During the last years of apartheid, Willem “Ters” Ehlers could feel the political tides turning.

His boss, president PW Botha — who had vehemently defied all calls for reform — was under pressure. Botha’s days of leading his party, and the country, were numbered.

In 1989, Botha met Nelson Mandela in a secret meeting at his Tuynhuys office in Cape Town. Mandela was still in prison at the time. For apartheid stalwarts clinging to their notions of white supremacy, it marked the beginning of the end. The only photo of the meeting was taken by Ehlers.

The fall of apartheid was bad news for Ehlers. A commodore in the South African Navy, he had risen fast to become Botha’s private secretary and aide-de-camp. He was part of the inner circle of an imperial president, which included defence minister Magnus Malan and apartheid assassin and super-spy Craig Williamson.

Ehlers wielded considerable influence and would have had unparalleled insight into the increasingly paranoid and violent regime.

But, as it crumbled, he was soon to be made redundant. What he did next is the subject of a damning new research report by the South African non-profit group Open Secrets, which was released in Johannesburg on Thursday.

Inner circle:

Nelson Mandela

meets president

PW Botha in

Cape Town on 5

July 1989. Photo:

Ters Ehlers

Inner circle:

Nelson Mandela

meets president

PW Botha in

Cape Town on 5

July 1989. Photo:

Ters Ehlers

Dangerous waters

In March 1993, a Greek-flagged ship called the Malo departed from Montenegro and set course for Somalia. Before it could get there, it was boarded and searched by authorities from the Seychelles. In the hold, they found an enormous cache of arms, including 2 500 AK-47s, 6 000 mortar rounds and 5 600 fragmentation grenades.

As Somalia was under a UN arms embargo at the time, the ship was seized and the arms were confiscated.

At first, the Seychelles government said that it wanted to destroy the weapons. But a year later, another, more lucrative option, presented itself — courtesy of Ehlers and his new associates.

In a move straight out of a Graham Greene novel set in the crumbling days of an authoritarian regime, Ehlers had “gone private” and reinvented himself as an arms dealer.

He became part of what Human Rights Watch, in a 2000 report, described as an “old-boy network”, which spanned both national defence and private business in South Africa and drew on experience gained in dodging arms embargoes.

In 1990, one of Ehlers’s first new positions included taking over as managing director of a sanctions-busting front company for the apartheid state, the Seychelles-based GMR. It was named after Giovanni Mario Ricci, an Italian who started the company with the infamous spy Williamson.

Ricci was a close friend and advisor of Seychellois president France-Albert René. Ehlers, for his part, claims to have been close to the presidents of Cote d’Ivoire, Malawi, Uganda, Zaire and Zimbabwe. Between them, Ricci and Ehlers convinced the government not to destroy the Malo’s dangerous cargo, but to sell it. And they had a buyer in mind.

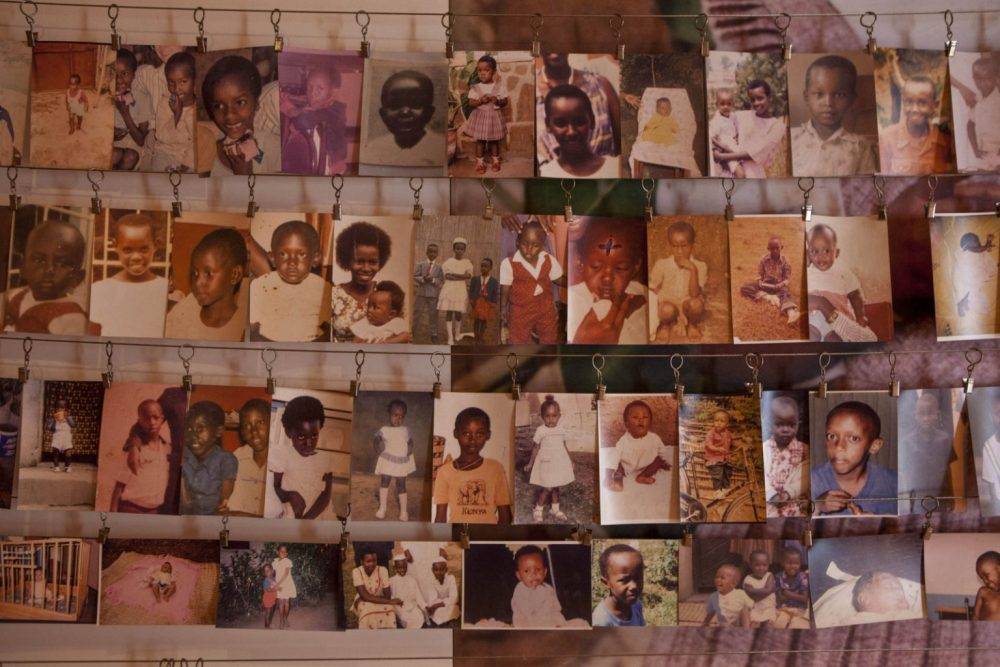

Never forget: Photographs of some of the victims of the Rwandan genocide at the

Kigali Genocide Memorial. Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP via Getty Images

