Brutal extermination: A painting of Jan van Riebeeck with his men at the Cape of Good Hope in the 17th century. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

The Constitution is our book of redemption.

Once lauded for its promise, the Constitution has been betrayed by the ruling elite and their progenies. But that is not why I write this.

The Constitution recognises the “injustices of the past” and undertakes to correct them. But what is the Constitution talking about when it refers to “injustices”? And where did it come from? What were its founding influences? Why should we stand by it, even as powerful political forces seek to undermine its spirit? One of the reasons is our collective histories and the history of the Constitution itself. Although there is much to contest here, let us begin the work of excavation of the forgotten origins of constitutional thought.

The Dutch engaged in brutal wars of extermination against the indigenous people of today’s Western Cape, but the British did so on a larger scale — and with greater intensity — against the brown-skinned and flat-nosed inhabitants of the Eastern Cape. Recent books have shone a spotlight on the injustices caused to the isiXhosa-speaking peoples of the Eastern Cape in the wars of dispossession that took place at the end of the 18th century and most of the 19th century. John Laband’s The Land Wars: The Dispossession of the Khoisan and AmaXhosa in the Cape Colony is one such book. During those wars, the British empire accumulated vast amounts of wealth by dispossessing the native people of theirs. Territorial possession remains the most visible sign and legacy of those wars.

It has not been easy for the ANC government to undo the racial disparities in land ownership. That is why today most agriculturally productive land is still in the hands of white people or white-controlled entities. By contrast, save for a tiny sliver of the fortunate few, African people are spectators in the land game.

As more light is shed on the historical plight of the Xhosa people, there is a risk of marginalisation of another group of indigenous people, the Khoikhoi and the San of the Cape. The Constitution’s reference to “the injustices of the past” recognises their loss too. The Lie of 1652: A Decolonised History of Land by Patric Tariq Mellet attempts to fill the void of memory of the demise of the Khoikhoi and the San people.

Yet the sheer vastness of the lost historical record may prove this to be an unfillable void — the Constitution’s promise of “healing the divisions of the past” may be incapable of achievement, simply because we do not know enough about how an entire people disappeared. In a history written in blood, it is not easy to know where to start. Because there is no single past, the Constitution’s idea of past injustices requires an excavation of multiple pasts.

