Je suis Charlie is the phrase on everyone’s Twitter handle, Facebook page and politically aware Instagram account. #JeSuisCharlie equals #JeSuisProAllThingsGood – in theory, anyway.

However, #JeNeSuisPasCharlie (I am not Charlie) because, despite disagreeing with the violence, I also view the original phrase as encompassing the idea that those at the top of the food chain can do what they want and we are defending their right to do it, one tweet at a time.

That is why leaders who do not even have freedom of speech in their own countries joined the Parisian march. Where was the #JeSuisCharlie for their own citizens?

Quite simply, their ideas are the powerful ones that mattered enough to rally what is termed “one of the most used hashtags ever”. It has become an “us or them” climate.

The right and the good have been automatically equated with the work done by the valiant Western white men in their pursuit of a better world for all: if you do not agree, you are a heartless hater of freedom.

Muslims are fair game, in the way that black people were during the height of colonialism (and still are, in some cases – simply look at the tradition of Black Pete in the Netherlands) and women are in certain masculine spaces such as men’s magazines.

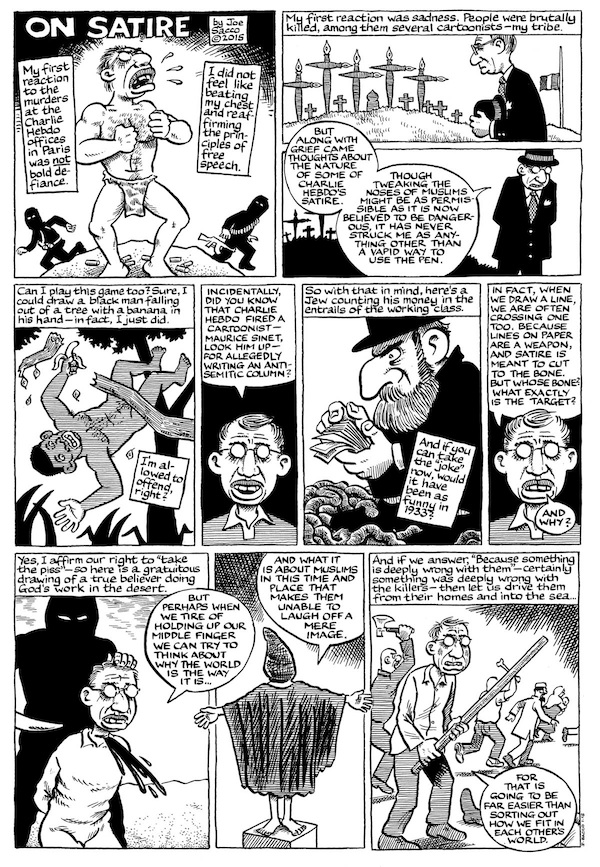

At some point it is not just about comment and criticism. It is punching down from the top with no regard for those below and what may be important to them. A cartoon by Maltese-American comic-book artist Joe Sacco sums it up beautifully when he asks whether he can play the free speech game too. He proceeds to draw a picture of a black man falling out of a tree, a Jewish man counting money in the entrails of the working class, and a believer doing “God’s work” in the desert while about to cut off a captive’s head.

Would we be OK if cartoons appeared in the New York Times about Ebola-riddled Africans? Or a series depicting crazed white men beating a black person with the caption: “White men go wild: Summer edition” as a comment on the spate of racial attacks in South Africa?

Sacco argues that satire is meant to cut to the bone, but questions: “Whose bones, and why?”

Those who say free speech means everyone is a possible target erase the inherent power play that comes with the interaction of ideas, cultures, values and rights. A white man in France has a much louder voice than a man in an Islamic nation seeing his beliefs bandied about for fun.

In 2010 Ugandan academic Mahmood Mamdani warned about bigotry in the name of satire. He said blasphemy is the questioning of a tradition from within and bigotry is an assault on the tradition from without. The defining feature of the Danish cartoon debate over the depiction of the Prophet Muhammad, he said, was that bigotry was mistaken for blasphemy. The same can be said here. Mamdani says that the past five centuries of Western domination have been marked by an increasing inability to “live with difference whilst increasingly politicising it”.

Rather than attempting to understand the context in the light of these differences and why something like this would happen in response, we put up the middle finger and react “with fear and anxiety, marked with arrogance”. We tell the world that free speech and other Western liberal ideas are king and that other notions can go kick rocks.

I am against the Paris killings, but #JeNeSuisPasCharlie because “Charlie” is at the top of a hierarchy of ideals that I, as an African woman, could quite quickly be at the bottom of. Who is to say that those ideals I hold dear will not end up at the bottom of the food chain? If they were to be scorned in the name of satire, what would I do?

Speech is not free for everyone. It can be costly for some, erasing dignity and respect for differences.

Kagure Mugo is the curator of HOLAAfrica!, and a part-time pseudo-academic and wine-bar philosopher