Double trouble: Water pipes lie around the troubled Vuwani area in Limpopo waiting to be installed. The Vhembe municipality is in financial difficulty yet has been charged with servicing Vuwani. Photo: Oupa Nkosi

Last week, a delegation from the United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Social and Environmental Compliance Unit travelled to the Vhembe district to meet residents and key stakeholders about the developmental and environmental impacts of the Musina-Makhado Special Economic Zone (MMSEZ).

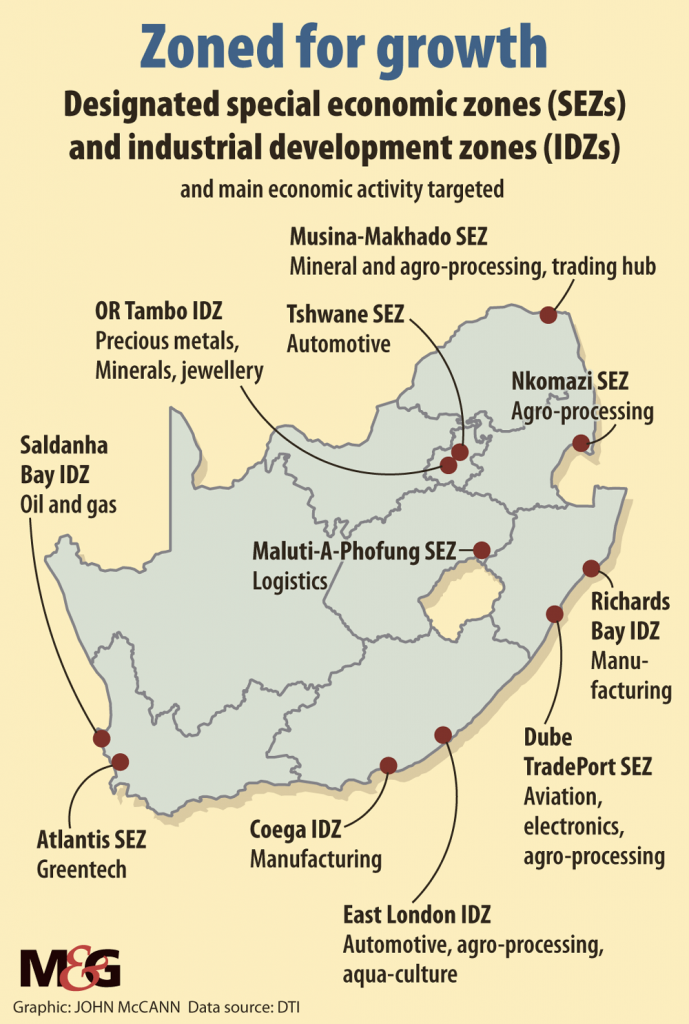

Special economic zones are geographically designated areas set aside for specific economic activities. They are growth engines towards a government’s objectives of industrialisation, regional development and employment creation.

The MMSEZ’s notoriety arises from many complex sources. Perhaps the most obvious problem with it is its developmental footprint in the final environmental authority from the Limpopo department of environment and tourism. The zone has glaring flaws. There is a coal-fired power plant to provide energy for metallurgical extractive industries and a steel plant. These industries already have sustainability question marks, enhanced by the water scarcity of the region and its world heritage biodiversity status.

The UNDP has a memorandum of understanding with this zone, which has raised the ire of a number of environmental organisations and social movements. The Centre for Environmental Rights and the Centre for Applied Legal Studies have provided legal rights-based support on environmental and livelihood issues to affected people. The memorandum is seen as an endorsement of the sustainability of the zone while glossing over its many environmental and livelihood problems.

A flawed process

Interested and affected parties that have followed the evolution of the zone’s deeply flawed environmental impact assessment (EIA) process have raised questions relating to biodiversity and climate change. The major flaws include poor participation processes and missing climate and biodiversity reports. These concerns have fallen on deaf ears at the Limpopo Economic Development Agency. The zone is championed as the developmental salvation of Limpopo and the source of long-term employment creation in a province with the lowest rates in the country.

