Youth

‘I’m 25; I’m unemployed,” says tourism graduate Lehlohonolo Diphare.

He lives with his grandparents and brother in a four-roomed, matchbox-style, apartheid-era house in Zone 11, Sebokeng, and explains the implications: “I can’t have children. I can’t get married. How will I take care of them? I feel like my life is over.”

The township of Sebokeng is part of the once blooming industrial heartland of the Vaal Triangle in the south of Gauteng. The local steel industry, which made this one of the country’s economically thriving areas, is on the verge of collapse with plants closing and major companies bleeding jobs.

Diphare graduated with a certificate in tourism in 2013 from the Sedibeng College for Further Education and Training. Unable to find a job in his field of study, he first worked as a security guard for a few months. Later he became a labourer for the government’s expanded public works programme, fixing the R82 road that connects Vereeniging to Johannesburg. But that job’s done.

Diphare now sits at home day in and day out. He has simply given up on finding a job. His house stands as naked and unpainted as when it was built in the early 1980s. It has four tiny rooms with a toilet. There’s a tap outside.

Graduation photos

Behind the house is a rondavel with a thatched roof. “My grandmother is a sangoma and she treats her patients in this house,” he says and pushes the front door open. There are two photographs placed on the dining room wall: one of Diphare and the other of his brother, both smiling brightly in their graduation robes. His grandmother sits in the small room watching TV while her traditional medicine cooks on the stove.

We go back and sit outside.

After he finished his matric in 2007, Diphare worked for two years to save money to pay for his tertiary education. He moved in with his mother, a domestic worker who lives in a shack in Muvhango, a squatter camp close to the nearby industrial town of Vanderbijlpark.

“Those were hard days. We would go without food but I knew I had to persevere. I would walk kilometres to college and back every day. I only had one pair of shoes for those three years. I thought everything would be better after I graduated.”

Diphare studied tourism because he thought it would afford him the opportunity to see the world. He has never left Gauteng province.

High unemployment

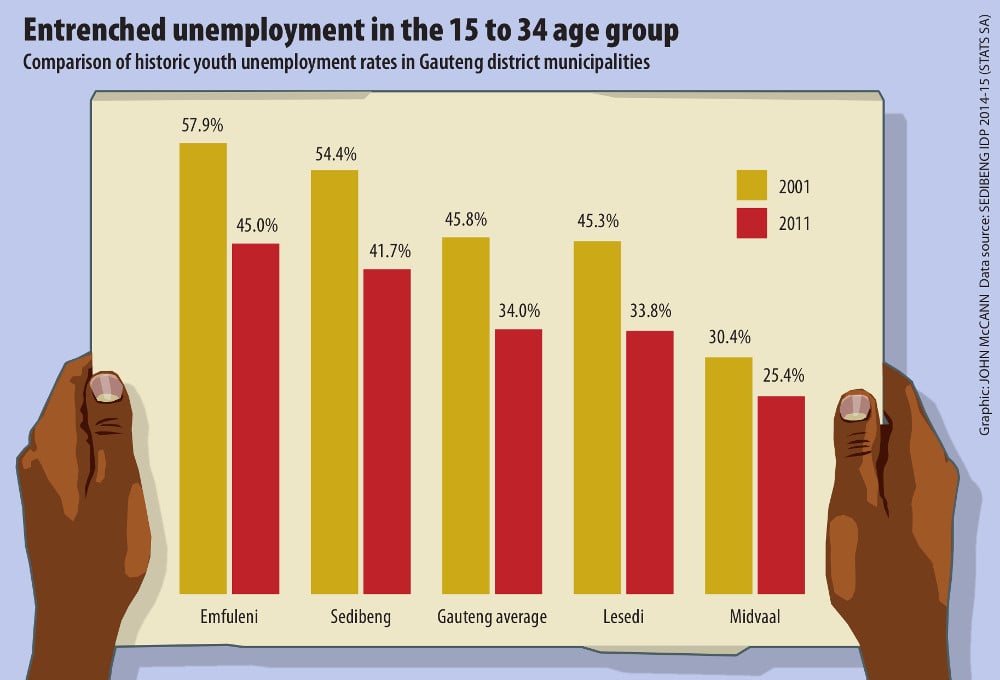

Sebokeng is part of the Sedibeng district. Unemployment was at 43.9% in 2001 and 31.91% in 2012, according to the Sedibeng Integrated Development Plan for 2014-2015. It is even worse for people between the age of 15 and 34: 54.40% in 2001 and 41.70% in 2011.

