To mark our continent’s freedom, when a significant number of countries gained independence in the two decades after World War II, we celebrate Africa’s liberation from colonial powers on Africa Day on May 25. But decolonisation is still a work in progress. Occidentalisation is firmly entrenched in the psyche of Africans in terms of socialisation, identity and the way we are represented locally and globally.

With a population of one billion, there are only about 280 000 internet users on the continent, according to Internet World Stats, with Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya three of the top five countries in terms of internet connectivity.

But who is narrating our story and creating and mapping Africa’s digital footprint?

In the creative sphere, across Africa, the narrative is already being digitally rewritten and archived by artists who have been troubled by hackneyed and problematic representations of the continent and the dangers of globalisation.

“What I attempt to do through my work and in my life is to unlearn all the nonsense I’ve been fed with growing up in the West,” says 26-year-old video artist Tabita Rezaire, who grew up in Paris but has been living in Johannesburg for the past 10 months. “I am trying to free myself (and potentially others in the process) from the spiritual, social and political oppressions of the colonial matrix of power. It is about unlinking with Eurocentrism and the pervasive hierarchy between races, genders, cultures and systems of knowledge.”

Rezaire is one of 19 artists who are showcasing their works as part of an ambitious and potentially game-changing exhibition, Post African Futures, curated by Tegan Bristow, an interactive digital media artist and head of interactive media in the digital arts division of the University of the Witwatersrand’s school of arts.

Bristow says the exhibition is an extension of her doctoral research through the United Kingdom’s University of Plymouth and came about because she was concerned about how we are “teaching European digital media and digital arts practice to students who aren’t even looking at digital media and digital art in that way at all. It’s a little destructive.

“There’s all kinds of different social political agendas around global technologies, which I think everybody in South Africa is aware of since we are specifically represented in global media in a very closed-minded way.”

Emeka Ogboh’s video work.

She embarked on a survey to see what artists in Nairobi, Johannesburg and Lagos are doing and how they’re thinking about digital media. “I think African internet practice is really quite a heavy response to globalised internet practice in a humorous yet critical way. The weird deconstruction of things like Western memes and the odd sort of digital look is really a response to global media.

“I also realised that, in terms of digital media, one of the problems is that Africa is seen as one thing. So any book that I found, any journalistic article around mobile media development, tried to contain Africa as one identity.”

The focus on the notion of technology and African culture came about after reading one of the only papers (published in the 1990s) she found on the subject in Kenya, written by a Kenyan scientist.

“He was saying that you can’t look at science and technology in … Kenya in the same way you look at it in South Africa,” says Bristow, “because there are all sorts of sociopolitical and socioeconomic issues that affect the way people understand it and also how people transfer knowledge amongst each other – so the systems of knowledge transfer is completely different. It’s more social [in Kenya] and has evolved in a different way.”

When I ask Rezaire about the representation of black people in media and the arts and what she would like to see change, she says: “I would like mainstream media to stop publishing lies. I would like all media to stop perpetuating dehumanising stereotypes of black people. I would like the internet to not fetishise, eroticise, instrumentalise, criminalise or exoticise black bodies. I would like Western-saviour syndrome to end. I would like white fragility to be overcome. I would like cyber-racism to stop. I would like social media backlashes to stop. I would like to feel safe on the internet and to feel proud.

“I want all the amazing black online initiatives and all the young kids contributing to empowering narratives to keep doing what they are doing. I want every black person on this planet to feel like a queen by scrolling and clicking on the internet.”