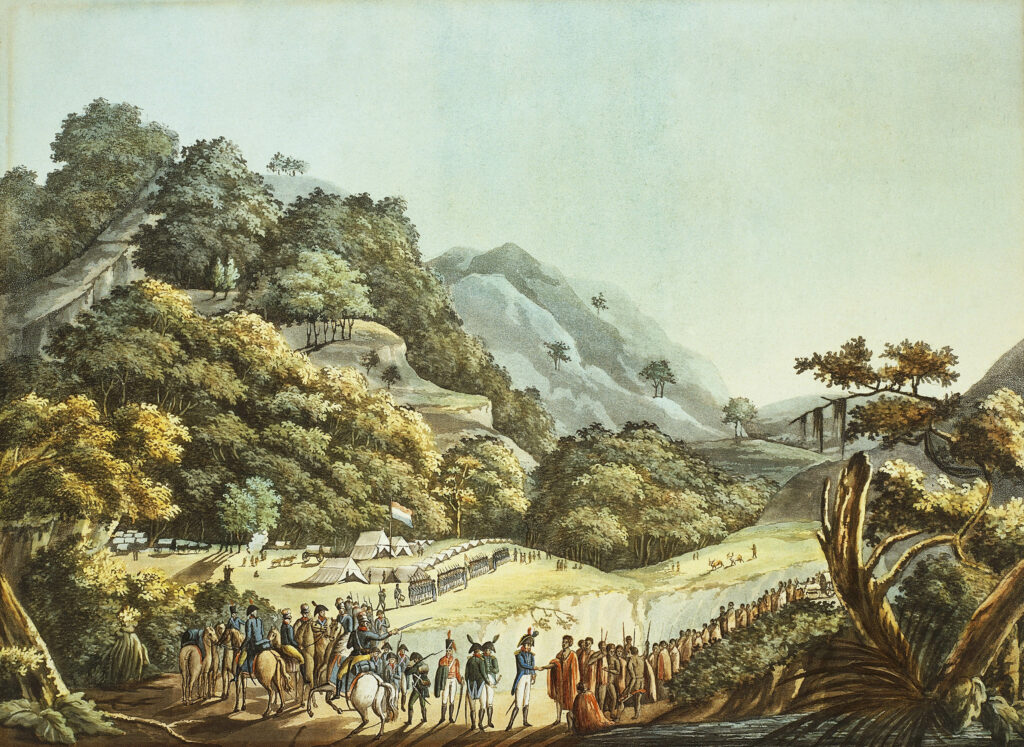

A watercolour depicting Dutch governor Jan Willem Janssens meeting the leaders of the Hottentots in1803. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

A watercolour depicting Dutch governor Jan Willem Janssens meeting the leaders of the Hottentots in1803. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Perhaps the most notorious of the Dutch settlers was Jan van Riebeeck, the commander of the Dutch East India Company and one-time governor of the Cape. A few months after his arrival at the Cape in 1652 he would note in his diary: “The Khoikhoi had come within a short distance of his fort with thousands of cattle and sheep.” He felt “vexed” at the sight of so many fine herds of cattle and at his inability to buy them.

His plan, however, was not to buy them, but to take them by compulsion. With only 150 men he could confiscate 11 000 cattle “without danger of losing one man, and many savages might be taken without resistance, in order to be sent as slaves to India, as they will always come to us unarmed”.

For 100 years thereafter, the Dutch plundered the villages of the Khoikhoi, stealing their cattle, enslaving the population, murdering children, and imposing total political control over the area.

It has been said that the demise of the Khoikhoi population is to be ascribed to the smallpox epidemic of 1713. This, however, is not the full picture. By the late 1700s there remained a sizeable population of the Khoikhoi and the San people in the Cape. Many of them were, at that stage, in the servitude of the Dutch. The remaining, independent population, would be destroyed by Dutch bayonets and guns.

In 1774 the Dutch government in the Cape gave an order to seize or kill “the Bushmen or wandering Hottentots”. No time was wasted by the Dutch commandos — a rag-tag army of “boors”, as they called themselves — in carrying this out. They murdered people, stole their possessions and destroyed what they could not take. They sought to take “the Bushmen” by surprise; “to come upon them at night, or by early dawn of day, and to begin the work of slaughter before their destined victims had time to arm themselves or to make their escape”.

The numbers of the dead were numerous. For instance, in September 1774 a “boor commando” shot and killed 96 San people and took their women and children as prisoners, distributing them among the Dutch for slavery. Another commando murdered 142 San people, taking captive more than 100 women and, in the course of doing so, put to death all of the men.

The cruelty was not isolated. In 1787 two field-cornets reported to the Dutch administration in the Cape that they had killed 67 “Bushmen, but they could not kill more”, because they were short of powder and lead. In their report, they noted that the San “live in the mountains like baboons; when they fire 50 or 100 times before we kill them: we, therefore, most humbly apply to you to send us 600 pounds of gunpowder, and 1 200 pounds of lead”.

Amid the barbarism of the whites of the Cape, European Christian missionaries were proselytising, telling the native people to turn to God, repent and “their sins would be forgiven [and] the doors of heaven open up”. Christianity served only to open further social cleavages among the Khoikhoi. Those who accepted Christianity were treated as enemies. One Khoikhoi declared that “if any Khoikhoi left to become a Christian they dare not return, or they would be murdered”. The deprivation of their land and robbery of their cattle by Europeans had turned them to “a life of savage, a life of plunder”.

By 1806 the British government had extended its sphere of influence, placing the Cape under British rule. In law, it banned slavery. In reality, the hunting, the murder and the enslavement of the Khoikhoi did not abate. The Dutch were now required to report to the government of the Cape of Good Hope.

