A scaled-down labour inspectorate will leave vulnerable workers at the mercy of ‘unscrupulous employers’

Budget cuts to the department of labour’s inspectorate have sparked concerns that “unscrupulous employers” will go unchecked while workplace safety deteriorates.

All eyes have been on the Commission for Conciliation, Mediation and Arbitration (CCMA) since it emerged it will have R600-million slashed from its budget over the next three years.

But the CCMA is not the only corner of the department concerned about the effect budget cuts will have on day-to-day operations. The labour inspectorate — tasked with weeding out employers who fail to keep their workers safe — had more than R63-million cut from its budget last year. And it won’t be getting that full amount back in the near future.

Labour inspectors visit workplaces to investigate complaints by workers and to make sure they comply with labour laws, like the Occupational Health and Safety Act and the Basic Conditions of Employment Act.

In 2019, the Mail & Guardian reported on how the inspectorate helped bust a blanket factory in the south of Johannesburg called Beautiful City. Inspectors found that workers, some of them under the age of 15, were forced to work in dreadful conditions and earned only R6.50 an hour. One worker had one of his fingers cut off, another had his hand burned and a third was losing his eyesight.

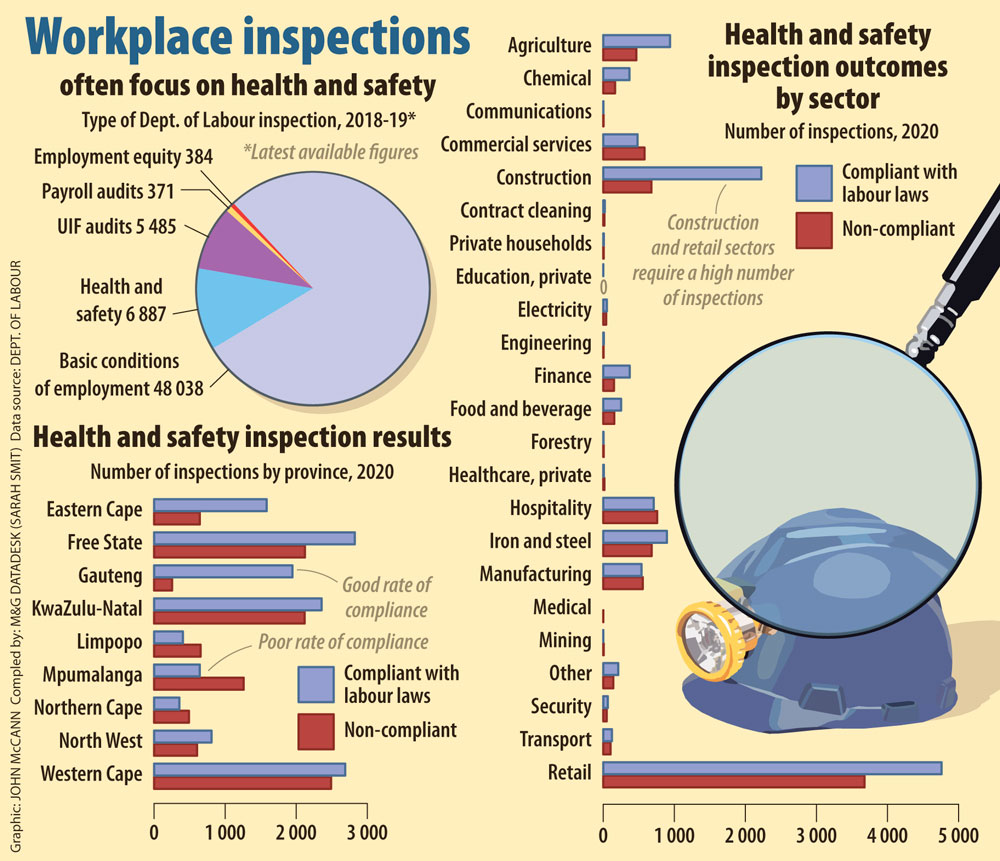

When Covid-19 hit South Africa’s shores a year ago, the inspectorate received a wave of complaints by workers that their bosses were not complying with pandemic-related protocols put in place to stop the spread of the virus in the workplace. Inspectors conducted 24 252 health and safety checks and the overall compliance rate was only 56%.

Despite receiving a boost to its budget last year, the department’s director general Thobile Lamati said the subsequent cut may mean that inspections will have to be scaled down.

Lamati said though the initial budget cuts were not felt in 2021 — because of decreased travel costs — this will likely change as the economy re-opens and inspectors are expected to work at their full capacity. Last year, the department decided to reduce its inspection targets by 15%.

In the 2019-20 reporting period, the department’s target was to inspect 220 692 workplaces in total. After reducing its target, it would have been expected to conduct 187 588 inspections.

“The implication of that is we will visit fewer workplaces,” Lamati said, adding that vulnerable workers will be exposed to “unscrupulous employers” as a result.

Future financial restrictions also means that less inspectors will be able to go out in the field and the department will have to scale down its outreach campaigns, Lamati said.

The department had plans to train more inspectors specialising in enforcing employment equity targets, set to ensure all workers receive equal opportunities and that they aren’t discriminated against.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Forthcoming amendments to the Employment Equity Bill empower the department to exclude non-compliant businesses from doing business with the state. But there are currently only nine inspectors in the whole country who specialise in employment equity.

Prior to the pandemic, the department advertised 500 new inspector posts. But according to the deputy director general in charge of inspection and enforcement services, Aggy Moiloa, not all these inspectors are out in the field yet.

According to the treasury’s budget vote document for the department, there will also be personnel cuts to the inspectorate in the medium term. By the 2023-24 financial year, there will be 112 fewer people working for inspection and enforcement services.

To report an employer who is breaking labour laws, workers can contact their nearest labour centre or provincial inspector.

[/membership]