'Black President' is a film about artist Kudzanai Chiurai

There is a moment in Black President, the new film about Zimbabwean-born visual artist Kudzanai Chiurai, when he is asked how he rationalises people’s opinions of his work. A seemingly dazed and unusually inarticulate Chiurai gives a half-hearted answer about how he does not care what people think of his art.

There is a glare of indifference in his eyes and you get the feeling that he would rather be somewhere else rather than doing this, here and now. It’s difficult not to read too much into this moment, considering the events that followed as Kudzi, as he is affectionately known, abandoned the life he had built in Johannesburg to return to his native Harare.

Mpumi Mcata is a familiar face in South African creative circles and, depending on who you ask, he is one of the finest guitarists to come of age in Thabo Mbeki’s South Africa. The bushy-bearded soul man is one of the minds behind seminal Bantu-rock outfit BLK JKS and one-third of ethereal rock outfit Motel Mari.

Black President, however, marks Mcata’s maiden voyage into the world of cinema, a project that has been five years in the making.

“I had wanted to make a film but had no plans to tell this particular story. By the time I got involved with the project, two other directors had been hired and fired from the film,” says Mcata.

“One day I was in the lift and was chatting to the producer of the film about my perceptions of Kudzi and his work, and a few days later I got offered to direct the film. I didn’t agree immediately until Kudzi later asked me to do it – and then I agreed.”

Finding new meaning

The film, which premiered in February at the Berlin International Film Festival and had its African debut at the recent Durban International Film Festival, is showing at the Bioscope in Johannesburg’s Maboneng precinct. There are also plans to screen it at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe later in the year.

Mcata points out that he enjoys seeing how Black President takes on new meaning every time it is screened, based on that particular audience’s background.

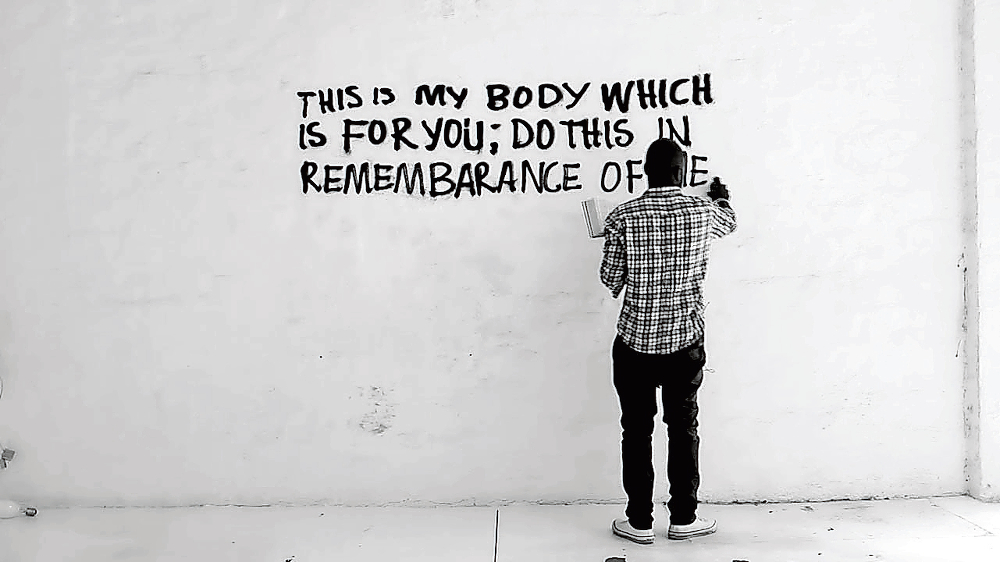

Black President Remembrance (End Street Productions)

“It was great to see and hear from the Berlin audience; they loved the film and took it in. I’m also happy with the way the film was [received] in Durban. The questions and context were different, as we are now on African territory. It changes every time you watch it and as we step closer to the film’s spiritual home in Zimbabwe. I feel like the film is edging closer to finding its feet and life.”

Asked what the film’s subject thinks of the final work, he lets out a deep sigh before confessing that Chiurai has not seen it – and is not likely to any time soon. “Kudzi hasn’t seen the film and Kudzi does not want to see the film. That’s how it is right now for his process, but he respects the work,” says Mcata.

