A chain-forming diatom, a common type of phytoplankton, found in the New York Bight area. (NOAA)

Climate models are underestimating the global decline in the productivity of the oceans resulting from ocean warming, researchers from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) have warned.

This finding follows their analysis of 26 years of remote sensing data and comparing these contemporary trends to future projections from a wide range of models.

Their study, which was published in Nature’s scientific journal Communications Earth & Environment earlier this month, was led by the CSIR’s principal researcher Tommy Ryan-Keogh, its chief researcher Sandy Thomalla and ocean biogeochemist Alessandro Tagliabue from the University of Liverpool in the UK.

Ocean productivity is driven by phytoplankton — microscopic marine algae that live in the sunlit surface water of the ocean. This not only forms the base of the marine food chain, supporting higher trophic levels like fish, but also helps to regulate global climate by taking carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere, Ryan-Keogh said.

“If ocean productivity continues to decline then not only is there less food for the marine food chain, which could impact food security for several billion people, but there would be less CO2 taken up from the atmosphere, which could in turn make climate change worse,” he said.

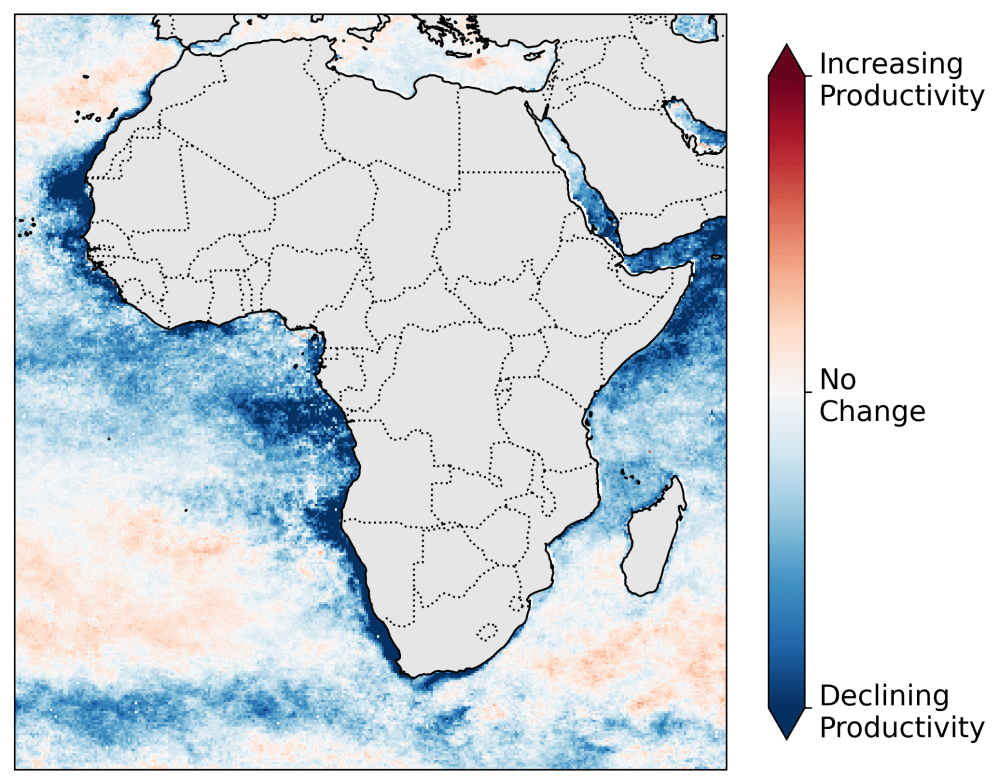

Africa productivity trends (Graphic supplied)

Africa productivity trends (Graphic supplied)

Despite the importance of phytoplankton, scientists do not have a clear understanding of how climate change can affect this diverse collection of invisible organisms that drift in water but are unable to actively swim against currents.

