Manchester City's Pep Guardiola and Liverpool's Jurgen Klopp during the Premier League match between Manchester City and Liverpool at Etihad Stadium on September 9, 2017 in Manchester, England. (Photo by Tom Flathers/Manchester City FC via Getty Images)

It’s hard to shake the weirdness. The Premier League’s initial post-pandemic return in June was hailed as defiant in some corners, reviled for its pandering to television overlords in others. This time around, just a month delayed from when the 2020-21 season would have started under normal circumstances, there’s barely a murmur from either side.

We’ve come to accept that the Premier League is an inseparable part of our lives. It’s that soapie we routinely flick to out of habit as much as anything else.

And yet, you would struggle to find a fan not willing to drop to their knees in gratitude to the heavens for allowing play to resume. All those op-eds that pontificated about how sport has discovered its true irrelevance and learned its place in our new reality were ignorant to just how voluminous the appetite for the game is.

In the eyes of Premier League organisers, this is enough justification for continuing as if everything were normal.

Nothing is normal

Earlier this week, two Manchester City players tested positive for Covid-19. Meanwhile, two English boys were also put on the naughty chair for Covid-19 irresponsibility. Mason Greenwood and Phil Foden were sent home during international duty in Iceland after they invited local women into their hotel room, popping the pseudo bubble they were supposed to be floating in.

This may be an isolated incident, and the league has strict protocols in place. Still, it would be straight-up silly to presume its collection of obscenely paid, famous teenagers are capable of abiding by them for nine months without incident.

Riyad Mahrez and Aymeric Laporte, meanwhile, had their tests return positive and it is now doubtful they will be able to put in enough training to make City’s pushed-back opener against Wolves in a week’s time. Chelsea, similarly, had as many as eight players pushed into self-isolation because of a recent scare, disrupting preparations. These situations have fortunately fallen in the preseason and have been contained — no one seems to know what will happen if a significant number of players in any given team are forced out of action going forward.

The practice of predictions is fraught at best; now, it’s nigh impossible. The enhanced unpredictability is set not just to be a feature of the new season, but rather its defining storyline.

Fortunately, from a pure footballing perspective, that will only add further flavour to already rich subplots.

Can Liverpool be figured out?

In the football media, we love to talk of teams getting “figured out”. It happens to everyone, no matter how good you are. Fall victim to this fate and you land up in our sports pages as the stubborn duck who failed to adapt.

Liverpool is not there, yet. Bar a few wobbles, most of which came when the title had been long secured; this team was practically unplayable last season.