One of them, John A van Wyk, a field-cornet, reported in June 1824 on the acts of the commandos “that have proceeded against the Bushmen in my time”. He could only say that he had “gone out with many commandos, and have killed Bushmen, but never captured any”. Two years earlier another field-cornet, GD Joubert, could not say how many San people his commando had killed, but they had taken “away seven sleeping babies of the Bushmen, and two of the elder children”.

Violence was not the only method to steal land and cattle. Trickery, deception and fraud were part of the story. The Xhosa people experienced this firsthand. A young colonial military officer, John Graham, had been sent to the eastern frontier in 1809. One of his early achievements, in 1812, was the expulsion of the Xhosa under their chief, Ndlambe, from the Zuurveld, a stretch of land between the Sundays River and the Fish River, part of the land that was allocated to some 5 000 British settlers in 1820. Some 20 000 cattle were confiscated, large fields were burned and Ndlambe’s people sought refuge in the neighbouring land, which was under Ngqika, another Xhosa chief and Ndlambe’s nephew.

Yet the British would also later lay claim to Ngqika’s land.

This is where the fraud was committed. It began in 1816, when the British governor of the Cape, Charles Somerset, conferred on Ngqika the title of “supreme chief” of the Xhosa nation — a title that Ngqika declined. Somerset would not take no for an answer and “recognised” Ngqika as the great chief of all the Xhosa.

Influenced by his proximity to the British, Ngqika’s imaginary power must have gone to his head. He started issuing orders to the other Xhosa chiefs in the surrounding areas. A united force of the Xhosa chiefs would retaliate, routing the phantom Xhosa “king”, taking many cattle and reducing his status to size in 1818.

In turn, Ngqika solicited the help of the British, who invaded Ndlambe’s land. According to Dyani Tshatshu [Jan Tzatzoe], in this battle — known to the Xhosa as Amalinde — the British took “a great many cattle from [Ndlambe’s] tribe, and shot a great many people. Ngqika only got a few old cows, and the government took all the fat cows and the fat oxen.”

The retaliation of Ndlambe’s Xhosa under the influence of their prophet of war and traditional healer, Nxele ka Makhanda, ended in disaster for Ndlambe’s men, who were annihilated in the so-called siege of Grahamstown in 1819. But that year also saw a fraudulent “treaty” being “signed” between Ngqika and Somerset to extend British territory from the Fish River to the Keiskamma River and “cession” of some 10 000km2 to the British.

For years to come, the British would force the Xhosa off valuable property acting in terms of this “treaty”. As well as the intimidating atmosphere at the conclusion of the treaty — the British having proven their military prowess over the Xhosa a few months earlier — the surrounding circumstances put a serious question mark on the legality of the treaty. Ngqika could not write or read. Nor could he speak Dutch or English. The original version of the treaty was written in Dutch.

Wars of dispossession: The British cavalry fighting the Xhosa at the Battle of Gwanga on 8 June 1846. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Wars of dispossession: The British cavalry fighting the Xhosa at the Battle of Gwanga on 8 June 1846. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Although the treaty was verbal, at least from the side of the Xhosa, when Somerset returned to Cape Town, he produced “a very precise and formal document”, which he did not bother to send to Ngqika for either interpretation or “signature”. During the discussions about this treaty, three languages were used — English, Dutch and Xhosa. It is, perhaps, no surprise that, to the day of his death, Ngqika denied ceding territory to the British, as alleged by Somerset.

The greater problem was that Ngqika — as Somerset knew — had no authority to dispose of any part of Xhosa land without the consent of the other chiefs. In Xhosa custom, he had no paramountcy over other chiefs and their territory. Andries Stockenström, the colonial landdrost (or magistrate) from Graaff-Reinet who served as “interpreter” in these negotiations confirmed the source of Ngqika’s authority, based on the fact that “the government had constituted him the supreme authority there”.

