A smoker buys a single cigarette at an undisclosed location after the government banned the purchase of tobacco products. Emmanuel Croset/AFP

SPONSORED

Covid-19 is on the rise, both in its incidence and distribution across all the provinces of South Africa. It has been stated repeatedly that Coronavirus is particularly dangerous for those with underlying health conditions, because it affects the respiratory system, causing breathing difficulties.

Smokers are one group of adults who are at particular risk if they catch the virus, and this was the underlying justification for the tobacco ban. However, many are questioning whether the ban is not in fact having the opposite effect of that intended. When the remedy is combined with poverty, a group for who Covid-19 poses a greater risk, and among whom smoking rates are disproportionately high, it appears the health risks are exacerbated rather than reduced.

One particular health vulnerability among the country’s most disadvantaged smokers is the all too common practice of sharing cigarettes. This behaviour, according to REEP, is becoming more common due to huge increase in the cost of cigarettes. This behaviour risks spreading the virus from person to person, according to a report by Sharon Cox, Senior Research Fellow, London South Bank University. Writing on BMJ Opinion, she explains: “The cigarette acts as a vessel for viruses, and the hand and mouth exposure means saliva and droplets can be easily and repeatedly taken from one smoker to the next. Similarly, smoking discarded cigarette ends, another behaviour which is common especially among the homeless population, risks exposing the smoker to infections.”

According to REEP, no less than “82% of respondents indicated that before lockdown, they never shared an individual cigarette with someone else”. However, during lockdown the percentage of smokers who never shared a cigarette decreased to 74%. “The number of people who indicated that they regularly shared individual cigarettes (more than 50% of cigarettes smoked were shared) increased from 1.7% to 8.9%, an increase of 430%.”

The authors argue that the intention of the sales ban, in terms of smokers quitting and reducing spreading Covid-19 through cigarette sharing, is undermined by the fact that so many people are still smoking cigarettes and by the increased occurrence of cigarette sharing. They conclude that the extension of the ban beyond lockdown level 5 has been misguided, and recommend that the ban be lifted immediately.

The online article by REEP states: “The sales ban has stimulated the already large illicit market. Illegal distribution channels have become more entrenched, which will have lasting public health and economic consequences. For every additional month that the sales ban continues, the government loses at least R1-billion in revenues.” [Note: In the series of articles on #Lift the Ban in Mail & Guardian last week, this figure was shown to be considerably understated, as not including VAT, lost PAYE and other tax shortfalls from the entire value chain.]

“The tobacco market has been destabilised. Manufacturers that were previously operating in the shadow of the multinationals have greatly increased their market share amongst the survey respondents. It seems likely that there will be a price war after the sales ban is lifted. The multinationals, with the support of their foreign-based principals, will want to regain some of their market share. Their local rivals, probably buoyed up by the profits earned over the lockdown period, will want to hold on to their new market share. In the absence of advertising and other conspicuous forms of marketing, prices are likely to drop below their pre-lockdown levels.”

Could the government have taken a different approach? According to Van Walbeek, “An alternative approach, which would have allowed the government to continue raising revenue, would have been to substantially increase the excise tax. Currently the excise tax is R17.40 for 20 cigarettes. If the government had doubled, or even tripled, the excise tax, it would substantially increase the price of tax-paid cigarettes, which would encourage smokers to quit or reduce consumption. The result would be similar to that of a sales ban, but the revenue would continue to flow to government and less would end up in the hands of the tobacco industry. More than a quarter of people who quit during lockdown indicated that they would start smoking again after the sales ban is lifted.”

Unintended consequences of the tobacco ban

New research by the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) of the University of Cape Town shows some of the many unintended consequences of the government’s ban on cigarette sales

Professor Corné van Walbeek, director of the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) at the University of Cape Town. (Photo: GTAC Winter School)

Professor Corné van Walbeek, director of the Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) at the University of Cape Town. (Photo: GTAC Winter School)Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) report called Lighting up the illicit market: Smokers’ responses to the cigarette sales ban in South Africa has found that the South African tobacco products market has changed immensely during the government’s ban. From being dominated by multinational companies — mainly British American Tobacco (BATSA) — it has evolved into a highly fragmented market dominated by brands manufactured by local/regional producers.