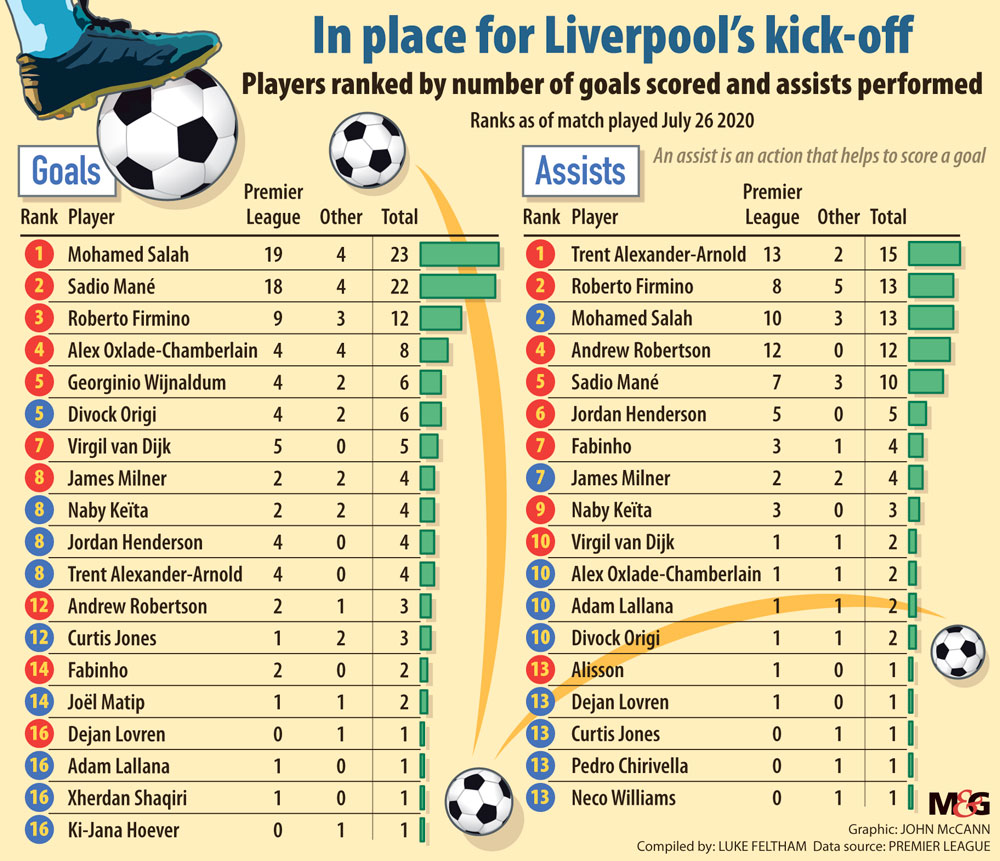

Jürgen Klopp plays a direct, fluid style that aims to stretch the field as much as possible, while the manager’s strategic novelty comes from his aggressive use of his fullbacks. Modern defenders have long been expected to surge forward, but in Trent Alexander-Arnold and Andrew Robertson he has two who don’t just support the attack, but are a fundamental part of it.

Klopp likes to build from the flanks, crisscrossing from side to side with long balls that often bypass the midfield entirely. The fullbacks work in tandem with the famed front trident of Mohamed Salah, Sadio Mané and Roberto Firmino to create one-two opportunities and space for scything overlapping runs.

The central midfielders, by contrast, are the robust disrupters of the piece, asked to do plenty of running and hacking, but not to shoulder the creative burden. To illustrate this, 72% of the outfit’s Premier League assists last season belong to the five attacking players we’ve mentioned.

Which brings us to our original question: How do we stop it? Going back to last year’s footage, every team that beat Liverpool, or came close to doing so, was able to force an advantage through the space left behind by the fullbacks.

The front three work so magically well together because Klopp has a laissez-faire attitude to their defensive duties and allows them to flit up front without tracking back. This leaves Alexander-Arnold and Robertson vulnerable to being hit when they’re on the back foot.

Generally the midfielders, Georginio Wijnaldum being the prime example, do an exceptional job of covering for them, which is why this obvious “weakness” has not been more thoroughly exposed. Make no mistake, however: there are 19 Premier League managers working tirelessly on a formula to force open those cracks more effectively.

Blue money speaks

Manchester City is first in line to benefit from any Liverpool slip-ups. They remain one the greatest sides of this generation and only looked poor next to their own ridiculously good precedent. Plus it’s practically a law of physics that Pep Guardiola does not stay down for a prolonged period. No one will be shocked if he’s hoisting silverware come May.

A far more intriguing storyline to follow is whether Chelsea can also force their way into the title conversation after an epic spending spree.

Although the market has mostly reeled under the pandemic, the Blues have tucked into their Eden Hazard-funded savings and have spent more £200-million to procure some of the hottest talents in Europe (the returning interest of oligarch owner Roman Abramovich also helps).

The Blues were a beautiful mess in Frank Lampard’s debut season in top-flight management. Under the circumstances — a transfer ban and the loss of Hazard — a fourth-place finish was an admirable achievement but the end result didn’t mask the shambles we saw at Stamford Bridge on occasions. It was particularly bad in defence: Chelsea shipped more goals (54) than any other team in the top 10.

The real excitement remains up front. In that area, it was only City and Liverpool who scored more goals over the same period. Christian Pulisic, fully recovered from his injury woes, also put his name down as one of the stand-out players in the league after the restart. With the creative talents of Hakim Ziyech and Kai Havertz arriving to supplement his enterprise, and Timo Werner adding a deadly poacher’s touch, it’s scary to think of the attacking potential of this team.

That’s all theoretical for now, but if the parts fall together, we could see something exceptional. Of course, with promise comes expectation. Lampard has acknowledged his honeymoon in the dug-out is now over. He will know better than anyone what happens to managers that fail to impress the Roman emperor.