However, according to Stockenström, Ngqika “was not the chief of all the tribes. There was a tribe known under the name of Pato, which never was the subject to his control, and that country, also toward the coast, I do not think was ever properly under Ngqika’s dominion.” These were not isolated acts of trickery, taking place some 10 000km away from London. The evidence surrounding the treaty was given at the British House of Commons, but was ignored, and the Cape settlers were allowed to forcibly take land in terms of the treaty.

Tim Keegan in Dr Phillip’s Empire: One Man’s Struggle for Justice in Nineteenth-Century South Africa has masterfully recorded the brutality of the British, as seen through the eyes of Dr John Phillip, a missionary whose sympathies lay with the native people of the Cape.

On 10 August 1836, Phillip could report to the London Missionary Society meeting that extensive districts of the Eastern Cape once occupied by a large, happy pastoral race were left without people, except the occasional white intruder, holding farms of 10 000 acres, enjoying the “grim tranquillity” of empty land.

Phillip’s accounts continued: “If a traveller who had visited South Africa, 25 years ago, were to take his stand on the banks of the Sundays River, and ask what had become of the natives whom he saw there in his former visit; if he would to take his stand again on the Fish River and thus extend his views to Caffraria, he might ask the same question; and were he to take his stand upon the snow mountain, behind Graaff-Reinet, (he would have before him a country containing 40 000 square miles) and ask where were the various tribes that he saw there 25 years ago, no man could tell him where they were.”

The remaining Khoikhoi were put to work, in conditions worse than slavery. Slave laws were not extended to them. This was the source of their suffering. The irony was that formerly enslaved people had legal recourse. They could report the cruelty of their masters, and, in a few instances, obtain legal redress.

The Khoikhoi, the San, the native people of the Eastern Cape could not legally be enslaved but could be treated worse than enslaved people, with no legal protection. They were the subject of vagrancy laws and the pass laws, which imposed restrictions on movement, unless it was for work purposes. As the wars of political and economic conquest against the Xhosa continued, the Khoikhoi and the San of the Cape were not actually vanquished, but exterminated.

The big lie of history has been to blame the smallpox epidemic of 1713 as the sole cause of the decline and disappearance of the Khoikhoi and San populations. When we repeat this lie, we sanitise, we bury, we erase the facts of history from our collective imagination. We render hollow the constitutional recognition of “injustices of the past”.

The second half of the 19th century was marked by the ambivalence of British policy towards South Africa. The wars of territorial conquest intensified. Yet, as more territory fell into the hands of the British settlers, official policy towards the native people of the Eastern Cape appeared to change. In the early 1850s, the laws of the Cape were relaxed to allow coloured people the right of franchise. But they had to prove property ownership and meet educational standards.

This was also the period in which large numbers of African children obtained education in Christian missionary schools. Much has been written about the earlier missionary schools as sites of “civilisation”. Yet it is worth noting that, at the beginning, African children were kidnapped and forced to attend these schools. What these children were taught was to embrace a new way of being; a negation of their cultural norms and aspiration towards European sensibilities.

In The Founders: The Origins of the African National Congress and the Struggle for Democracy, André Odendaal makes the point that the intention of native education was to establish a class of enlightened “Black Englishmen” as purveyors of European thought and ideas. However, these schools also produced a generation of the first black intellectual class educated in the same subjects as their British counterparts.

From this class emerged the founders of the ANC, launched in 1912, as a platform to unite all African people, across tribal identities — in fact, the establishment of the ANC marked the negation of tribal identities and the forging of a new Black, nationalist identity. No longer would African people resist white aggression in their tribal enclaves; they would do so as a single, Black united force.

The national identity was reflected in the founding documents and in the composition of the leadership of congress. Although the Berlin Conference had created boundaries in Africa by 1884, by 1912 the ANC was already acting to undermine these boundaries. The pool from which it drew its leadership recognised no such boundaries — leaders from Zambia, Botswana, Malawi would become part of the nascent political movement.

The ANC contested South Africa’s founding doctrine of racial segregation, entrenched in documents like the Treaty of Vereeniging, the South African Act of 1909 and the Native Land Act of 1913. What they had in mind was a radically different conception of South Africa; one that had to accommodate all its races. Notably, notwithstanding their experiences of conquest and domination, South Africa’s future, they reasoned, was based on the accommodation of everyone, without regard to race.