Never forget: Photographs of some of the victims of the Rwandan genocide at the

Kigali Genocide Memorial. Photo: Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP via Getty Images

Arming a genocide

Over a period of 100 days in 1994, beginning on 7 April, the Rwandan government of the time instigated the slaughter of almost 1 million minority Tutsis, moderate Hutus and Twa. Two million would be displaced. Many, many more were maimed, raped and traumatised.

While much of the violence was coordinated on radio stations and involved the Interahamwe — the youth wing of the ruling party — it included neighbours killing neighbours, priests murdering congregants and massacres perpetrated by the government’s army. Machetes and small arms, including rifles, were the weapons of choice in the killing.

Some of those guns had been made in apartheid South Africa, which had supplied an estimated $32 million worth of arms and military equipment to the Rwanda government between 1990 and 1993. At the time, South Africa had the world’s tenth-largest arms manufacturing industry.

Enemy of humanity: Former Rwanda

army Colonel Théoneste Bagosora

(right), the mastermind of the 1994

genocide, was sentenced to life in

prison. Photo: Tony Karumba/AFP via

Getty Images

Enemy of humanity: Former Rwanda

army Colonel Théoneste Bagosora

(right), the mastermind of the 1994

genocide, was sentenced to life in

prison. Photo: Tony Karumba/AFP via

Getty Images

But, as the genocide continued, obtaining more guns became difficult for its perpetrators. In May 1994, the UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo, making it illegal to sell or supply arms to Rwanda.

This did not stop Ehlers, as Open Secrets details meticulously in The Secretary: How Middlemen and Corporations Armed the Rwandan Genocide. The report, which pieces together media interviews, police and witness testimonies and declassified records, concludes that Ehlers played a central role in getting guns from the Malo into the killing fields of Rwanda.

This is how it worked. On 4 June 1994, Colonel Théoneste Bagosora — a Rwandan military officer described by the historian Gérard Prunier as the “general organiser” of the genocide — flew from Johannesburg to the Seychelles. He used the nom de plume “Mr Camille” and Ehlers flew with him.

Together, they negotiated a deal with the Seychelles government to purchase the weapons and send them by plane to Goma, in the east of what was then known as Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo).Two such flights took place, on 16 and 17 June and 18 and 19 June, a period when the bloodletting in Rwanda had not yet abated.

According to another Human Rights Watch report in 1995, the government of Zaire issued an end-user certificate in respect of the arms, but on arrival in Goma, they were handed over for the use of Rwandan government forces in Gisenyi across the border.

Payment for the weapons was made to the Central Bank of the Seychelles, to an account it held at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. In total, $330 000 was deposited there in two separate payments — both made on 17 June 1994 from a Swiss bank account belonging to Ehlers.

A subsequent UN investigation into the funding of the genocide found that Ehlers himself received in excess of $1.3 million for brokering the deal.

Infographic by Open Secrets.

Infographic by Open Secrets.

Bitter fruits

Bagosora was charged and convicted of crimes against humanity by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda and, after spending the rest of his life in prison, died in September 2021. The 75-year-old Ehlers, meanwhile, was tracked down to a comfortable suburban home in the Waterkloof suburb of Pretoria, scenes of murder and rape in Rwanda merely a fragment of a far-away history.

Speaking to Open Secrets, Ehlers described himself as merely a fixer, whose job was to smooth relations and trade between South Africa and countries like Uganda and the Seychelles. He said that he was adept at operating in Africa because he “had contacts” and understood that “when you sell goods in Africa, you have to receive the payment first”.

He said he didn’t know that the guns on the Malo would end up in Rwanda; that he believed they were going to stay in Zaire. Besides, he said, in his estimation the weapons would have only reached Rwanda “when the fight was already over”.

“Obviously I feel very bitter. Inside, my heart cries. Inside, I know that I am not that person,” Ehlers said.

After its exhaustive investigation, Open Secrets concluded that Ehlers ought to be held to account for his actions and will submit a docket containing all relevant evidence to South Africa’s National Prosecuting Authority.

This article first appeared in The Continent, the pan-African weekly newspaper produced in partnership with the Mail & Guardian. It’s designed to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Download your free copy here.

This story was first published by Open Secrets