Determined: Climate change demonstrators from the environmental activist group Extinction Rebellion protest in central London, promising two weeks of disruption. (Tolga Akmen/AFP)

The company that the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) fined $19-million for claims of improper payments to the ANC’s funding arm, Chancellor House, is a major partner of the United Nations Climate Change conference (COP26).

Hitachi’s local subsidiary, Hitachi Power Africa, chose Chancellor House as its black economic empowerment partner in 2005, to bid for contracts at Eskom’s Medupi and Kusile power stations.

According to its website, “Hitachi Power Africa executes power plant orders comprising the manufacturing, supply, construction and commissioning of fossil fuel-fired power plants as well as steam and gas turbines in the Southern African region.”

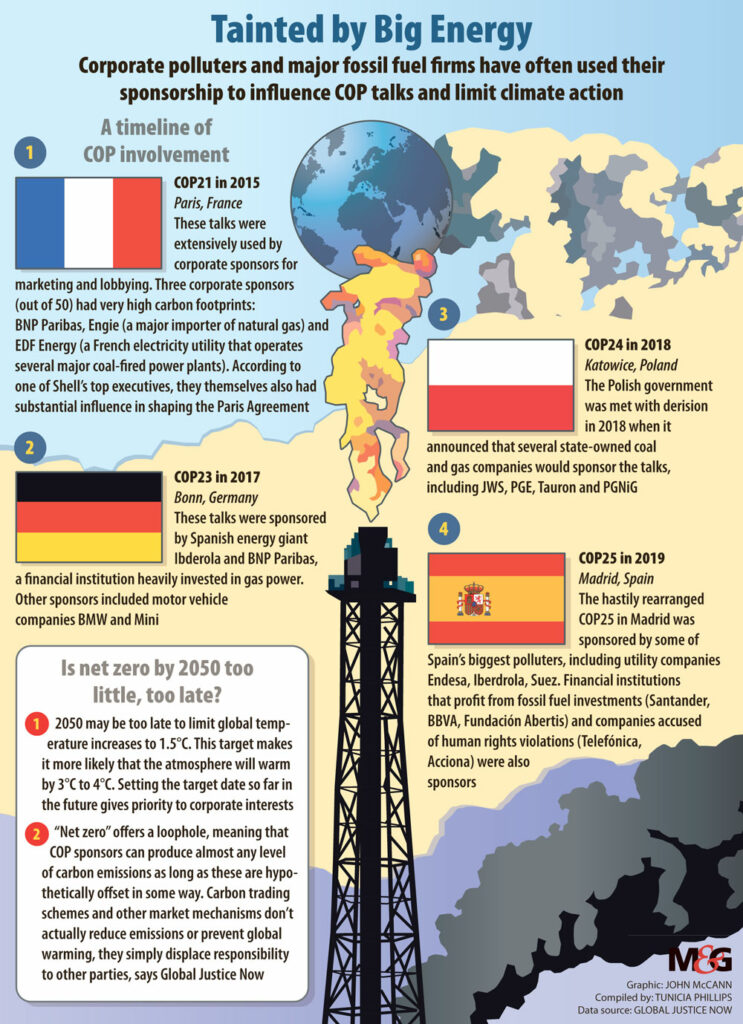

The COP26 will be held in Glasgow, Scotland, from 31 October to 12 November and will bring countries together to accelerate efforts to meet the 2015 Paris Agreement to limit global warming, adaptation and finance. The 2021 meeting looks set to follow a similar pattern to previous ones, where host countries have partnered with sometimes tainted fossil fuel companies as sponsors.

In 2005, Valli Moosa, who is now deputy chair of South Africa’s presidential climate commission, was chair of Eskom while serving on the ANC’s finance committee.

The SEC file alleged that Hitachi was aware that Chancellor House was an ANC funding vehicle during the bidding process, but nevertheless encouraged the company “to use its political influence to help obtain government contracts” from Eskom. It said Hitachi paid “success fees” to Chancellor House for its work.

The coal-fired power plants in question, Medupi and Kusile, have been marred by drastic cost overruns, explosions, corruption and design defects.

A stage for greenwashing

Views on the role of fossil fuel companies in public and private sectors at the UN’s climate talks are divided.

South Africa’s pavilion at the 2019 conference in Madrid, Spain, was sponsored by the country’s biggest greenhouse gas emitters, Eskom and Sasol.

The COP25 conference was bankrolled by Spain’s top energy giants, Endesa and Iberdrola, which account for the bulk of that country’s greenhouse gas emissions. Iberdrola also sponsored the 2017 COP in Bonn, Germany, as well as the landmark conference that led to the 2015 Paris Agreement.

Activists are increasingly ringing alarm bells over how such sponsorship “compromises the talks” and leaves room for bankrolled trade organisations to lobby to water down decisions on climate action.