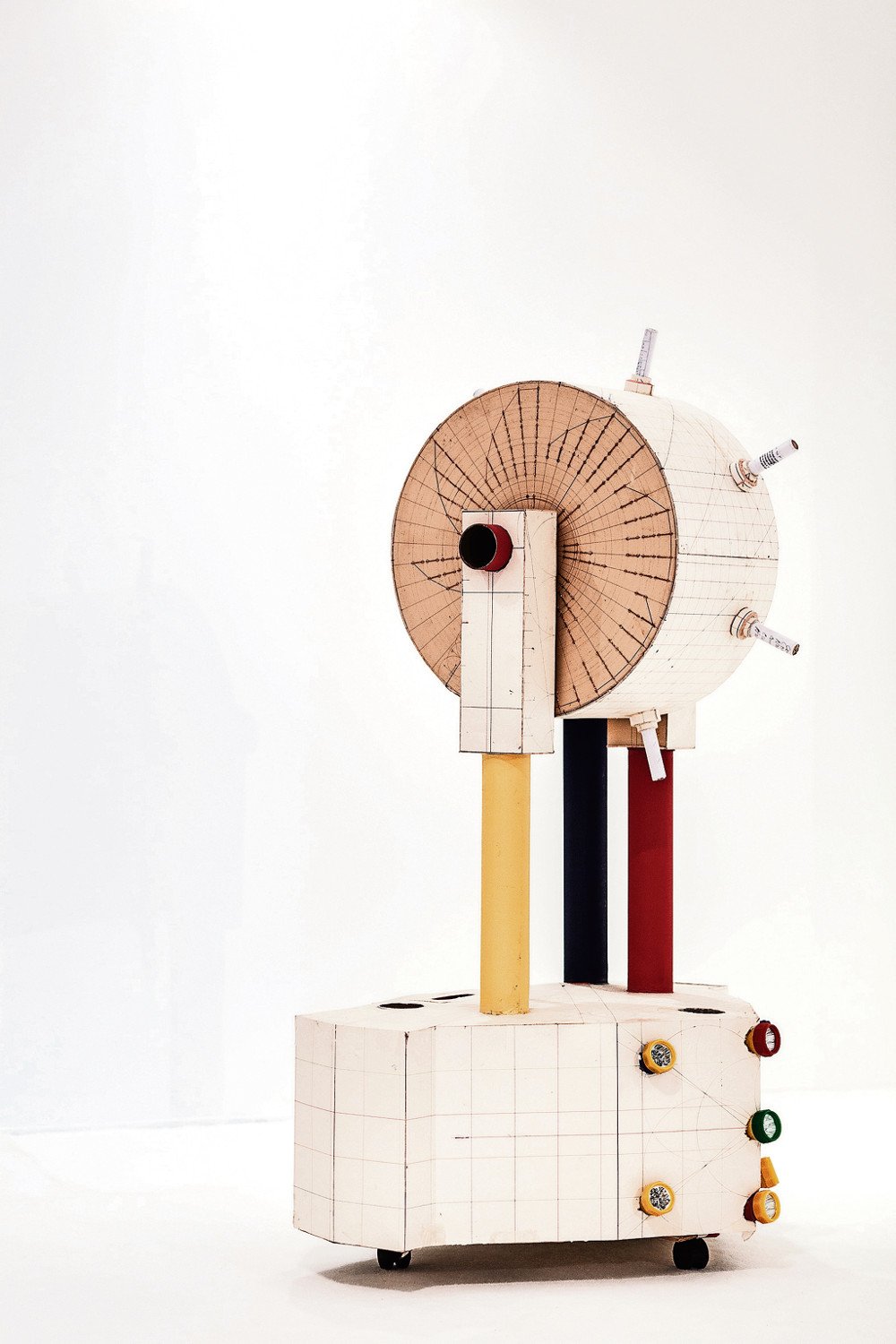

Jean Katambayi Mukendi’s Paper Computer.

Rezaire is presenting Sorry for Real, a virtual apology on behalf of the Western world. “The work questions the apology-forgiveness narrative and the role the apology might have today as a Western tool of control and oppression. It somehow mirrors my feelings about technology.”

Stills from Rezaire’s Sorry For Real (2015) show a digital image of a ringing cellphone; the Western world is calling and the viewer has the option of declining or answering the call. The words “the Governor and the Administrator of Entire Universe” appear as the caller’s profile image and green text bubbles around the phone bear statements like “OMG, they gonna send a drone on you via Bluetooth” and “Yo bitch, are you gonna answer this?” The simplicity of the image succinctly drives the message home and relays Rezaire’s view of globalisation and Western domination.

