People’s pollution: Bob the Green Turtle is living up to his name – he’s bobbing along in Cape Town’s aquarium and soon to be released into the sea. (Jean Tresfon/2OceansAquarium)

Bob the Green Turtle loves peppers and back scratches. He enjoys a cuddle too, says Talitha Noble, one of his main carers at the Two Oceans Aquarium in Cape Town.

“He is such an incredible turtle — he is just a little bit of extra work,” says Noble, the conservation coordinator and the head of the turtle rehabilitation programme.

The endangered turtle, who was named Bob because he liked to bob in his tank, was brought to the aquarium in November 2014 after he was discovered stranded on rocks at the De Hoop Nature Reserve.

Wounds on the underside of his shell — his plastron — became infected and caused meningitis. Bob became blind and suffered brain damage.

“Slowly over time we were able to help him and give him medication and he started to heal. His eyesight began to recover and he started to behave normally, but we were uncertain what that [the brain damage] would mean for his releasability.”

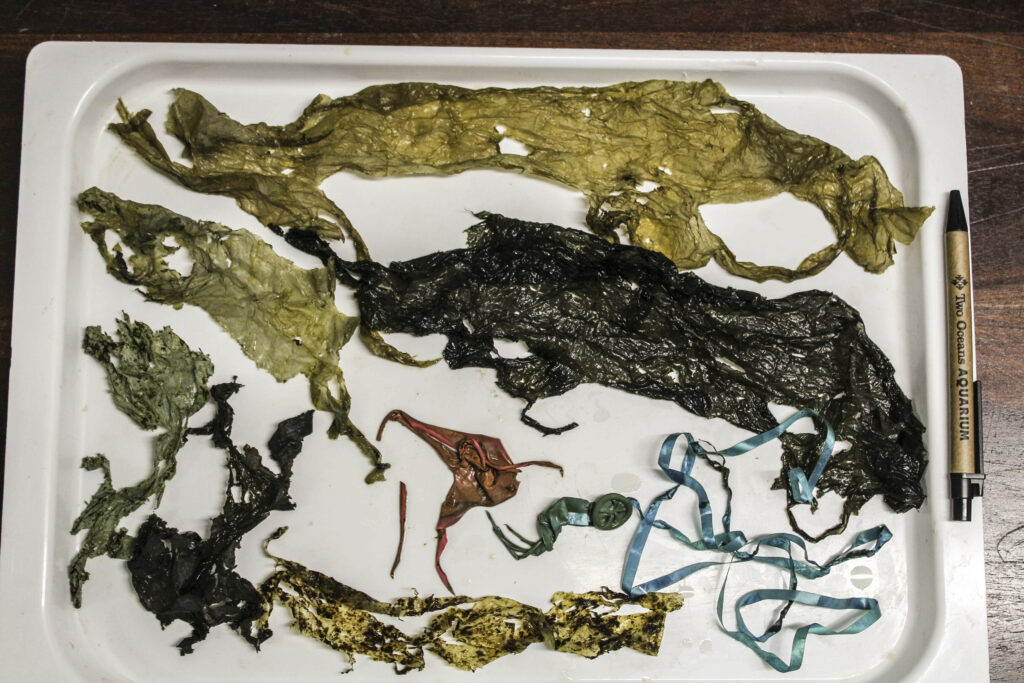

Three months after Bob’s arrival, he pooped out a pile of plastic: pieces of balloons with their strings still attached, ribbon and black bags that he had mistaken for food in the ocean.

Bob the turtle became ill after ingesting plastic bags, a balloon and a ribbon he had mistaken for food

Bob the turtle became ill after ingesting plastic bags, a balloon and a ribbon he had mistaken for food

Consuming the plastic detritus probably hindered his ability to digest food, says Noble.

“This would have very easily made him feel weaker, which would have made him sicker, which would have ultimately led to him being tumbled around on the rocks and having these injuries, which are then what caused the infection and the brain damage.

“It’s unfortunately an issue we see with a lot of our turtles who have ingested plastic. Even the ones who survive, it’s probably a very big contributor to them being so sick.”

The goal has always been to return Bob to his natural ocean home. But his brain damage means that his recovery is ongoing and getting him well enough to be released is complicated and expensive.

“He has damage to his mid-brain so he is slightly slow to interpret what he sees. It still makes him releasable — it just means we have to put a lot of effort into his rehabilitation.

“It’s a bit like you would treat a child with special needs,” says Noble.

“He probably needs some occupational therapy and extra exercise.”

She says that for them to know whether Bob is ready to be released they would need to place him in an environment very different to where he is now to see how he can cope.

In this environment, he would have to prove that he can dive well, look out after himself, find food — all the things he would need to do to survive in the ocean.

On Thursday, Noble immersed herself in the icy Atlantic Ocean, braving a 7.5km swim from Robben Island to the mainland to raise awareness and funds for sea turtle rescue, particularly for Bob.

She swam so that one day Bob can too can swim free. The funds raised will be used for specialist consultations and medical tests, enrichment equipment, mental therapy work — and Bob’s R1 500 monthly food bill.

Extreme swimmer Ryan Stramrood, who holds the record for the most Robben Island crossings ever swum (112), has provided guidance and support.

Noble says Bob has become an ocean ambassador, teaching people how dangerous plastic is.

“Turtles are so special. They talk about issues that are really horrific and quite depressing, but they are also very much agents of hope and strength.

“They are storytellers who leave people feeling inspired to want to be better and want to change. Bob’s done that for me and he does that for so many hundreds of thousands of people who come through the aquarium every year.”

Many turtles, especially hatchlings, arrive at the rehabilitation facility, their bellies full of plastic.

“Recently we had a hatchling that pooped out nurdles [lentil-sized plastic pellets]. Plastic pollution is a massive issue turtles face,” says Noble.

“What’s exciting is that every turtle who comes in that has plastic in it, there’s been a whole army of people who have been part of the journey who are now passionate turtle rescuers, committed to wanting to rescue turtles through the way they live.”

She added that turtles bridge the gap between oceans and humans.

“We realise this plastic bag … it’s going to end up in the ocean. Or that this plastic bottle or single-use coffee cup I buy will probably end up in a landfill and then into the ocean if I don’t stop using it.

“Turtles act as such clear communicators. That leaves me inspired every day.”