In 2018, Corporate Accountability International released a report condemning how coal and oil groups undermined UN climate negotiations.

“With so many arsonists in the fire department, it’s no wonder we’ve failed to put the fire out,” said Tamar Lawrence-Samuel, an author of the report.

Culture Unsustained, an organisation campaigning against fossil fuel sponsorship, said it had obtained, through a Freedom of Information request, correspondence between the United Kingdom’s COP26 unit and oil and gas companies such as BP, Equinor and Shell regarding high-level sponsorship for the conference.

The unit determined that the firms did not meet the required criteria because of their weak climate plans.

“As well as setting out robust ‘climate criteria’ for corporate partners, the government decided that firms with ‘serious violations of human rights and environmental law’ would be automatically excluded from the application process,” the organisation said.

“This means that as well as being rejected because of their insufficient ‘net zero’ commitments, firms such as BP and Shell might also have been excluded due to their significant environmental impacts.”

It said the climate conferences had offered major polluters an international stage where they could attempt to “greenwash” their brands “through swanky side-events, prominent PR campaigns and high-profile sponsorship deals”.

Despite a big block on oil sponsorship, power companies responsible for historical emissions are an exception.

Hitachi, National Grid, a British multinational electricity and gas utility company, Scottish Power energy company and SSE, also a multinational energy company in Scotland — not mentioned in the Centre for Research on Multinational Corporations (Somo) report — are the current sponsors of the UK-led COP26.

The Guardian has reported that these power companies have penned a letter to the UK government complaining about a lack of branding exclusivity and unsatisfactory coordination.

A COP26 spokesperson told the publication that “COP isn’t about branding, it’s about tackling climate change. Keeping 1.5°C in reach is the best thing you can do for your bottom line: they would do well to remember this.”

Hitachi Global, the COP26 principal partner, is helping the UK’s Royal Mail to go green through electrifying its fleet and the rail sector.

Companies such as French oil giant TotalEnergies agree with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change’s view that the climate talks must include fossil fuel companies.

In a statement, TotalEnergies said that all of society must participate in the road to net zero carbon emissions by 2050. “Energy transition is a global debate and there is consequently a necessity for society as a whole to participate,” said chairperson and chief executive Patrick Pouyanné.

Early warnings ignored

TotalEnergies is the subject of a report that said the company knew about the effect of their activities on climate change for 50 years, and did nothing.

Environmental rights organisations 350.org and Notre Affaire à Tous last week launched a campaign against TotalEnergies.

It coincided with an article published in the international journal Global Environmental Change, in which three historians reveal that the managers and employees of TotalEnergies (at the time Total and Elf) were warned as early as 1971 of the possibility of unprecedented climate change caused by the production of fossil fuels.

The authors said Total fought any regulation to control or limit its activities and used numerous strategies to undermine climate science.

Justine Ripoll, campaign manager for Notre Affaire à Tous, said legal frameworks and lawsuits were proving to be more and more effective in getting multinationals to respect their climate commitments, as demonstrated by the case of Royal Dutch Shell in the Netherlands, where a court forced the company to set targets for alignment to the commitments in the Paris climate accord.

TotalEnergies dismissed the allegation: “Total Energies deplores the process of pointing up at a situation from 50 years ago, without highlighting the efforts, changes, progress and investments made since then.”

Six NGOs have sued Total for its controversial oil project in Uganda and Tanzania. The plaintiffs allege that the company failed to adequately assess the project’s threats to human rights and the natural environment.

Fossil fuel energy companies blandishing climate change diplomacy with branding and announcements on net zero 2050, are not only responsible for environmental rights violations and graft but have been fingered in human rights violations with severe social consequences in coal-driven communities.

A report by Somo found that a number of European energy companies were responsible for human rights violations in Colombia. In the violence-hit Cesar region, mining companies such as Glencore continued to expand despite paramilitaries displacing people and occupying coal mines.

“Several European energy companies have made significant and repeated purchases of coal from Cesar mines to generate electricity in their power plants. Somo contends that the relationship between these companies and the forced displacements has shifted from being initially directly linked through their relationship with Drummond and Prodeco/Glencore to contributing,” the organisation said.

In 2017, Oxfam launched a report on Sasol’s gas developments in Mozambique. At the time the Mail & Guardian reported that residents of Maimelane in Mozambique’s Inhassoro district in Inhambane province bemoaned slow development in their area near the gas wells. Mining activists delivered a report highlighting that Sasol had failed to achieve the projected annual government revenue share because of the low pricing of the gas.

It recommended a review of the Mozambican government’s contract with the South African-based multinational. Sasol said the report downplayed its contribution to Mozambique.

Tunicia Phillips is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow funded by the Open Society Foundation