The ANC has denied that the handing out of houses this week was an election stunt.

Beds are passed down from generation to generation at the Thokoza Women’s Hostel in Durban. Young women sleep on the floor, waiting their turn to inherit a bed. Women go grey, and even on pension, while living in the hostel.

It’s a home for thousands of working-class women who have moved to the city to get jobs. Some find a job and a new family, and never return to their families, who often live in rural areas.

In 2011, Durban photographer Angela Buckland turned her focus on the hostel in an attempt to “articulate displacement, a home away from home, and to acknowledge the lives of hostel dwellers”.

The hostel, which was built in 1925 to house black working women, was the first of its kind in South Africa.

Buckland’s photographic installation, Block A, Thokoza Women’s Hostel, features 699 small prints and personal information – names, occupation and hometown – of the residents. The exhibition has toured South Africa and Italy, and its final stop is at the Pretoria Art Museum.

Hostels during apartheid were inhumane. People of colour were stacked up in rooms like sardines and slept on concrete bunk beds. Block A documents the lives lived in overcrowded hostels.

Post-democracy, single sex hostels are a reminder of South Africa’s dark and painful past. You can still find them in different parts of the country. Minister of Human Settlements Lindiwe Sisulu has spoken out strongly about their continued existence and wants them abolished.

But for many men and women, the single sex hostels are all they can afford. In 2015, the Thokoza Women’s Hostel made headlines after a group of its residents opposed the rule that prevents them from having their children with them. Some have smuggled their children in, but, with about three women already sharing a room, it’s difficult to accommodate more bodies in an already cramped space.

When Buckland started the series, there were 162 rooms with 600 residents in the old section of the hostel.

“With the equivalent of over 5 000 residents per hectare, it is the most densely inhabited residential site in Durban.

“It is overcrowded, as women seek independence and a safe haven from a male-dominated society,” Buckland said. “There is high demand for a bed space in the hostel.”