The UN delegation were prompted into action by written complaints to their unit. The complaints were lodged after an open letter from the UNDP South Africa’s representative, Ayodele Odusola, to those parties who questioned the sustainability endorsement of the memorandum. Odusola, in the letter, states, “… UNDP’s interest in engaging with the zone is part of its efforts to promote socio-economic development that is environmentally and socially sustainable to contribute towards overcoming South Africa’s triple development challenge”.

Odusola further states that the zone’s initiative is part of a larger regional and continental plan to link trade, investment and infrastructure development in the region. The African Continental Free Trade Agreement is also noted as a major aspect of the zone’s sustainability. This is a critical African initiative but the background to the zone’s link to China’s Belt and Road Initiative to reroute South, Southern and African trade towards China is not well understood.

The development trajectory of the zone is even more confusing when one considers how, in the same letter, Odusola states, “The UNDP has been given assurances, including in the form of a public statement, that all coal-fired power generation plants have been replaced by solar and hydrogen energy facilities which reduce greenhouse gas emissions.”

The April announcement by the chair of the zone that it would no longer need energy from the coal plant, despite the final environmental authorisation ruling out solar energy, calling it scientifically unfeasible. This is clearly an attempt to avert the controversy about the climate change critique of the zone. The final approved environmental authorisation states bluntly (on page 725), “… in order to provide baseload power to the metallurgical off-takers, the MMSEZ’s application would require at least 8 – 10 hours of battery storage. That scale of battery storage system is physically constrained and requires excessive capex … Based on the above, it is clear that large scale baseload power generation from solar plus storage is not yet feasible or economically viable for the MMSEZ’s purposes.”

More dirty energy

Recent interviews with stakeholders and residents show that a number of mothballed coal mines have had their environmental authorisations resuscitated, despite previous environmental legal action. Two environmentally controversial collieries owned by MC Mining (previously Coal of Africa) are re-opening in the next couple of months and Vele mine has opened job applications, facilitated by the Musina municipality.

In a meeting with the Mudimele elders, concern was expressed by their chief that although they had been informed that the Makhado Colliery adjacent to their land would be opening, they had no further information about the operations of the mine. They, together with the agricultural company ZZ2, had the Makhado environmental assessment set aside in 2016, in court action taken by advocate Christo Rheeders on behalf of the Vhembe Stakeholder Minerals Forum. Ironically, Coal of Africa, now rebranded MC Mining, has re-emerged as the mining conglomerate of the province.

The environmental authorisation of the zone is under appeal review by the Centre for Applied Legal Studies, the Living Limpopo and Herd Nature Reserve represented by All Rise Attorneys for Climate and Environmental Change.

MC Mining Corporation’s website explicitly states that the coal mines will supply the zone with its energy needs, making more mockery of the chief executive’s pronouncements that solar energy has been abandoned. The charade continues with Masoga stating late last year in the media that, “one of the appeal grounds by various organisations about the EIA was that we wanted to build a coal-fired power station. We have abandoned it and we are now going to use a combination of Eskom power, solar supported by battery storage and hydrogen.” For a zone this size and based on the need for metallurgical industries, solar energy is simply not feasible.

While the reference to Eskom supplying the zone with power may have us all clutching our sides hysterically, or in an even deeper state of depression about load-shedding and no end to the crisis, it is clear that the energy planning is both flimsy and dodgy.

Another crucial issue is the northern site in Musina. The chief executive refers to it as part of the zone but it is not. The environmental authorisation confirms this. An entire gazetting process is needed to get it as part of the zone. The EIA for the northern (Antonvilla) site simply authorises a warehouse, a farmers’ market and light industry.

Startlingly though, Masoga has started to refer to the Northern “SEZ” as a site for the metallurgical companies and possibly even mines. But we have recently discovered that it was never gazetted. So none of the zone’s perks, which draw the funders, apply. It is hard to figure out in the social media, where the lies end and the truth begins, but to the UN team, it’s a heads up.The South African office will have to tread carefully on our government’s promises or the damage to the UN’s reputation is undisputedly collateral damage.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.