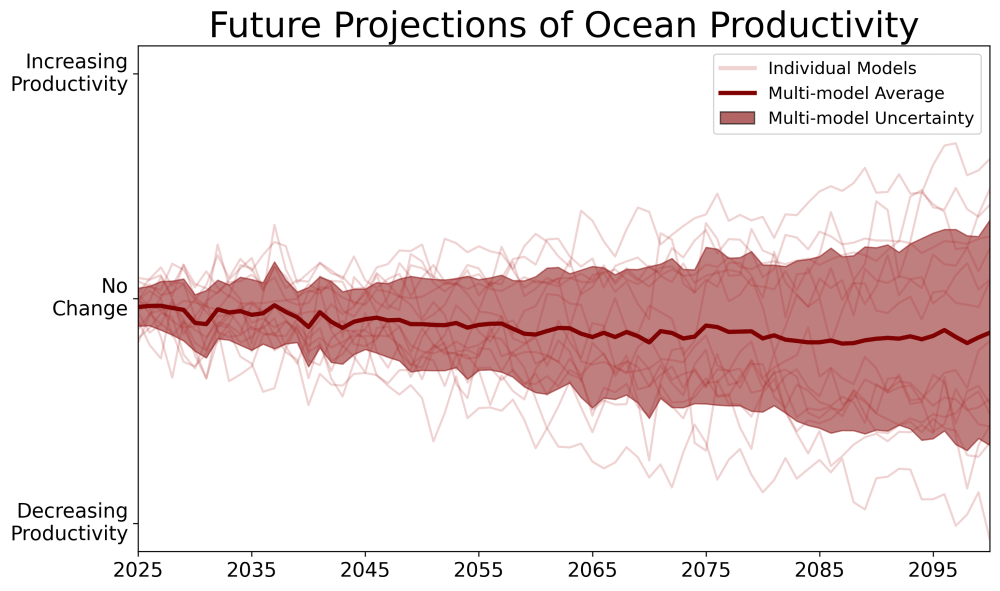

Climate projections from models, used to inform policymakers so that climate targets can be agreed upon, are powerful and important tools, Ryan-Keogh said, adding: “However, the climate projections for ocean productivity were unable to provide a clear picture. Some models suggest that ocean productivity will increase by the end of the century, whereas others suggest it will decline.”

The researchers used a novel approach combining ocean productivity estimates from 26 years of satellite data spanning 1998 to 2023 and projected end-of-century trends from available earth system models to assess climate impact on marine ecosystems.

According to Ryan-Keogh, theirs is one of the first studies to use data from the past 26 years to assess how ocean productivity might be changing and to link these changes to the future state of the oceans.

To predict the changes, the authors developed a model ranking scheme that assessed how well each model can represent the relationships between productivity and different environmental drivers.

Climate models have been underestimating this decline because of how they programme the relationship between temperature and ocean productivity, Ryan-Keogh said. “When we compared the relationship between temperature and ocean productivity from satellites, we found that several models were not getting this relationship correct.

“This allowed us to build a model ranking scheme to determine which models are the most accurate, i.e. which models have programmed these relationships most similarly to what we are observing in the real world. The models which were ranked highest all suggest that ocean productivity will decline by the end of the century.”

However, even those models which the authors considered to be the best are still not getting this relationship completely accurate, “which is why the declines they predict are still much too small when compared to the declines we observe from satellites”.

The team used the supercomputer at the Centre for High Performance Computing to conduct the satellite analyses. Ryan-Keogh said they needed the computer to run algorithms which can estimate ocean productivity from satellite measurements.

Future projections (Graphic supplied)

Future projections (Graphic supplied)

What surprised the researchers the most was how much ocean productivity had declined over the past 26 years, “particularly when we looked at the trends from the algorithms, which are considered the most accurate”.

Ocean productivity is however not declining everywhere, Thomalla noted. “The ocean is patchy, and there are some areas where productivity is increasing, but when we average it across the global ocean, it is decreasing.

“If we zoom in on the African coastline, for example, we can see large declining trends in ocean productivity inshore, relative to the smaller increasing trends seen in open ocean waters further offshore.”

Ryan-Keogh added that more specific studies would be needed to understand the causes of the decline around South Africa’s coastline as it has two very different ecosystems — the Agulhas region and Benguela region, which have unique and different properties.

“However, what we do know is that temperature has been increasing in South African coastal waters and this is the most likely cause for these declines in ocean productivity.”

With the launch of the Plankton Manifesto last year, the role of phytoplankton in the sustainability of the planet is receiving increasing attention. Phytoplankton are under threat and this manifesto calls for immediate global recognition and an action plan to protect these vital organisms.

The manifesto is the result of a collaborative effort led by the United Nations Global Compact, that involved 30 international experts from leading institutions and industries worldwide, including South Africa.

Phytoplankton are immensely important organisms for the planet — without them there can be no functioning ocean ecosystem.

“If we were to sum up all of the photosynthesis that occurs on our planet, 50% comes from plants on land while the other 50% comes from phytoplankton,” Ryan-Keogh said.

“This 50-50 split is remarkable especially if you consider that, if we were to sum up the weight of all plants on land and phytoplankton, plants on land make up 99% of this total weight whereas phytoplankton only make up 1%.”

The Plankton Manifesto, he said, is a long overdue call to action to protect these crucial organisms. “We need to protect their functioning and their biodiversity, to maintain their role in sustaining the global ocean ecosystem.

“We need endorsement of this manifesto to be ratified by the United Nations,” he said, adding this would help raise awareness and provide opportunities for researchers to secure research funding to continue studying them.

The study is a call to attention, Thomalla added. “Our climate models are currently underestimating the future change in ocean productivity. These global declines will have ramifications for the ocean carbon cycle and marine ecosystems, affecting the trophic system that underpins biodiversity, fisheries and the marine resources on which humans rely.”

One key finding from the study is that the decline in ocean productivity will probably be different, depending upon which efforts are made to reduce climate change, given that increasing temperatures emerged as the most likely cause of the deterioration.

“If we do not implement any mitigation, then we could be looking at 3°C to 4°C temperature increases and very large declines in ocean productivity,” said Ryan-Keogh.

“However, if we implement a high mitigation strategy, reducing CO2 emissions to net zero, then the temperature increase could be close to Paris Climate Accord’s of 1.5°C, and we should not see as large a decline.”

Appropriate climate action is needed from world governments and industries, where they pledge to reduce carbon dioxide emissions significantly, he said, adding: “We need climate financing to be secured so that developing nations can transition to green economies.”