An enduring feature of the dream of the founding generation of the ANC was to end racial inequality. This had to be achieved through the Bill of Rights. Hence, in 1923, the ANC adopted the first Bill of Rights for South Africa. Ironically, this document incorporated the vision of equality as espoused by an arch colonialist Cecil John Rhodes under the slogan: “equality for all civilised man south of the Zambesi”.

The adoption of a Bill of Rights was a profound moment.

Some five years earlier, under the guidance of one of its most able members, Richard Msimang, the ANC had formulated its own constitution. As testament to his commitment to constitutional government, by the late 1930s Msimang would be described as a “a great lawyer” and “a real constitutionalist”. The constitution of the ANC was a model for a future South Africa. It borrowed the Westminster style of government, comprising the executive and a parliament, and included a senate drawn from chiefs and traditional leaders.

The ideas of a constitution, the Bill of Rights and equality remained part of the folklore of the ANC for much of its early 20th –century thinking. Aggressive Afrikaner nationalism became the order of the day from the 1920s, as the British government adopted a policy of appeasement towards the Afrikaners, after the adoption of the Balfour Declaration in 1917.

This meant the hegemony of white views, as the Afrikaners sought to impose their language, culture and promote their economic position to place themselves on par with their English counterparts. Africans were not forgotten as such; however, they were not treated as autonomous political actors, but as subjects of political control.

This period also saw the consolidation of capitalism driven by global mining interests, creating a class system in which the workers were African and mining bosses and the managerial class were white. But there was also an emerging Black professional strata of teachers, doctors, lawyers, journalists and businessmen.

Self-determination: A local takes in the lie of the land in the then Transkei in 1955. (Three Lions/Getty Images)

Self-determination: A local takes in the lie of the land in the then Transkei in 1955. (Three Lions/Getty Images)

The dream that inspired the founding of the ANC lived on, even as the ANC organisationally faltered to near extinction during the disastrous presidency of Pixley ka Isaka Seme between 1930 to 1937, as noted by Bongani Ngqulunga in his book The Man Who Founded the ANC: A Biography of Pixley ka Isaka Seme. World War II (1939 to 1945), taking place primarily in Europe, gave a fresh, although deceptive impetus for the possibility of African freedom. The Atlantic Charter of 1941, drawn between the British and the Americans as a vision of the post-world war European society, gave a temporary hope to Africans across the world.

The main idea of the Atlantic Charter was self-determination. Sir Winston Churchill, British prime minister and one of the main proponents of the Atlantic Charter, was keen to extend the Charter’s reach to all European societies that were liberated from Nazi rule. Here, in South Africa one of the most thoughtful men of the time, Dr Alfred Bitini Xuma sought to theorise how the principles of the Atlantic Charter could apply to the situation of the oppressed African people of South Africa.

Xuma’s vision led to the preparation of the Africans’ Claims document, in which a statement of the Bill of Rights for Africans was contained. Although it was much more expansive than any document that had ever previously been produced by the ANC, the African Claims continued a tradition of commitment to constitutional government, the Bill of Rights and the principle of equality, all of which were foundational to the ANC in 1912.

The Africans’ Claims document, produced in 1943, was a clear vision for a new South Africa after the end of racial discrimination. Voting would be extended to all adults, regardless of race. There would be a right to vote and to be elected to parliament, provincial councils and other representative institutions for all. The courts would dispense equal justice to all. There would be freedom of movement and residence. Restrictive laws, such as the Native Land Act, would be scrapped. There would be the right of freedom of the press. The right to the sanctity and inviolability of the home would be guaranteed to every family.

Everyone could own, buy, hire or lease and occupy land, without any restrictions. There would be a right to engage in any occupation, trade or profession without discrimination. Employment in the public service would be open to all. Every child would have the right to “free and compulsory education”. Every child would be entitled to admission to technical schools, universities and other institutions of higher learning. There would also be equal pay for equal work and equal opportunity. Unfair policies and practices in employment would be abolished.

