What’s driving anti-immigrant healthcare blockades? Sharon Ekambaram from Lawyers for Human Rights says it's everything from the sky-high cost of Zimbabwean passports and corruption to South Africa’s institutionalised xenophobia — and a growing global intolerance of migrants. (Bhekisisa team)

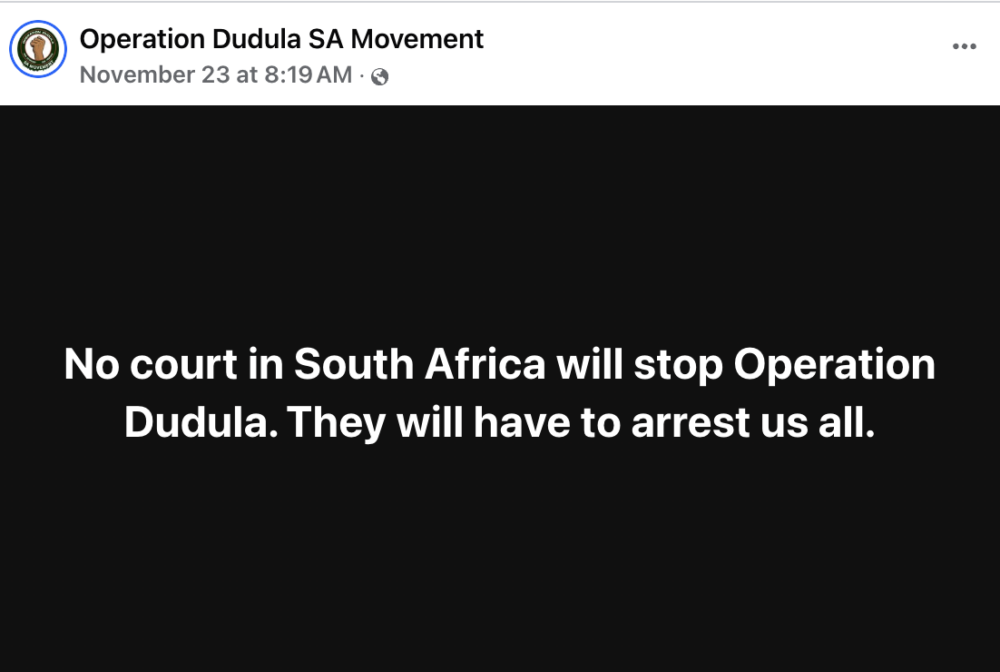

Two days before health rights groups the Treatment Action Campaign, Medecins Sans Frontieres and Kopanang Action Against Xenophobia launched an application at the South Gauteng High Court on November 25, seeking an order to force the state to ensure safe access to hospitals and clinics, and remove anyone trying to keep people out, the vigilantes behind the healthcare blockades threw up their middle finger to justice.

“No court in South Africa will stop Operation Dudula,” the group’s Facebook post read. “They will have to arrest us all.”

Based on the Gauteng High Court’s most recent ruling on Thursday (4 December), the police may have to do just that.

The previous ruling on 4 November interdicted the xenophobic group, Operation Dudula, from blocking foreign nationals from their constitutional right to healthcare, a right that applies to everyone living in South Africa.

For months, vigilantes have been harassing and intimidating those they deem foreign nationals, demanding ID books and passports and blocking them from entering hospitals and clinics.

Section27, acting for Médecins Sans Frontières, Treatment Action Campaign and Kopanang Africa Against Xenophobia, headed back to court on 25 November, because problems at particularly the Yeoville and Rosettenville clinics in Johannesburg have remained.

Judge Stuart Wilson ordered the Yeoville and Rosettenville clinics in Johannesburg, the City of Johannesburg, Gauteng and national health departments and police to remove anyone hindering access to foreign nationals at the two clinics, make sure there are enough trained security personnel at all access points to ensure that the court’s order is carried out, and to, within five days of the court ruling, post notices at all entries to the clinics that read:

“No unauthorised person may obstruct or hinder physical access to this clinic or the provision of healthcare services within the clinic. Any person violating this instruction will be removed from the premises and its surrounds and reported to the police.”

The same institutions also have to report all incidents and unauthorised people on the premises of the Yeoville and Rosettenville clinics to the SA Police Service (SAPS) and take “all reasonable steps” to identify them.

The National Health Act says that anyone not on medical aid is entitled to free primary healthcare services (generally services offered at clinics), regardless of nationality; pregnant and breastfeeding women, and children under the age of six are entitled to free healthcare services at both clinics and at hospitals.

Refugees, asylum seekers and undocumented people from the Southern African Development Community, which includes 16 member countries in the region, are entitled to an income-based evaluation to determine the extent of subsidisation they can get from hospitals.

“Xenophobia is one of the greatest threats to democracy and human rights we presently face,” Judge Wilson warned in his ruling.