It further uncovered the extent to which the ban has created a boom in the informal retail sector, as formal retailers have apparently refrained from selling cigarettes, in line with government regulations. Smokers have tended to buy cigarettes from outlets such as spaza shops and street vendors, and through unusual platforms such as family and friends, WhatsApp groups and online, which have all grown in prominence, says the research report.

Between April 29 and May 11 2020, members of REEP conducted an online survey among smokers to determine how they responded to the ban on cigarette sales during the lockdown, and to evaluate how the lockdown has impacted the market for cigarettes in South Africa. The survey was completed by more than 16 000 respondents, and the final cleaned sample consisted of 12 204 responses.

The report, co-authored by Corné van Walbeek, Sam Filby and Kirsten van der Zee, showed one major public health gain: about 16% of the 12 204 respondents had successfully quit smoking cigarettes during the lockdown. However, states the report: “For the remaining smokers, we observed only a minor reduction in cigarette consumption per day. Around 90% of the non-quitting respondents had purchased cigarettes during the lockdown. The market for cigarettes changed considerably during the lockdown: the majority of smokers shifted brand.”

It continues: “The data suggest that the ban on cigarette sales is failing in what it set out to do. While a small proportion of smokers have been motivated to quit, most have continued to smoke and purchase cigarettes. The ban may well have undone the progress the South African Revenue Service had made in reducing illegal cigarettes prior to lockdown. It has given illicit traders a larger foothold in the cigarette market, and has created an opportunity for these traders to develop their distribution channels.”

On REEP’s website, the authors state: “Our report warns that the ban could be setting up an illicit market for survival well beyond the Coronavirus outbreak, and advises government to expeditiously lift the ban on the sale of tobacco products. We indicate in the report that the extension of the ban on tobacco sales as the country moved from Level 5 to Level 4 of the lockdown was an error. Extending the ban as the country moves from Level 4 to Level 3 perpetuates the error. After lifting the ban, government should strengthen its tobacco control policy to better align with the provisions of the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control and the Protocol to Eliminate Illicit Trade in Tobacco Products.”

Furthermore, the REEP research demonstrates how the average price of cigarettes has increased by nearly 250% compared to pre-lockdown levels. “Based on a second online survey, conducted between June 4 and 19 2020, REEP researchers found that the average price per cigarette was R5.69, or R114 per pack of 20. Some respondents reported prices as high as R300 per pack of 20 or R3 000 per carton of 200 cigarettes. This is significantly higher than the 90% increase in cigarette prices observed in an earlier survey in May 2020 by the same research team.”

This second study was based on more than 23 000 respondents. “Nearly 30% of respondents indicated that they had tried to quit during the lockdown. The main reason for wanting to quit, as indicated by 56% of respondents who tried to quit, was the high prices of cigarettes. Another 14% of respondents indicated that they had tried to quit because they were unable to find cigarettes. Only 11% of respondents that tried to quit indicated that they did so because of the sales ban.”

The report found large demographic disparities amongst those who reported that they had successfully quit smoking cigarettes. Nearly half of African females and more than a third of African males who answered the survey indicated that they had successfully quit smoking. At the other extreme, fewer than 4% of white male and fewer than 2% of white female respondents indicated that they had successfully quit smoking during the lockdown. More than 70% of smokers who quit did so before May 2 2020, that is during the level 5 lockdown. Van Walbeek says: “The intended lockdown benefit of people quitting smoking was mostly realised in lockdown level 5. The percentage of respondents who quit subsequently has decreased to little more than a trickle.”

The average pre-lockdown consumption of quitters was about half of that of continuing smokers, suggesting that quitters were less addicted than continuing smokers.

“Of the respondents who continued smoking, 93% indicated that they had been able to purchase cigarettes during the lockdown period. Most respondents had purchased cigarettes through informal channels, such as friends and family (27%), spaza shops (25%), street vendors (11%) and WhatsApp groups (8%). Formal retail outlets, which were the predominant source of cigarettes before lockdown (53%), have all but disappeared (0.3%).

According to Van Walbeek: “The tobacco sales ban during the lockdown has thrown the cigarette market into disarray. The market has completely changed. Whereas previously multinationals dominated the market, their share of sales has decreased to less than 20% among the people who were sampled. Most of our respondents have been forced to switch brands, a large proportion of which are produced by local manufacturers.”