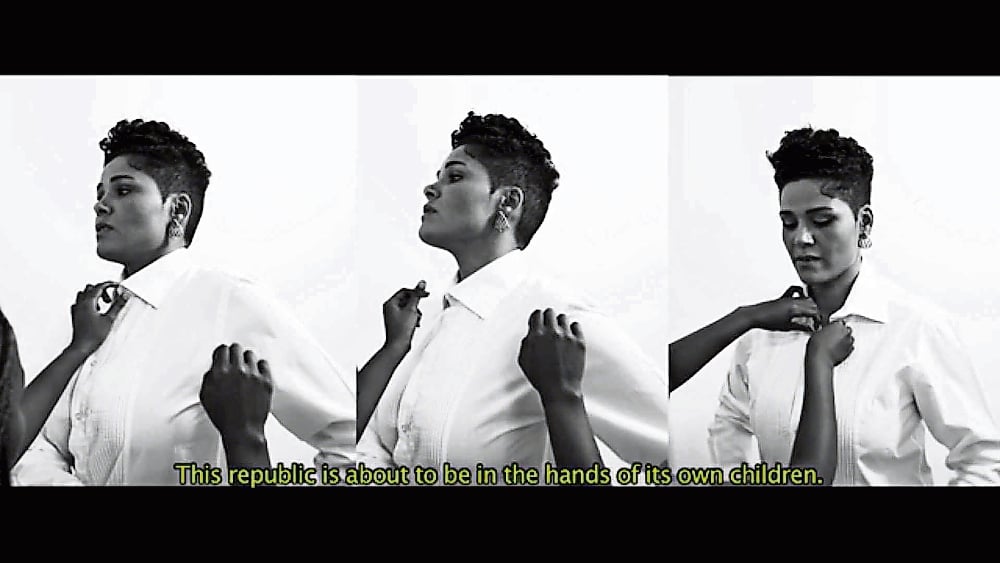

One of the things that make viewing Black President exciting is how seamlessly it merges reality and fiction. The characters in Chiurai’s work, particularly those from his State of the Nation exhibit, appear throughout the film, delivering speeches, rousing monologues or statements of intent.

These appearances are nestled among scenes of Kudzi at work, Kudzi at home and Kudzi in various states of being in the contemporary visual arts scene of downtown Jozi. The film, intentionally or not, draws parallels between those imagined lands and our own reality.

A portrait of a moment

“People have watched the film and could not tell the difference between what is real and what is fiction, and this is part of it: that there is magic in the everyday and sometimes when we don’t acknowledge that, we shy away from certain responsibilities,” says Mcata.

Black President is also littered with cameo appearances, from Okmalumkoolkat, Zandi Tisani and Zaki Ibrahim to Thandiswa Mazwai. Speaking about how he got so many accomplished creative talents to rally around a project with virtually no budget, Mcata is reluctant to take any credit.

“In this film, a portrait of a moment, the people are brought together by Kudzi himself. So, to document his life and his space and time as it was, you couldn’t cut those people out of it,” he says.

Black President Of Children (End Street Productions)

It’s no secret that Chiurai and Mcata had been friends for some time before the making of Black President. How did he afford himself the essential distance to view Kudzi’s life and work and treat it with the necessary scepticism that could lead to a film as charged as the one he has made? Mcata points out that Black President is not a film that exists despite his friendship with Chiurai. It exists because of it.

“This film is peer to peer and in some ways, that was the easiest part – because I felt like I am not in awe of him in some unnatural way,” says Mcata. He adds: “My friendship with Kudzi also meant that I was not as interested in the biographical elements of his life, so Black President became more and more a film about his ideas as opposed to events in his life.”

One of the most intriguing things about the film is that it showcases the humorous side of Chiurai and his work. Despite the heavy political themes and a recurring questioning of power and its meanings on the African continent, Black President draws our attention to the fact that although the work is earnest, it is not humourless. It is teeming with irony.

Loose ends of a narrative

Black President also marks the opening of a new lane in the vernacular of South African cinema. It is a film that is made in the spirit of openness and lacks the traditional beginning, middle and end that is associated with most films.

It’s postmodern in its nonlinear narrative structure but also in its mangling and constant relinquishing of identity; there is no exposition about Kudzi or his origin story.

It operates from an assumption that if you are watching Black President, you already know who Kudzanai Chiurai is and you don’t need to be bored with the details – and if you don’t know who he is, you can get absorbed in the work anyway. Black President can best be described as improvisational. It is speculative cinema at its height.

Anyone familiar with the story of Chiurai, and how he left South Africa after a stay of more than 10 years and returned to Zimbabwe, has a vested interest in trying to understand what really happened. But in this regard, Black President is disappointing. It intentionally does not tie up the loose ends of the narrative.

The film reveals that there was no momentous reason for Chiurai’s return home. Here, Mcata is subverting our expectations and mocking our desire for a bigger mythology around the artist.

“There were a lot of rumours about Kudzi’s situation in South Africa and back at home, [going] back and forth. And nobody really asked the questions as to what was actually going on. It’s like we all played into this myth because we wanted it to be a certain way. We wanted this African artist trapped in South Africa, which it may or may not have been,” says Mcata.

Black President will be screened at the Bioscope Independent Cinema, 286 Fox Street, Johannesburg, on August 23, 24 and 29, and September??13. Visit thebioscope.co.za