Rezaire will also be launching a new tech agency called Ntu founded by Bogosi Sekhukhuni, Nolan Oswald Dennis and herself, and presenting NervousConditioner.Life.001.Ntu, an installation of a server they created that will host an online forum in which people of colour can safely discuss, share and organise.

Security, freedom and the threat of globalisation are big concerns for artists working in Africa’s digital space – most notably for a country such as Kenya, dubbed the “Silicon Savannah”.

The country is still suffering from the restrictive and repressive rule of former president Daniel Arap Moi. In the postelection violence that broke out in 2007, a few Nairobi coders created Ushahidi (meaning testimony in Swahili) – a data-mapping platform that collated and reported reports of violence through text messages, emails and social media such as Facebook as a way of keeping people informed.

In 2011, Time magazine reported that Ushahidi had become the world’s default platform for mapping crises, disasters and political upheaval – and that it had been used 14 000 times in 128 countries to map everything from the 2010 earthquake in Haiti to the 2011 Japanese tsunami and the Arab Spring.

Bristow says Ushahidi led to the building of the Nairobi iHub, which is one of the most famous tech hubs on the continent because it was one of the first and one of the most successful. It has spawned more start-ups than any other in Africa.

Haythem Zakaria’s Anamnesis.

Bristow says: “Kenya is overwhelmed [by a vulture economy] because everything they make is being stolen and they’re working quite hard to keep it [their innovation] Kenyan. When you look at aesthetic practice in Nairobi it’s driven by narrative – this is the country that spawned some of the best writers on the continent.

“They also don’t have a strong visual contemporary art scene so narrative and storytelling and filmmaking are very much more their contemporary critical space. You’re seeing a lot of short films, music videos, [and] arts practice which is about looking at digital media, social media, mobile media as a kind of activist thing. Social activism is very much a part of their critical and social discourse.

“Africa has these two cities [Nairobi and Johannesburg], which are so different because their cultures of technology are so different. Cultures of technology are key to understanding our own position – for me, for teaching that’s important so our students, too, can understand where they are and not taking on this one global power understanding of media, predominately from the West, and that tries to negate everything that doesn’t subscribe to Western thinking or practices.”

With time and resources being a factor, Bristow excluded Lagos from her research for now but hopes to be able to pick it up at a later stage, using the snowballing technique of asking experts in the field to refer her to two others she should speak to who are influential in that specific space.

“I quickly got a dynamic-looking map of who’s associated with each other in the two cities and how they understand themselves within the critical and tech engagement. I started with a technology person and then a creative person, and media sort of fit in the middle – especially in Kenya. Because it’s narrative driven, it often brings the tech and the creative together.”