“Leaving aside the fact that it feeds on that most toxic of human instincts: the hatred of the others; forgetting that it is animated by the fantasy that the presence of foreign nationals in South Africa immiserates the lives of its citizens; and overlooking that, in its practiced form, it is merely another kind of racism … the problem with xenophobia is its misdirection.”

Sharon Ekambaram, head of the refugees and migrants rights project at Lawyers for Human Rights, likens the illegal demands for proof of citizenship — which includes the 4.4-million South Africans over the age of 16 without IDs — to the “dompas system under apartheid”.

Ekambaram, who has been an activist since the 1980s, spoke to Mia Malan on Bhekisisa’s monthly TV programme, Health Beat, about what’s driving the blockades and emboldening groups like Operation Dudula. This is an edited version of their conversation.

Mia Malan (MM): Why is it so difficult for asylum seekers [someone who has applied for refugee protection] to get documents in South Africa?

Sharon Ekambaram (SE): The asylum system is in absolute crisis, and it is contributing to institutionalised xenophobia, where it’s assumed that any foreign national coming from the African continent is lying about their reasons for coming to the country. So people coming from the DRC, from Somalia, even people coming from Gaza, who cannot access the asylum system, remain undocumented and at risk of being arrested.

For those coming from the neighbouring countries, in particular in Zimbabwe, it costs about $250 [about R4 300] to get or renew their passport. So people who come to South Africa, who are often working in the informal sector, cannot afford that document [which would show their legal status in the country]. The South African government should be engaging with the Zimbabwean government to discuss this. People have to have passports and they have to be stamped [by South African authorities] so they’re [legal] in the country.

But we [also] know that there are over 700 000 South Africans, who’ve had their IDs blocked or who are struggling to get IDs. So it was just an arbitrary process of refusing people simply because they didn’t have a document.

[Editors: The 700 000 refers to a January 2024 case brought by Lawyers for Human Rights about “ID blocking”, which was found by the court to be unconstitutional. The department of home affairs told Parliament in November that there are more than 4.4-million South Africans 16 years and above who do not have IDs.]

MM: Do most healthcare workers know the healthcare rights of foreigners?

SE: We worked in a partnership with Section27 to engage with government health officials, particularly in Gauteng, to ensure that hospitals obey the law of access to treatment for pregnant mothers, lactating mothers and children under the age of six, and to ensure that every hospital has a circular informing healthcare workers of this.

What we are witnessing [in healthcare] is the institutionalised xenophobia where healthcare workers and the administrative staff of hospitals and clinics have a prejudice against patients who are migrants.

MM: You have taken people like the premier of Limpopo, Phophi Ramathuba, to the Health Professions Council, when she spoke very harshly to a female Zimbabwean patient, which was circulated on social media.

SE: Phophi Ramathuba is, first and foremost, a medical doctor, and she has taken a Hippocratic oath about how she will conduct herself as a medical doctor. The Health Professions Council found that she had broken that oath and was acting in a manner that contravened the behaviour of a medical doctor. She challenged that finding and it has been going on for two or three years because she [continuously] postpones the hearings when they sit down, and is never available.

MM: How have other leaders in the health field, in the government, influenced this behaviour?

SE: Health department minister Aaron Motsoaledi scapegoats migrants, making unsubstantiated statements that our public facilities are flooded by migrants. Do the maths. There’s about 3-million foreign nationals in our country and we have a population of 65-million people. It’s not plausible to have a tiny percentage “flood” public hospitals.

[Editors: StatsSA’s latest data puts South Africa’s population at 63.1-million and the number of migrants at 2.4-million, noting “census data may fail to capture the recent dynamic and often rapid changes in migration patterns, leading to an underrepresentation of recent or temporary migration events”.]

By scapegoating migrants our attention is detracted from the corruption and mismanagement that is taking place, starting in Gauteng. Instead of talking about the migrants, we should be holding this government to account for addressing rampant corruption, in particular in the health department.

MM: How have these kinds of comments about foreigners, which leads to violence and exclusion, become normalised?

SE: With people like [US President] Trump coming into power, it has emboldened xenophobes and reactionary elements who are othering and blaming people, fuelling prejudice because of sexual orientation or being a black person. The level of xenophobic hatred and racism has significantly changed with reactionary leaders like Donald Trump, and across Europe as well.

MM: So what is the biggest policy change that you think we need to see?

SE: We have brilliant policies on health, migrants and refugees. The problem is that we are not holding the government to account to ensure that those policies are enforced and respected, and [are not] allocating proper budgets for public healthcare and quality education.

MM: What would it take to turn the conversation back to dignity and fairness?

SE: We have to go back to organising in communities where people are empowered to understand what is taking place and to take a stand against mismanagement at local government level. We are coming up to local government elections in 2026 and it’s going to be critical for us to make an informed vote and to hold our leaders to account. And we are not doing that, and our democracy is in crisis because of that.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.