The African Bill of Rights, as the document came to be known, has not been as popular as the Freedom Charter of 1955. Yet the Charter’s spirit lies in the African Bill of Rights. Arguably, the most important declaration of the Freedom Charter is that, “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, Black and White, and that no government can justly claim authority unless it is based on the will of all the people.”

This was the proposal of the African Bill of Rights, flowing from the 1923 Bill of Rights, itself a founding idea of the ANC. The Freedom Charter has weathered many political storms. The National Party once claimed the charter was a communist document. However, the moving spirit behind the Charter, Professor ZK Mathews, refuted the charge of the communist character of the Charter. According to him, the Charter was an extension of the African Bill of Rights. Its role was to refine the African Bill of Rights in the light of the National Party aggression since 1948 and to explain the conditions of government in a free, united and democratic South Africa.

The Charter repeated many of the statements of rights contained in the African Bill of Rights. Unlike the Africans Claims, which placed emphasis on individual liberties, the Freedom Charter’s prime occupation was the economic sphere. It proclaimed that the “national wealth of our country, the heritage of all South Africans shall be restored to the people”.

The mineral wealth, beneath the soil, the banks and monopoly industry “shall be transferred to the ownership of the people as a whole”. Industry and trade would be controlled to assist the well-being of the people. The land would be “redivided amongst those who work it”. There would be work and security. Men and women of all races would “receive equal pay for equal work”.

The Charter promised “houses, security and comfort and to use “unused housing space” for homeless people. It would provide free medical care and hospitalisation to all people “with special care for mothers and young children”. Slums would be demolished and new suburbs with transport, roads, lighting, playing fields, creches and social centres built. Orphans, the aged, the disabled and the sick would be cared for by the state.

A combination of the social and economic aims of the Charter and the individual liberties of the Africans’ Claims would form the bedrock of the ANC’s late 20th-century liberation rhetoric. By the early 1990s, the collapse of the whites-only regime was inevitable. But what would replace it was still contentious.

For its part, and to an argument I made in The Land is Ours: Black Lawyers and the Birth of Constitutionalism in South Africa, the ANC returned to its roots. It would rekindle the spirit of the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, universal franchise, a government based on the will of the people and a commitment to social and economic justice. These ideas would be the epicentre of a new constitutional vision, based on the popular will of the majority.

More still had to be done.

The political power of the majority would be restrained by the power of the law. A new idea of constitutional supremacy entered the lexicon of the ANC. This was not hard to embrace, even as communist dogma had some influence in some of the policies of the time. Experiences of unrestrained, despotic white governments for 350 years could not be forgotten. Although the judges were unelected, they were seen as an essential check on the power of the elected government: hence, the foundation of the Constitution is the rule of law.

In these days where the promise of the Constitution stands betrayed, it is easy to ask if we should turn our backs on constitutionalism. Yet, if we take a longer, wider historical trajectory we can see that our Constitution was written in blood. We can see that the phrase “injustices of the past” is not a legal slogan. Instead, it is a reminder of the land that was confiscated by war; an affirmation of the significance of the cattle which were stolen by European invaders. The Constitution is the living spirit of the countless number of Khoikhoi and San children whose little skulls were smashed against the unforgiving rocks of the mountains of the Cape.

When all is said and done, the Constitution embodies multiple, painful pasts. These are the “injustices of the past” to which it pays homage. The founders of constitutional thought — Pixley ka Isaka Seme, Dr Alfred Bitini Xuma, Alfred Mangena, Richard Msimang and Charlotte Maxeke — knew these injustices first hand, yet their views were to confront injustice with justice.

Their intellectual heritage has often been overlooked in favour of recent influences of the 1980s, with people from that era having been given a pre-eminent role in introducing constitutional thought to South Africa. But by recalling the true origins of constitutionalism, we can make sense of the Constitution’s promise. The Constitution can, perhaps once again, play its redemptive role — helping us to navigate the treacherous terrain of our present, uncertain times.