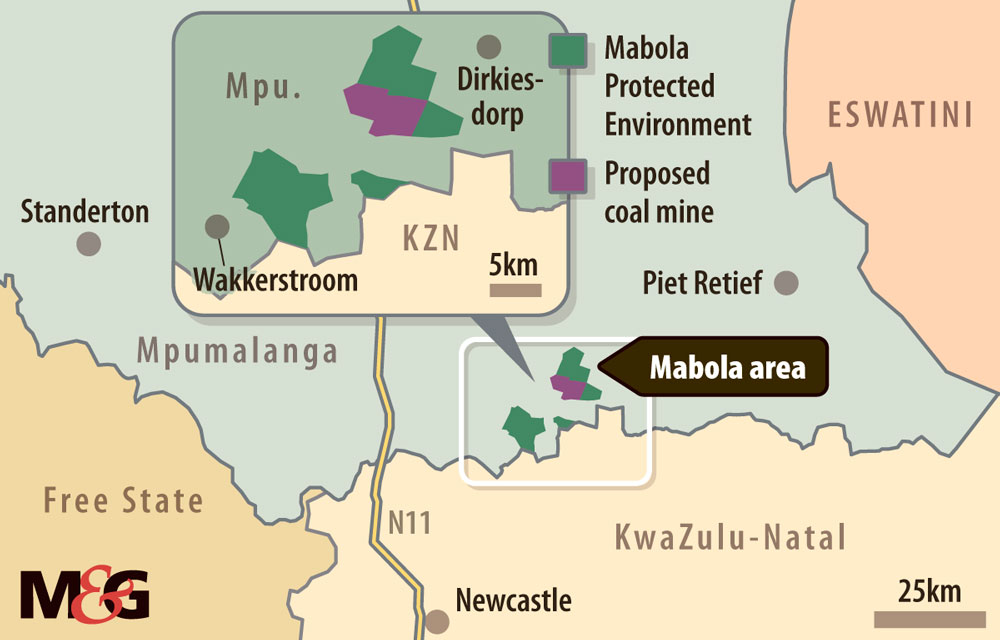

Undermining: The Mabola Protected Environment in Mpumalanga, which supplies South Africa with half of its water, is once again being threatened by coal mining.

(Robert C Nunnington)

The protected status of a large part of the Mabola Protected Environment area near Wakkerstroom has been revoked by Mpumalanga’s minister for agriculture and environmental affairs. Now the way appears to have been cleared for a firm linked to Jacob Zuma’s relatives to mine for coal there.

On 8 December, MEC Vusi Shongwe published a notice of exclusion “to promote the co-existence of mining activities and conservation” in the biodiversity-rich protected area, a strategic water source area.

The planned underground coal mine, Yzermyn, is a project of Uthaka Energy, formerly Atha-Africa Ventures. Its black economic empowerment partner is the Bashubile Trust, whose trustees include Vincent Gezinhliziyo Zuma and Sizwe Christopher Zuma, reportedly nephews of the former president.

Mabola, which was established in 2014 under the Protected Areas Act, is home to high-altitude grasslands, highly sensitive wetlands and pans that support endemic plants, bird and animal species as well as unique and endangered ecosystems.

Mabola falls within the Enkangala-Drakensberg Strategic Water Source Area, one of 22 such water factories that produces half the country’s fresh water, despite comprising just 10% of land area.

A coalition of eight nonprofit public interest organisations, who have challenged Yzermyn’s authorisation since 2015, say the exclusion undermines South Africa’s existing protected area network.

“The decision sets a dangerous precedent for the withdrawal of protection for protected areas, including national parks, to allow mineral deposits to be mined inside these iconic places of natural heritage that belong to all South Africans.”

The coalition comprises the Mining and Environmental Justice Communities Network of South Africa, groundWork, Earthlife Africa Johannesburg, BirdLife South Africa, the Endangered Wildlife Trust, the Federation for a Sustainable Environment, the Association for Water and Rural Development and the Bench Marks Foundation. It is represented by the Centre for Environmental Rights.

The coalition says Shongwe’s decision disregards the reason Mabola was declared a protected area, such as “its biological diversity and the provision of environmental goods and services, protection of a specific ecosystem, and protection to ensure that the use of natural resources in the area is sustainable”.

Persistent: Environment and agriculture MEC Vusi Shongwe wants protection of Mabola revoked

Persistent: Environment and agriculture MEC Vusi Shongwe wants protection of Mabola revoked

Shongwe said the exclusion would “ensure balance towards the use of natural resources for socioeconomic benefits” of the residents of Pixley ka Seme local municipality and the country” while “promoting environmental protection and sustainability”.

The coalition says his decision “flies in the face” of the municipality’s own 2020 Spatial Development Framework, which views the Wakkerstroom landscape as a “priority conservation site” where “steps must be undertaken by authorities to ensure that the natural environment is protected … no development will be allowed in areas that include any form of water bodies”.

Under the Protected Areas Act, mining is forbidden unless permission has been granted by the ministers of environmental affairs and mineral resources.

The coalition describes the MEC’s decision as an attempt to circumvent the joint ministerial permission required to allow mining in Mabola and “appears to be an attempt to avoid an earlier court judgment setting aside an approval previously given unlawfully”.

In November 2018, the high court in Pretoria set aside the 2016 decisions of the then minister of mineral resources, Mosebenzi Zwane, and then minister of environmental affairs, Edna Molewa, to permit the new coal mine to be developed in Mabola. Four attempts by Atha-Africa to challenge this were unsuccessful, culminating in the Constitutional Court, leaving the high court decision intact in 2019.

The minister for the environment, forestry and fisheries, Barbara Creecy, in October 2019 advised Shongwe against withdrawing the mining area from Mabola, highlighting the implications of such an action in relation to the high court judgment, said the department’s spokesperson Albi Modise.

“The MEC was also advised to ensure that the management plan of the Mabola Protected Environment is finalised; and that such a finalised management plan, clearly indicate zones where multiple land uses may be considered within the Mabola Protected Environment, including areas where sustainable resource extraction may be allowed. This was to ensure that a process of decision making in terms of section 48(1)(b) of NEMPAA [National Environmental Management: Protected Areas Act], read with the conditions for decision-making that are prescribed in the judgment, is facilitated, should Atha-Africa Venture resubmit the application for consideration.”

On 17 December 2020, the minister received a letter from the MEC, telling her of his decision to withdraw the area from Mabola.

Several high court applications to set aside the authorisations needed to start mining are pending.

GroundWork’s Bobby Peek said the mine would not create meaningful local employment to justify the local and downstream consequences of “compromising this strategic water source area and the long-term water pollution, the health impacts of air pollution, the greenhouse gas emissions causing climate change, and the loss of natural resources like grasslands, wetlands and water supply”.These are essential for South Africa’s ability to protect itself from the worst impacts of climate change.

Praveer Tripathi, of Uthaka Energy, said the coalition’s statement was “misleading” and referred the Mail & Guardian to the Voice Community Representative Council, which is backing its venture.

Its chair, Thabiso Nene, lauded the MEC’s decision. It had handed Shongwe a petition supported by over 8 500 signatures to withdraw the protected status, along with a detailed scientific study demonstrating that “these areas, being historically transformed with mining activities, did not deserve to be protected. We … are glad that the panel and the MEC understood the urgent need to address the development and unemployment problems of the community.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)