In commentary on its report, REEP states: “More than 50% of all cigarettes purchased by respondents in their most recent purchase were brands from three companies affiliated with the Fair-Trade Independent Tobacco Association (FITA). These companies are Gold Leaf Tobacco Corporation (26%), Carnilinx (14%) and Best Tobacco Company (11%). British American Tobacco, which has dominated the industry for decades, had fallen to fifth place, with its brands having been purchased by only 9% of survey respondents who continue to smoke.

“The average daily number of cigarettes smoked by continuing smokers decreased from 16.4 cigarettes pre-lockdown to 13.1 cigarettes in June 2020. Half of these respondents smoked less during lockdown than before lockdown, 15% smoked more, and 35% smoked the same amount,” the report states.

Tobacco producers welcome new research confirming that cigarette ban has failed

The research has spoken!

That was the response from the South Africa Tobacco Transformation Alliance (SATTA) to new research by UCT’s Research Unit on the Economics of Excisable Products (REEP) on the impact of the ban on cigarette sales.

The legal tobacco industry used to provide a livelihood to many in South Africa

The legal tobacco industry used to provide a livelihood to many in South Africa“The research — the only study we are aware of into the impact of the cigarette ban —shows one thing: that the ban has done nothing but stimulate illegal activity, and should be lifted immediately,” says SATTA.

“Alarmingly, the REEP report points out that the longer the ban continues, the harder it will be to get rid of criminal cigarette networks. Government’s arguments for banning cigarette sales have been destroyed by research. Plain and simple.”

At the beginning of the lockdown, government claimed it wanted to stop people sharing cigarettes as it believed this would contribute to the spread of Covid-19.

“But the research reveals that more and more smokers are sharing cigarettes now — in some cases, the figure has gone up 430% in two months,” says SATTA. “So the ban has been a failure.

“Government claimed that banning cigarette sales would stop people from buying cigarettes. But the report reveals that 91% of smokers were found buying illegal cigarettes in May, and the figure now stands at 93%. Another failure.

Tobacco processors have had to put their businesses on hold due to the ban on cigarette sales

Tobacco processors have had to put their businesses on hold due to the ban on cigarette sales“The research also showed that illicit cigarette traders are making massive profits, as the average price of some illicit brands increased by 457% during the lockdown. That is money that is lost to the fiscus. Yet another failure.”

SATTA is a co-respondent to a court application — due to be heard next week — to have the ban lifted, and firmly believes that the UCT research supports its arguments. Its members include tobacco farmers, processors and manufacturers.

“We have long argued that government is losing out on much-needed tax revenue during the ban: in our estimation, R36-million a day. Now there is an additional, compelling reason to lift the ban: the research unit’s finding that all the ban is really doing is entrenching the black market.”

SATTA said government would come to regret its decision to ban the sale of cigarettes, but that this may come too late.

“Right now, tobacco farmers are threatened with the loss of their businesses, tobacco processors have had to put their business on hold, and thousands of jobs are at risk across the value chain.

“Every day that goes by, every new bit of scientific evidence, shows the importance of getting rid of this ban and going back to producing and selling cigarettes as we were before Covid-19.

Hundreds of thousands of people in the tobacco value chain may have to join the unemployment queues

Hundreds of thousands of people in the tobacco value chain may have to join the unemployment queues“But by that time, we fear, hundreds of even thousands of people could have joined the unemployment queues alongside millions of other South Africans who have lost their livelihoods during the Covid-19 lockdown.”

SATTA recently launched a national campaign to have the ban lifted.

“The fight against illicit trade is also one of the two pillars of our current #LiftTheBanSA campaign to have the ban lifted, the other being the need to save the jobs of the 296 000 people involved in the legal tobacco value chain,” says SATTA.

“South Africa is the only country in the world where cigarettes have been banned as a result of Covid-19. This has been devastating for our economy, and has put the entire value chain on hold. The ban must be lifted, and lifted soon, to save the livelihoods of everyone involved in their production.”

Strange trend in smoking’s impact on Covid-19, says Africa Check

The evidence is still inconclusive regarding tobacco, research reveals

At the heart of the argument about the government’s ban on the sale of tobacco products is health, and therefore medical research is under the spotlight, but the government’s argument is far from convincing.

Africa Check, whose function is to fact check claims of all types, asked Petrie Jansen van Vuuren, a medical doctor based in Gauteng with a background in human physiology research, to fact check some of the claims made regarding the impact of Covid-19 on smokers. His report was published on Africa Check’s website on June 12.

