Energy Minister Tina Joemat-Pettersson and Rosatom director general Sergey Kirienko signed an intergovernmental agreement on nuclear energy in September last year.

On Russian technology

“The Parties shall co-operate … for the implementation of priority joint projects for construction of two new nuclear power plant units with VVER [water-water energy reactors] reactors with the total capacity of up to 2.4GW [gigawatts] at the site selected by the South African Party (either Koeberg Nuclear Power Plant [NPP] site, the Thyspunt site or the Bantamsklip site) and other nuclear power plant units of total capacity up to 7.2?GW at other specified sites in the Republic of South Africa as well as for construction of a multipurpose research reactor at the research centre located at Pelindaba.”

The specific nature of this clause appears to commit South Africa to Russian nuclear technology.

It appears that the chief state law adviser, Enver Daniels, opposed any specific references to Russian reactor technology (VVER) because it might create a legitimate Russian expectation that it would get the deal. He also expressed concerns that this clause flouted Section 217 of the Constitution that all state procurement must be “fair, equitable, transparent, competitive and cost-effective”.

Although energy department officials concurred, recommending that the areas of strategic co-operation be couched in general terms, this was ignored in the final version.

But the final version does state that the “co-operation under this agreement shall be conducted in strict accordance with the laws of each state”.

This appears to have been inserted at Daniels’s insistence.

A memorandum prepared by Daniels, seen by amaBhungane, argues that this clause is “a crucial provision, as it will ensure the Parties … do not act in conflict with their domestic law”.

On excluding other bidders

“The Competent Authorities of the Parties can, by mutual consent, involve third countries’ organisations for the implementation of particular co-operation areas under this Agreement.”

The key phrase, “by mutual consent”, in effect gives the Russians the right to block South Africa appointing anyone else to the nuclear new build project.

Considering the 20-year minimum duration of the agreement, the Russians would hold a gun to South Africa’s head if the agreement comes into effect. If South Africa does not agree to Russian terms for the initial two reactors, or chooses not to stay with the Russians for further reactors, it cannot go to other suppliers for the remaining 20 years of the agreement unless the Russians consent.

A similar clause appeared in an early draft of the agreement, as Business Day revealed in October 2013.