The Gauteng socioeconomic review and outlook for 2014 also shows that the Sedibeng district had the highest percentage of people living in poverty and who are unemployed in the province. The report, compiled by the Gauteng finance department, showed that the unemployment rate among black people has increased in all three of the district’s municipalities, Emfuleni, Midvaal and Lesedi.

Some unemployed young people in the Vaal Triangle are starting up small businesses, such as selling fruit. (Photos: Oupa Nkosi, M&G)

The largest increase was in Emfuleni where unemployment rose from 57.1% in 2003 to 65.1% in 2012. The unemployment rate among white people decreased in all three municipalities. The total unemployment rate in Emfuleni increased from 51% in 2003 to 57.2% in 2012, compared with Midvaal’s 11% in 2012 and Lesedi’s 24.8%.

It is Monday morning, 9:30. Diphare has joined four of his friends on the lawn of another house like his, also in Zone 11.

The five are all in their early to mid-20s and unemployed. Some didn’t finish school.

“I got kicked out of school in grade 10 because I stabbed a classmate with a pair of scissors,” says one and the others laugh.

Two bottles of beer are passed between them.

“No sister, we are not all the same,” one of the friends says to me. “I am a retail marketing student at VUT [Vaal University of Technology], third year. I took the morning off but I have organised my notes. I’m going back to school later today.”

Meeting spot

This house is their meeting spot. They pooled their money, bought two bottles of dishwashing liquid, a few rags and a second-hand vacuum cleaner and started a car-washing service. Weekdays are quiet. Not one car comes to get washed on the Monday or the Tuesday we spent with the guys.

This is where Diphare says he makes some money. He then uses the money to buy cigarettes and eggs, which he sells at the train station on weekends.

The car wash business opened by an unemployed youth in the Vaal Triangle.

The guys spend the better part of any given day here, drinking beer or cooldrink, and eating skhambane – a quarter loaf of bread filled with slap chips, atchar, polony and any other extras you may want to add. By 11am some are slurring. A few hours later they struggle to stand up.

“There is no work, my sister,” one of them explains. “We just sit here. We want to work but every time we apply either there is no response or we are told to write some tests, then nothing.”

Nhlanhla Mathe (22) joins the group. He is also a student at Sedibeng College and his majors are communications and public relations. “I was supposed to finish in November last year but for me to get my diploma I need to intern at a communications or PR firm as part of the qualification,” he says. “I have not been able to get an internship for a year.”

Sad tale

Mathe has dreadlocks tucked under his stylish hat. He smiles easily, but his tale is sad. He says he has been stuck in the township and now hangs out at the car wash to pass his days. Mathe is already an old hand at applying for jobs. “Come and check my CV at home,” he insists.

Mathe lives with his grandmother but his house is bigger. He thinks the reason he hasn’t been offered an internship is there could be something wrong with his CV.

“I know there are jobs but I don’t have internet,” he says. “I don’t know how to write a proper CV and I can’t ask my gran because she doesn’t know. I don’t have money to go to town to use the library so I am stuck.”

He says he sometimes uses his smartphone to search for job opportunities but that has proven difficult.

Mathe says he worries he will end up like his friends who have tertiary qualifications but have fallen into the trap of “nothingness”.

“There is nothing to do here so we wake up, go to the car wash,” says Mathe. “Some drink.”

“And you?” I ask him. He shrugs his shoulders and looks past me. “I come back home and do nothing.”