Gourmet's delight:A special room where the hams are hung to dry in Langhirano near Parma. (Stephano Rellandini, Reuters)

'Come," said the gallant knight, "let us survey this fair city while all are slumbering." So the princess left her bedchamber and followed her lord up spiral stairs and a wooden ladder to a terrace at the very top of the high tower, where … lo, the city of Bologna lay spread below them, and stars twinkled over far peaks.

OK, the knight was my husband, and there was no starlight because a sudden autumnal downpour was signalling an end to the mid-30s summer heat. But though I was in pyjamas (not a silk nightgown), we had no worries about meeting anyone, for we had all 12 storeys of 900-year-old Torre Prendiparte to ourselves.

Built as a stronghold in the 12th century by the powerful Prendiparte family, this is one of a handful of 100 original towers still standing in the ancient heart of Bologna. It was part of a seminary in the 1500s, and a prison in the 1700s, but today it is a super-romantic holiday let.

We'd accepted the heavy 18cm key to our fortress late that afternoon from the owner, Matteo Giovanardi. His father bought the tower in the 1970s, and Matteo made it his home for several years in the Noughties. But ancient properties are money pits, and to keep it he needed to make it pay, so he has created a three-storey suite brimming with atmosphere.

From the small entry hall, wooden steps lead to a cosy living area with a modern shower room built into the two-metre-thick walls. The bedroom is on a mezzanine gallery and the kitchen (with vintage furniture but smart appliances) is one floor up.

The next few storeys are used for parties, concerts and exhibitions (when no one's staying) but levels six to 12 are pretty much bare, with just enough new flooring laid not to frighten nervous visitors. You could sunbathe nude on that roof–total privacy in the middle of town.

The fourth floor was used as a jail in the 1700s, and prisoners' "frescoes" are still visible on the walls. Anyone on bread and water would dream of proper food, but the privation must have been felt keenly by these men. The province of Emilia-Romagna, of which Bologna is the capital, is one of the world's top foodie regions.

Outside the tower walls, citizens would have been eating prosciutto, mortadella, Parmesan cheese, silky egg pasta and bolognese ragu, seasoning their meals with balsamic vinegar from down the road in Modena, and washing it all down with the region's excellent wines.

Given that we had our liberty, and a hire car, it seemed the best use we could make of both was to try as many of these gastronomic delights as possible. So, next day, having breakfasted well on fruit, pastries, bread and coffee in the generously stocked kitchen, we set off on a culinary odyssey.

West of Bologna, along the ancient Roman Via Emilia, is Modena, the name on bottles of dark, syrupy vinegar sold from Sydney to Stockholm.

Most commercial vinegar production happens outside the city, but we got our foodie fix in the covered market, a 1930s design classic, its Liberty-style wrought iron sitting happily amid Renaissance buildings.

Inside, women were expertly perusing fish, sausages, suckling pigs, cheeses and colourful stacks of fruit and veg. At its northeastern edge, Bar Schiavoni is run by two friendly young women who make market produce into more interesting sandwiches than you generally find in this country of sit-down lunches. A hot pinenut-and-raisin roll filled with cold duck, rocket and sliced orange made a perfect lunch, washed down with a glass of white.

Modena's most famous wine is Lambrusco. Yuck, most wine-lovers would probably say, knowing it only as a sweet fizzy plonk. But we headed into the Apennine foothills south of Via Emilia to meet a producer busy improving Lambrusco's reputation. Near the village of Levizzano, Mattia Montanari and family have an organic winery, Opera02, with 21 hectares of vineyard from which they produce dryish, very high-quality Lambruscos, fermented slowly for a fine, long-lasting fizz. It's been a great success, particularly in the United States.

In the past year, they have added what they call a "resort", which is actually a stylish boutique hotel and restaurant. Eight individually designed rooms have colour schemes based on local products: "Cherry" deep red, "Honey" soft browns, "Wine" … you get the idea. Terraces offer sweeping views over what look like Tuscan hills and an infinity pool built with reclaimed wood and stone.

We had joked on approaching Modena that the city would reek of vinegar. It didn't. But you can't escape the smell at Opera02: the bedroom doors open on to a corridor fronting the acetaia, or vinegar loft. Here, 500 barrels sit in groups of six in semi-darkness, busy producing one of the world's favourite condiments.

Manager Roberto explained how at one time every family would have its own acetaia, a battery of six barrels in descending size. At the beginning of the process, the largest is filled with reduced grape juice, which ages for at least a year, with some evaporation. The product is then decanted into the next barrel down–which will be of a different kind of wood, chosen for the flavour it will add – until final fermentation several years later in a container less than half the size of the first. The basic vinegar takes 12 years, the best 25. The first barrel of a set would traditionally be started at the birth of every baby boy, so that by the time he married he would have an established acetaia.

As well as Lambrusco, the region produces other well-structured reds, which smell sweetly of sun-ripened grapes but are smooth and dry to drink.

We enjoyed one with dinner that night in the small town of Castelvetro, where restaurant Locanda del Feudo is run by two charming young brothers, Roberto and Andrea Rossi, who buy from a network of local producers. Six atmospheric suites upstairs have exposed beams, period furniture and views over rooftops and countryside.

Photography by Alessandro Garofalo, Reuters

Photography by Alessandro Garofalo, Reuters

We sipped at a sassoscuro red from local winemaker Vittorio Graziano, savouring its gamut of flavours. Roberto told us the wine was made from 40% malbo gentile grapes, blended with another variety that has grown on these hills for generations, but is unnamed because the small producer can't afford to have its genealogy tested. It made a brilliant partner for a meal that included a souffle with a perfectly runny egg yolk inside, served with asparagus, then tortellini with Parmesan cream and roast and confit pigeon with chard and artichokes.