In justifying the ban, Minister of Cooperative Governance and Traditional Affairs Nkosazana Dlamini-Zuma cited various statistics which Dr Jansen van Vuuren found could be traced to a small review of available evidence published early in the outbreak. “This analysed five studies from China, with a total sample size of 1 549 Covid-19 positive patients. Fifty-two of them were smokers. The conclusion that the review reaches, and which has been shared by the minister, is that the severity of Covid-19 is greater in smokers.”

Jansen van Vuuren then checked to see whether smokers are really at greater risk from what more recently published research reveals.

A review of 45 studies on smoking shows it increases the duration of symptoms of viral lung infections by up to a day on average. Depending on the illness studied, current smokers are between 34% and 200% more likely to develop influenza-like illnesses than non-smokers.

“In light of this, governments could be tempted to crack down on smokers during a viral public health crisis. Covid-19 has, however, turned established convention on its head. At present there are no randomised controlled studies — the type of studies which are among the most rigorous — which have directly investigated the effect of smoking on Covid-19. This means we have to gather our data via other methods,” says Jansen van Vuuren’s report.

“One way is to compare the characteristics of people infected with Covid-19 with the larger population. One of the largest studies on this comes from a collaboration between the International Severe Acute Respiratory and Emerging Infections Consortium and the World Health Organisation. It is an ongoing project involving 208 acute care hospitals in England, Scotland and Wales. A total of 20 133 Covid-19 positive patients are included in the study. Of those asked, 6% are current smokers, compared to 15% of the British population.

“Another frequently cited report published by the US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention looked at 7 162 Covid-19 patients for whom they had complete data for underlying conditions. Of these, 1.3% were current smokers, compared to 15.6% of the American population. Twenty-two of the smokers were hospitalised and five admitted to intensive care units.”

Due to the short timeline of current Covid-19 research, a number of “pre-print” studies have been released. These are studies that have been submitted to a journal and are currently undergoing peer review — the process where studies are evaluated and validated.

A pre-print study was conducted on 3 789 US veterans, of whom 42.3% were smokers. It found that smokers were underrepresented among the 585 patients who tested positive for Covid-19. Among them 159 (or 27%) of smokers tested positive.

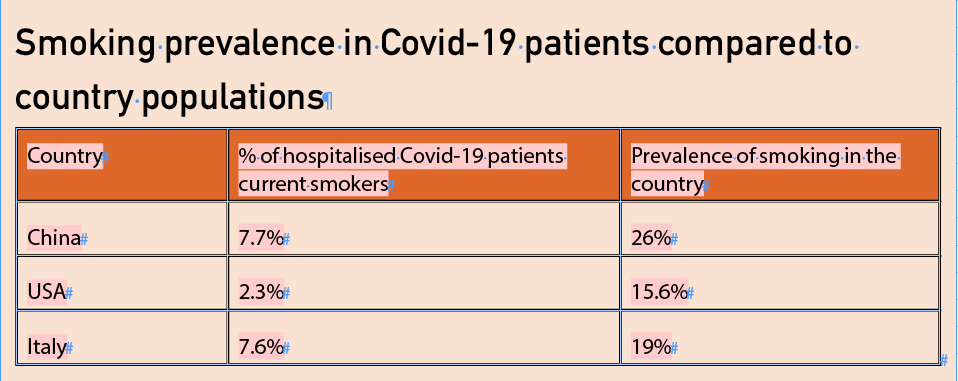

Another meta-analysis, or “study of studies”, looked at 15 Chinese studies, two small studies from the US and one from Italy. The results showed that the number of smokers hospitalised for Covid-19 was lower than expected when compared to the prevalence of smoking in the countries.

“This data yields a bizarre trend — smokers do seem to be less likely to end up hospitalised with Covid-19.”

What happens to smokers in hospitals?

“A 2020 meta-analysis from the University of California in the US looked at 19 peer-reviewed papers with data from a total of 11 590 Covid-19 patients. In 29.8% of patients with a history of smoking, the disease became more severe or resulted in death. In comparison, this happened to 17.6% of non-smoking patients.

“Taking a step back and looking at all of the data presented here we can tentatively agree with the hypothesis that smokers are less likely to be admitted to hospital with Covid-19, but once they are in hospital, their outcomes are similar at best and likely worse than non-smokers,” says the report by Jansen van Vuuren.