Denuded: The Amazonia rainforest in Brazil. The Amazon Basin absorbs large amounts of CO2 emissions. Photo: Mauro Pimentel/AFP/Getty Images

The year 2021 was dominated by headlines about the devastating fires around the world and those that ravaged the Amazon rainforest, the planet’s single largest absorber of carbon dioxide. The situation escalated to the point where scientists said the Amazon was becoming a carbon emitter.

But there is a glimmer of hope. A new study shows that forest regeneration efforts worldwide have yielded promising results for restoring these carbon sinks, which absorb more carbon from the atmosphere than they release.

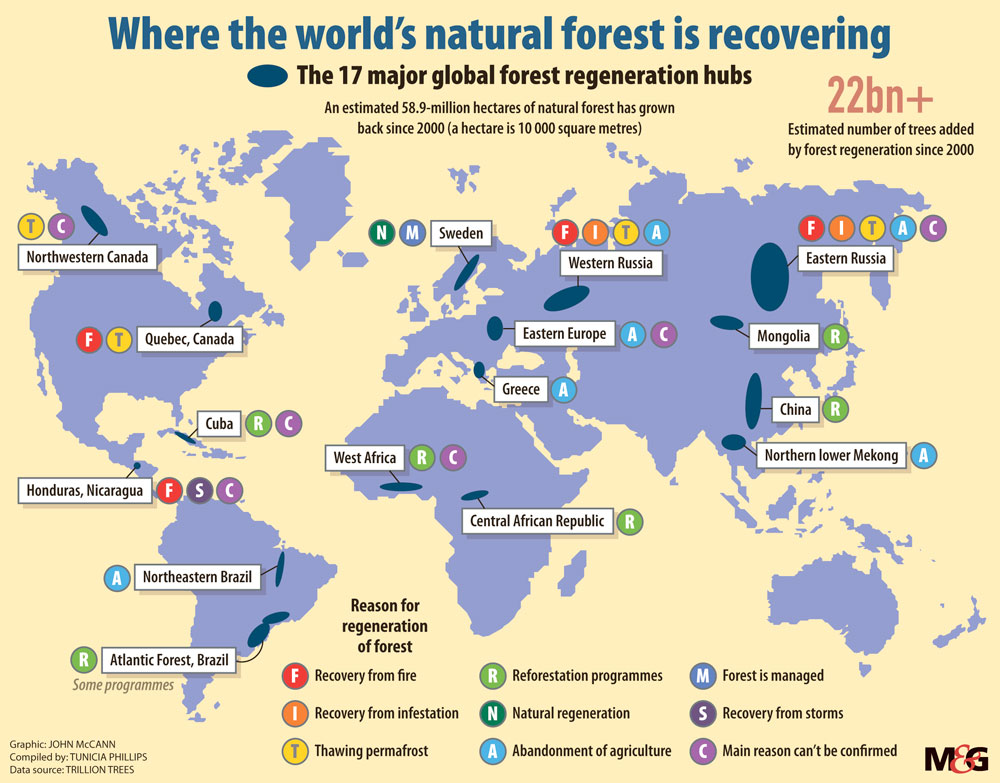

Project Trillion Trees, supported by the World Wildlife Fund, Birdlife International and the Wildlife Conservation Society, began a global survey to assess restoration and regeneration efforts since 2000. It found that these amounted to accumulated tree cover the size of France in the past 20 years. The project resulted in a map that shows an estimated 58.9 million hectares of forests that have regenerated.

“A quick look at the map shows that, while deforestation fronts are concentrated in the tropics, most regeneration has taken place in the northern hemisphere,” according to the survey.

“This is broadly consistent with the forest transition theory: developing economies tend to be more dependent on domestic agriculture and primary industries, and thus have higher rates of deforestation. As countries grow richer, they move towards manufacturing and service industries, freeing up land for regeneration. Natural regeneration can occur in the same locations as deforestation because some of that land cleared for timber or agriculture is abandoned shortly afterwards.

“Regeneration is likeliest to occur in areas that naturally support trees and, although clear-felling can harm the quality and stability of soil, deforested areas are natural candidates for regeneration,” the report read.

Although only 15% of the Mata Atlântica (Atlantic Forest), which stretches from Northern Brazil to Argentina, remains today, researchers said the forest was one of the global success stories for regeneration.

Despite rising deforestation rates in the forest and missed restoration targets, an estimated 4.2 million hectares have regenerated in Brazil since 2000, “much of it focused around the Atlantic Forest biome”.

But the study warned that “this tremendous regeneration cannot be taken for granted”.

“Forests across Brazil face significant threats today, even the Atlantic Forests — a recognised success story in restoration,” the authors wrote.

“Such is the extent of historic deforestation that the remaining area of this unique forest still needs to more than double to reach what scientists believe is a minimal threshold for its lasting conservation,” they added

In another paper published in Nature, Simon Lewis called on conservationists and policymakers to “prioritise the regeneration of natural forests over other types of tree planting [plantations], by allowing disturbed lands to recover to their previous high carbon state”.

At COP26 in Glasgow, Scotland, in November, more than 100 countries signed the Glasgow Declaration on Forests which British Prime Minister Boris Johnson described as a “landmark agreement to protect and restore the Earth’s forests’’. He also called the pledges under the agreement “unprecedented”.

Colombia’s President Iván Duque also said the declaration was a landmark commitment: “Never before have so many leaders, from all regions, representing all types of forests, joined forces in this way.”

The Global Forest Coalition said that under the Glasgow Forest Declaration, 12 countries promised to provide $12-billion until 2025 to restore degraded land and to tackle forest fires. A significant amount of this will probably go to the World Bank’s Forest Carbon Partnership Facility.

But the positive developments are not without criticism. Greenpeace has criticised the Glasgow Forest Declaration as “a green light for another decade of forest destruction”.

And Carolina Pasquali of Greenpeace Brazil, said: “There’s a very good reason [Brazil’s President Jair] Bolsonaro felt comfortable signing on to this new deal. “It allows another decade of forest destruction and isn’t binding. Meanwhile the Amazon is already on the brink and can’t survive years of more deforestation,” her statement read.

Tunicia Phillips is an Adamela Trust climate and economic justice reporting fellow, funded by the Open Society Foundation for SA