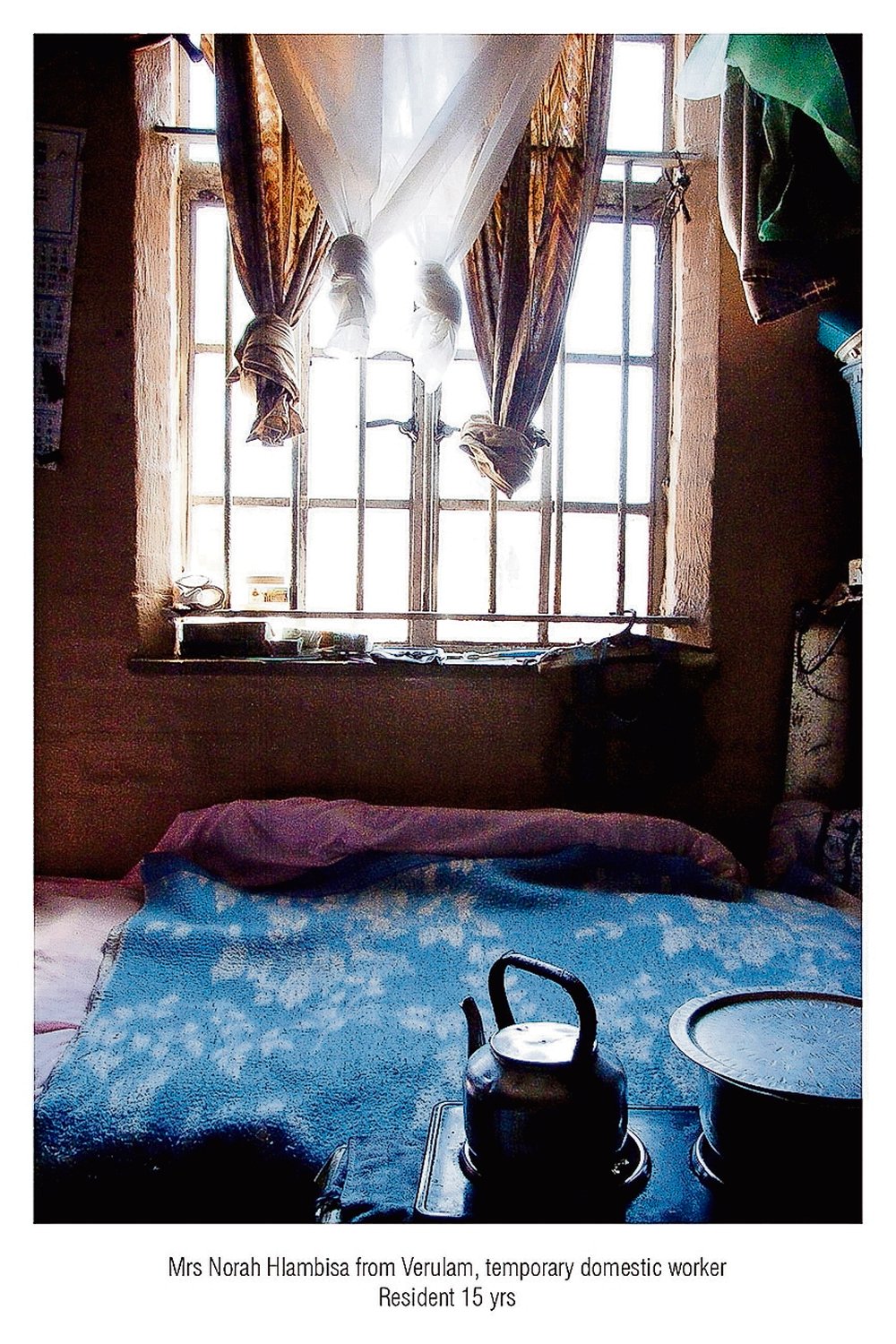

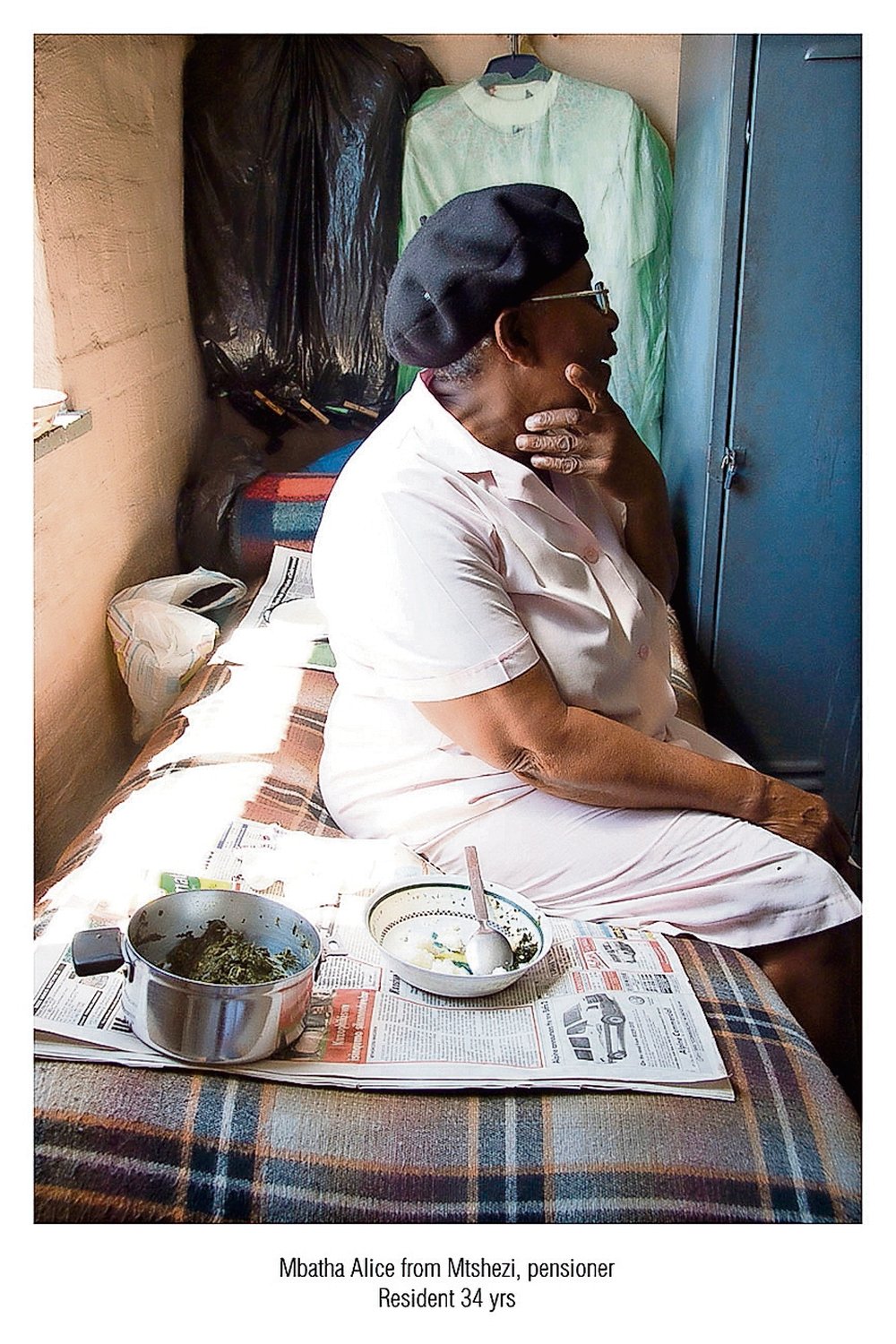

The bed became a motif for Block A. She introduced the residents with photographs of their beds and living space. You don’t necessarily see their faces, but their bedrooms give an indication of what they call home. Photos of doors also recur throughout the installation. They introduce the rooms, sometimes going from the beds to portraits of the women.

In one photograph, fabric is lying all around Fikelaphi Bhengu’s table. She is hard at work, sewing what looks like colourful aprons. She works as a dressmaker. Her greying black hair is braided and she is wearing a wedding ring.

In another room, a kettle and a pot are on a hot plate, near Norah Hlambisa’s single bed. A blue blanket, the mattress and pink sheets peep out. The bottom of her curtains, which hang above her bed, are tied up in knots to allow sunlight into the dark room.

She is from Verulam, 27km north of Durban, and is a domestic worker. She has been living in the hostel for 15 years.

Manxumalo, from Johannesburg, sits on her bed with a blanket covering her legs. She has a bowl of beads in one hand and a needle and thread in the other. She is a beader. On her lap is a Zulu beaded belt she is completing. Her clothes hang over her crowded bed and her belongings, bags and hair products are stacked against the wall. She has been living in the hostel for 35 years.

Buckland has an interest in living spaces. Block A was developed after her 2002 Block A, Jacobs Men’s Hostel photo exhibition, which featured beds in Durban’s oldest men’s hostel. That series consisted of 542 prints.

Buckland says the Jacobs hostel was extreme in its design and inhumane living conditions. “Men lived in dormitories, usually 19 single beds in a room. A lot of these bed holders were shift workers. Sometimes a single bed accommodated three shift workers at different times and they shared the rental. There was an extreme lack of privacy in the Jacobs hostel.

