between the West and Russia, which had worsened since the annexation of Crimea in 2014 and ultimately resulted in the war in Ukraine.

A decline in US influence, combined with the rise of China as an economic, political and military superpower, had also resulted in the established rules for the diplomatic game “becoming unsettled, changing or being ignored”, Van Nieuwkerk said.

African states were being increasingly “sought after’’ by competing forces and were being “forced to take sides” through economic leveraging or the threat of sanctions, should they not fall in line with the positions taken by Western countries on international issues.

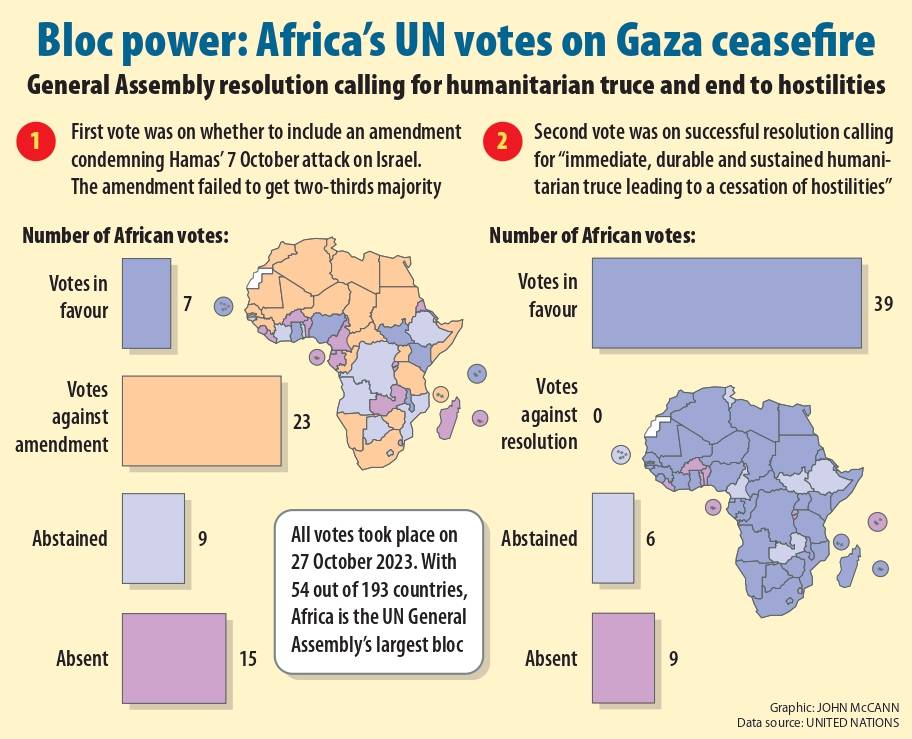

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

Agoa was taking place in this context, in a recalibrated international environment, in which a new cold war was turning increasingly violent and in which economic pressure on countries to take specific positions was increasing.

“Africa has been unable to position itself as a significant role player to influence any of these things. It has lost the moment,” Van Nieuwkerk said.

“Africa is not able to speak with one voice. The G20 accepting the AU as a member has been meaningless. The AU doesn’t have the ability to fight for the interests of the continent.”

The continent lacked unity and remained divided by history, colonialism and language, along with a lack of cohesion in collective regional diplomatic instruments.

Van Nieuwkerk suggested that instead of attempting to play a role on the international stage, the AU should “get its house in order” and focus on the conflicts on the continent first.

“Instead of flying to Ukraine to propose mediation, the AU should have stopped in Sudan, in South Sudan, in Mali, in the DRC and intervened first. Get your own house in order before going to Ukraine for mediation,” he said.

Until the AU found a way to cohere, to create continental stability and development, it would not have the ability — or the stature — to be able to talk business with the G20 as equals, he said.

The addition of more African states to Brics (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa) was positive — along with the potential further growth of the bloc — as it brought the potential of access to new economic opportunities through working with the member states.

This also brought the risk of an “uneasy alignment” between democracies, such as South Africa, Brazil and India, and countries such as Russia and China, and new entrants including Saudi Arabia and Ethiopia, which might sabotage the potential benefits of Brics for African countries.

Van Nieuwkerk said the show of unity at the UN by African states in the vote in favour of a ceasefire in Gaza — none voted against it — was an indication of unity but was tempered by the understanding of African countries having been the victims of the violence of colonialism and occupation themselves.

Israel maintained a strong economic presence on the continent, supplying a number of states with defence and security technology, and its influence, interest and power “cannot be underestimated”, he said.

Political analyst Sanusha Naidu come under growing pressure through trade forums in a bid to influence what stance they take on international issues such as Gaza and Ukraine.

Countries were being increasingly “courted” at a time when there was a lack of a continental identity, which was crucial if a common stance was to be taken in multilateral forums and would allow the continent leverage, if not the ability to influence outcomes, on international issues.

The vote by African states at the UN was “significant” and was likely to bring countries under more pressure at forums such as Agoa, a pressure which would increase as Israel moved to consolidate its interests in Africa at a time when the narrative was shifting against it internationally.

Against this backdrop, there was a need for the AU to be “far more coherent, cohesive and emboldened” in its stance for the continent to exert the level of influence it needed to further its common interests in multilateral forums.