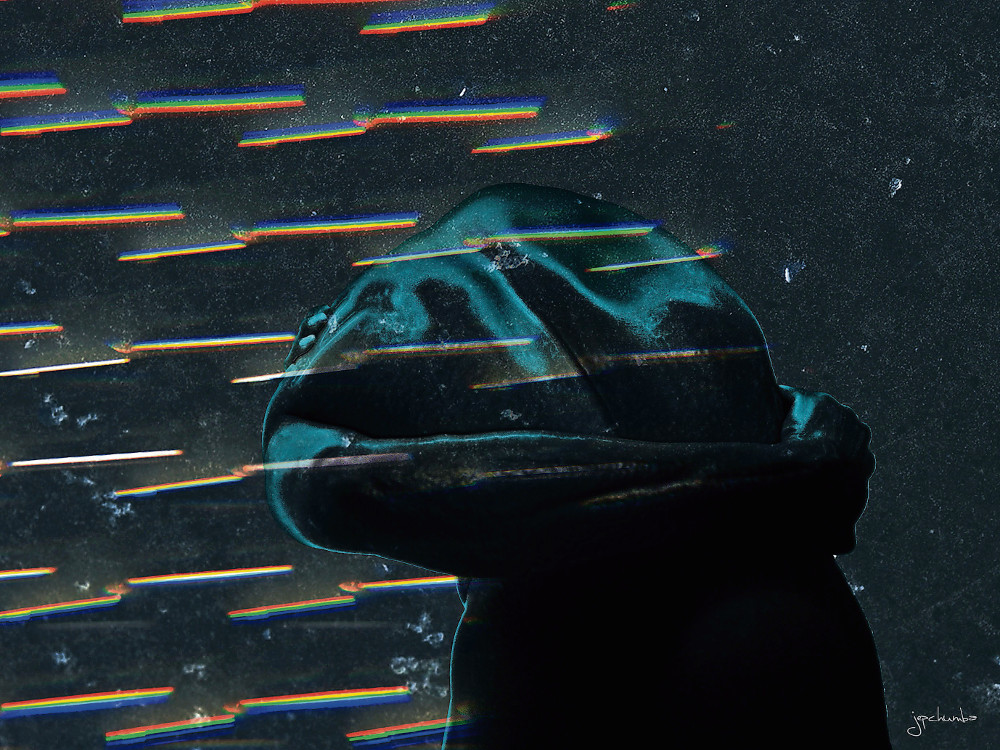

Of digital artist Jepchumba, whom Bristow met at an African digital art conference in Germany, she says: “Jepchumba started her [web] platform, African Digital Art, as a way of talking about digital art way before sites like Okay Africa and Contemporary And were around and she’s really very concerned about how discourses happen around digital art and how people get info and share it.

Jepchumba’s Dontshoot II.

“Jepchumba was reluctant to exhibit because she believes African art is a little like an airport – a stopover to somewhere – and because it’s so trendy right now there’s no real discourse about what’s really actually happening or who those artists really are. It’s just really colourful and nice.”

So she is compiling a podcast series for the exhibition and interviewing all the artists about the notion of post-African futures, their work and trying to say what they feel about it.

The selected artists are presenting both old and new work as well as fresh collaborations and new companies such as Ntu.

There will also be a performance involving Just a Band, Okmalumkoolkat’s Smiso Zwane and the Brother Moves On. It’s a meeting of creative, hypothetical imaginings where the alter egos or fictional characters of the Brother collective (Mr Gold, who’s already dead but gets brought out of the coffin every now and again) and Kenyan funk-house-disco group Just a Band’s Makmende character (a fictional blaxploitation-style superhero) will come together in a performance, called The Afterlife with Okmalumkoolkat.

“There’s a mythology around how to tell stories in that space. Mr Gold is very much about power structures, as is Makmende, so the idea is to get them together in a conversation,” says Bristow.

The art exhibition is evolving and taking its own shape as Bristow curates it. Much like the digital framework, connections are made, conversations are started, creativity is sparked and ideas form.

Says Bristow: “Through the PhD and research process there’s been a lot of evolutional thinking so the exhibition is quite heavily about definition – like trying to make claim to certain kinds of thinking of certain kinds of criticality that exist within those practices because I think people don’t necessarily see the critical engagement with digital and tech and global.

“It’s about bringing that to the surface, making it clear and apparent. But it’s also about working with and bringing to the forefront very talented artists working in this field, who are often sidelined because they work in performance or work on the internet. It’s really about talking about cultural engagements through digital in a very contemporary and exciting way as part of culture and discourse.

“This will go into my teaching and this will inform how people think about themselves within the scheme of creative practice and cultural engagement.”

The Post African Futures exhibition, which opened on May 21, features talks, screenings and performances over four weeks by artists Bristow has been writing about for a long time including Rezaire, the Cuss Group (a Johannesburg-based video artists group founded by Jamal Nxdelana and Zamani Xolo), Sam Hopkins (Kenya), Imagining Lagos Collective (Nigeria), Jepchumba (Kenya), Just a Band (Kenya), Wanuri Kahiu (Kenya), Kapwani Kiwanga (United Kingdom), Jean Katambayi Mukendi (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Muchiri Njenga (Kenya), Emeka Ogboh (Nigeria), Haythem Zakaria (Tunisia) and Ntu, Okmalumkoolkat, Brooklyn J Phakati, Lebogang Rasethaba and Nthato Mokgata, Pamela Phatsimo Sunstrum and Thenjiwe Nkosi, and Dineo Seshee Bopape, all from South Africa.

Post African Futures runs until June 20 at the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg. Visit futurelabafrica.org for more information