“But the Thokoza Women’s Hostel, on the other hand, has small rooms, which give privacy and a sense of a home; and often family members share a room, or women of the same age group with similar alliances share a room,” she said.

The residents are of all ages, and include pensioners, domestic workers and street vendors. It’s like a retirement home and a young ladies dorm all in one. They pay a monthly fee of between R105 and R125.

“The photo series features numerous women who [were] pensioners at the time, who had been staying in the hostel for 30 to 40 years.

“The story of the elderly women in the hostel is fragile. While I was making the artwork, their stories unveiled an extraordinary tapestry of detail.

“My understanding was that, due to the length of elderly residents’ stay at the hostel, the hostel environment had become their home away from home, and due to the distance from their homes and less contact, obviously family relationships faded – the tragedy, legacy and consequence of apartheid. Mothers, wives and sisters became strangers to their own families,” she said.

Since mining started in the 1800s, single-sex hostels were at the root of family disintegration.

Hlengiwe Makhathini, a resident at the hostel since 2014, says most of the elderly women in the hostel don’t want to live in old age homes.

Her wish is for the municipality to transform the hostels into family units. “We would like to live with our families because often kids are being mistreated back at home while the mothers are here in the city.”

She says women no longer sleep on the floor in passages in the hostel but overcrowding is still a big issue. “I think there are more than 5 000 people living here. There are supposed to be 900 beds but two or three people share a bed.

Block A, Thokoza Women’s Hostel opened on Wednesday this week at the Pretoria Art Museum