Further up the Via Emilia is Parma, of ham and cheese fame, where we ogled shop windows full of prosciutti and formaggi of varying maturity. We fully intended to have a healthy vegetarian lunch to counter the rich fare of the night before. In Enoteca Fontana, a delightfully low-key locals' wine bar, we ordered baked courgettes and a dish of beans in parsley and oil–but then reasoned that we just couldn't be lunching in Parma and not indulge, so we added a plate of the eponymous ham to our order, with a glass each of fruity dry Lambrusco.

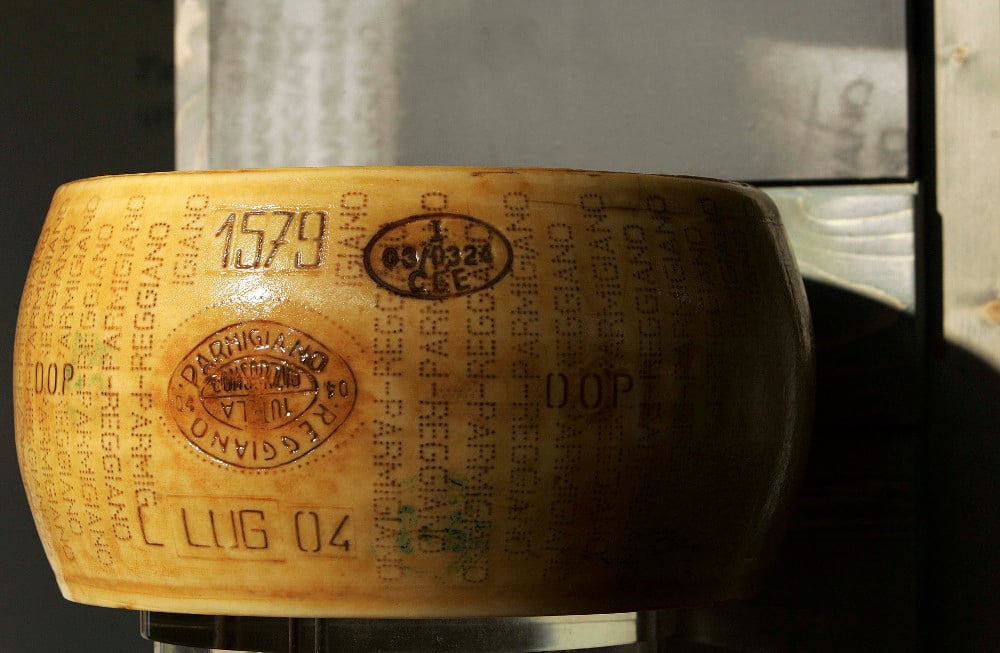

Where Opera02 had been suffused with the smell of vinegar, in the corridors of Antica Corte Pallavicina, on the banks of the Po itself, further north in Polesine Parmense, we couldn't escape the smell of the wheels of Parmesan maturing in the cellars below.

This small castle, built in 1320, was bought as a virtual ruin by chef Massimo Spigaroli and family in 1990. After two decades of restoration, it's now a Michelin-starred restaurant with rooms. The six bedrooms include two suites, each with a bedroom in a corner tower, and they and the guest lounges are furnished with such exquisite period detail you might imagine that those 14th-century marchesi had just popped out.

But the cheese whose aroma was filling our nostrils is not what Antica Corte is known for. Its speciality is a health and safety inspector's nightmare. Classic prosciutto is cured and dried in airy hillside towns here. On the misty Po, whole hams on the bone would rot before they could dry out. The answer was culatello, which means "little bum". The Pallavicina family and others specialised in filleting and curing the tenderest cut, from the pig's rump. It's then wrapped in a pig's bladder (yum!) before being aged in a cellar where damp river air brings in a choice selection of mould spores, which add their unique flavour.

We toured the curing cellars, gazing up at perhaps 6 000 little bums, hearing about the large white Zibello pigs whose haunches these are, and the way the pear-shaped hams are moved around the cellar to pick up different moulds. It's OK, we were assured, one lot of mould is brushed off before another grows. Culatelli are aged for between 16 and 37 months, and many of the oldest were already earmarked for restaurateurs and gourmets the world over. I spotted one with "Alain Ducasse" on the handwritten label, and another with "Principe Carlo"–yes, he of Highgrove has a taste for one of the world's most sought-after cold cuts.

Musing on delicious foods from revolting processes–two-year-old curdled milk on your pasta, anyone – we made for the restaurant, which, unlike the guestrooms, is light and modern, with one wall of glass overlooking water meadows. Our multi-course tasting menu included a plate of different ages of culatello, and it was fascinating to munch down the years. The 18-month-old was delicious, the 27-month we felt we could eat for ever, yet the 37-month was even better, a slight sourness adding extra depth of flavour. Other courses included courgette cream with ricotta, a 50-herb salad, a dish of veal tongues with rice, another of frogs' legs on crushed potatoes, and an unusual iced Parmesan bavarois with celery sorbet.

Sipping selected fine wines with each course, we reminded ourselves that, had we been around in the castle's heyday, the likes of us would not have been eating culatello with the nobles. We'd have been subsisting on bread and turnips, or even banged up in a tower prison if we'd displeased the Pallavicina family.

But in these more egalitarian times we savoured our excellent dinner, and while a tasting menu at €79 a head would only ever be a special treat, you don't need to be a princess to sample it.–© Guardian News & Media 2013