New research shows that Hadedas are able to detect vibrations in the soil by their prey, such as earthworms. (Photo by: Arterra/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Hadedas, dubbed “African alarm clocks”, possess a sixth sense that is key to their range expansion in Southern Africa, new research on their extraordinary sensory capabilities has revealed.

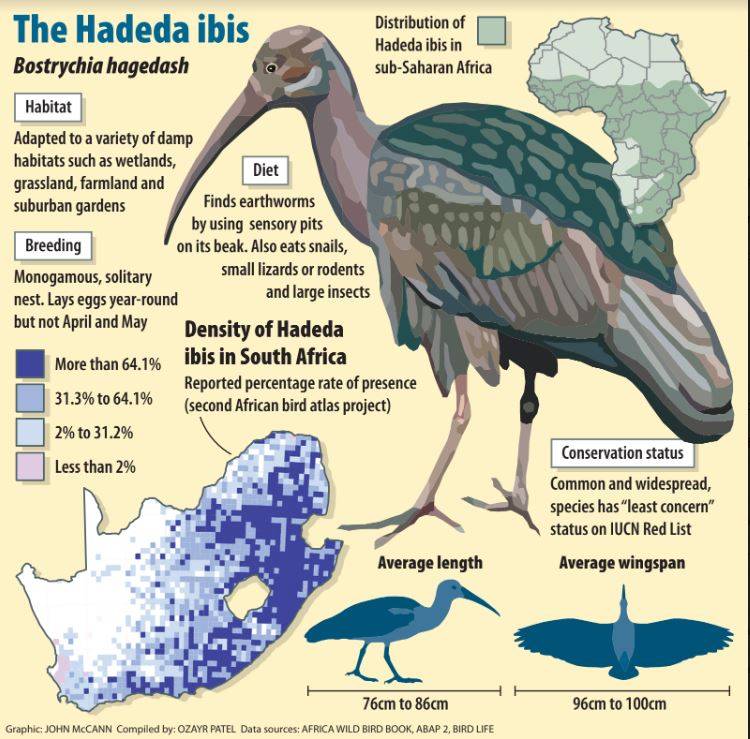

The study by researchers from the University of Cape Town (UCT) found that Hadeda ibises have a unique sensory adaptation that allows them to detect vibrations emitted by buried invertebrate prey, such as earthworms.

Published in the Journal of Avian Biology, it highlights the role of irrigation and the ibises’ remote-tactile foraging abilities in driving their habitat expansion in the region.

The authors noted that this ability is contingent upon the moisture content of the soil. When soil is watered in suburban and agricultural areas, it creates wetter substrates, and the ibises “capitalise on this environmental change to efficiently locate their prey, thereby facilitating their range expansion”.

“The findings of our study underscore the crucial interplay between environmental factors and sensory ecology in shaping the distribution and behaviour of wetland birds,” said Carla du Toit, a researcher from UCT’s biological sciences department and the FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology.

Du Toit, whose doctoral thesis formed part of the study, said Hadedas serve as a compelling example of how species adapt to human-caused modifications of their habitats.

Remote-touch, the ibises’ sixth sense, enables them to detect vibrations from prey items in the substrate, similar to “a fusion of touch, hearing, and echolocation”.

The research, conducted at the World of Birds sanctuary in Hout Bay, shows that the ibises are more successful in foraging success in wetter soils, where vibrations spread more effectively.

“Our results … indicate that Hadeda ibises are able to use remote-touch in the absence of all other sensory cues (visual, auditory and chemical) to locate soft-bodied moving invertebrate prey buried under the ground,” the study noted.

Du Toit said the rapid adaptation of hadedas to changes in soil moisture levels underscores their resilience and adaptability.

She added that the study has improved the understanding of the sensory requirements of wetland birds, which is important for effective conservation strategies, especially when habitats are changing.

Soil irrigation “has not only facilitated the birds’ foraging activities but has also led to their proliferation in suburban and agricultural landscapes”, the authors said.

Their characteristic loud calls have become a familiar feature in urban areas, marking a shift from their historical distribution in eastern regions of South Africa.

“Human activities have inadvertently paved the way for the expansion of Hadeda Ibises into new territories. As we continue to modify landscapes, it’s crucial to consider the ecological implications and potential cascading effects on wildlife,” Du Toit added.

Further studies will look at the tactile sensory systems of modern birds on a global scale, to understand the function and evolution of these senses and the associated organs.