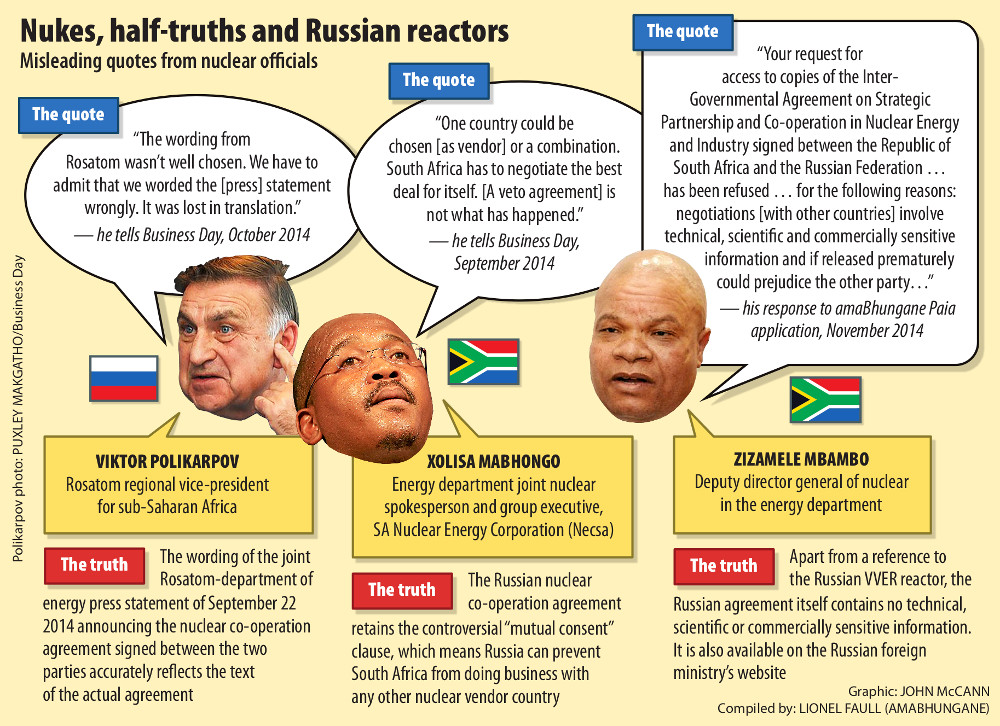

Asked whether it had been retained in the final version after the agreement was signed, one of the government’s nuclear spokespeople, Xolile Mabhongo, told Business Day it had not.

On funding

“The sources and mechanism of financing of the activities … will be determined on the basis of consultation and laid down by separate agreements between the Parties.”

Despite the seeming commitment to forge ahead with Russian technology, the agreement defers a decision about funding until further consultation has taken place.

This is problematic because South Africa commits itself to Russian technology without knowing how it will pay.

An earlier draft of the agreement is understood to have specified that South Africa would guarantee the Russians a capital return if they provided the finance up-front, but this clause was dropped at the insistence of the treasury and the department of trade and industry.

However, the signed agreement promises the Russians a host of regulatory concessions, tax breaks and other “special favourable treatment”, without factoring in the independent role of state institutions such as the electricity regulator, the national nuclear regulator, the revenue service and the treasury in determining such concessions.

On liability

“The authorised organisation of the South African Party at any time and at all stages of the construction and operation of the NPP units is solely responsible for any damage both within and outside the territory of the Republic of South Africa caused to any person and property as a result of a nuclear incident occurring at the nuclear power plant … as well as in connection with a nuclear incident during the transportation, handling or storage outside the nuclear power plant … of nuclear fuel and any contaminated materials or any part of nuclear power plant … both within and outside the territory of the Republic of South Africa.

The South African Party shall ensure that, under no circumstances shall the Russian Party or its competent authorities or authorised organisations … be liable for such damages.”

The treasury, which would have to pay for any damage, opposed this clause.

So, too, did Daniels, who referred to its “broad and almost boundless nature” as being “a particularly sticky issue” in the memorandum seen by amaBhungane.

Similar protestations about this clause from a cross-section of other government officials were ignored.

The Russians are known to have offered South Africa a “build-own-operate” model of nuclear construction financing that, if realised, could give them incentives to cut corners on safety during construction and operation.

Should anything go wrong, however, the fallout would be South Africa’s problem.

When does the Russian deal become law?

Under the Constitution, “an international agreement binds the Republic only after it has been approved by resolution in both the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces”.

The Russian deal has not yet been sent to Parliament.

However, the same section of the Constitution contains an interpretative sub-clause that, if favoured, would avoid a showdown in Parliament and thus dramatically lower the bar for the Russian agreement entering South African law.

The sub-clause says: “An international agreement of a technical, administrative or executive nature, or an agreement that does not require either ratification or accession, entered into by the national executive, binds the Republic without approval by the National Assembly and the National Council of Provinces, but must be tabled in the Assembly and the council within a reasonable time.”

As constitutional law expert David Unterhalter observes, the agreement contains “a large number of highly specific matters”. This could arguably render it an international agreement of a technical nature.

However, amaBhungane has seen documentation indicating that the state’s legal advisers in both the departments of justice and international relations believe it is a general agreement that requires the more comprehensive parliamentary approval, and not just tabling, in order to be binding. – Lionel Faull & Sam Sole

* Got a tip-off for us about this story? Click here.

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.

The M&G Centre for Investigative Journalism (amaBhungane) produced this story. All views are ours. See www.amabhungane.co.za for our stories, activities and funding sources.