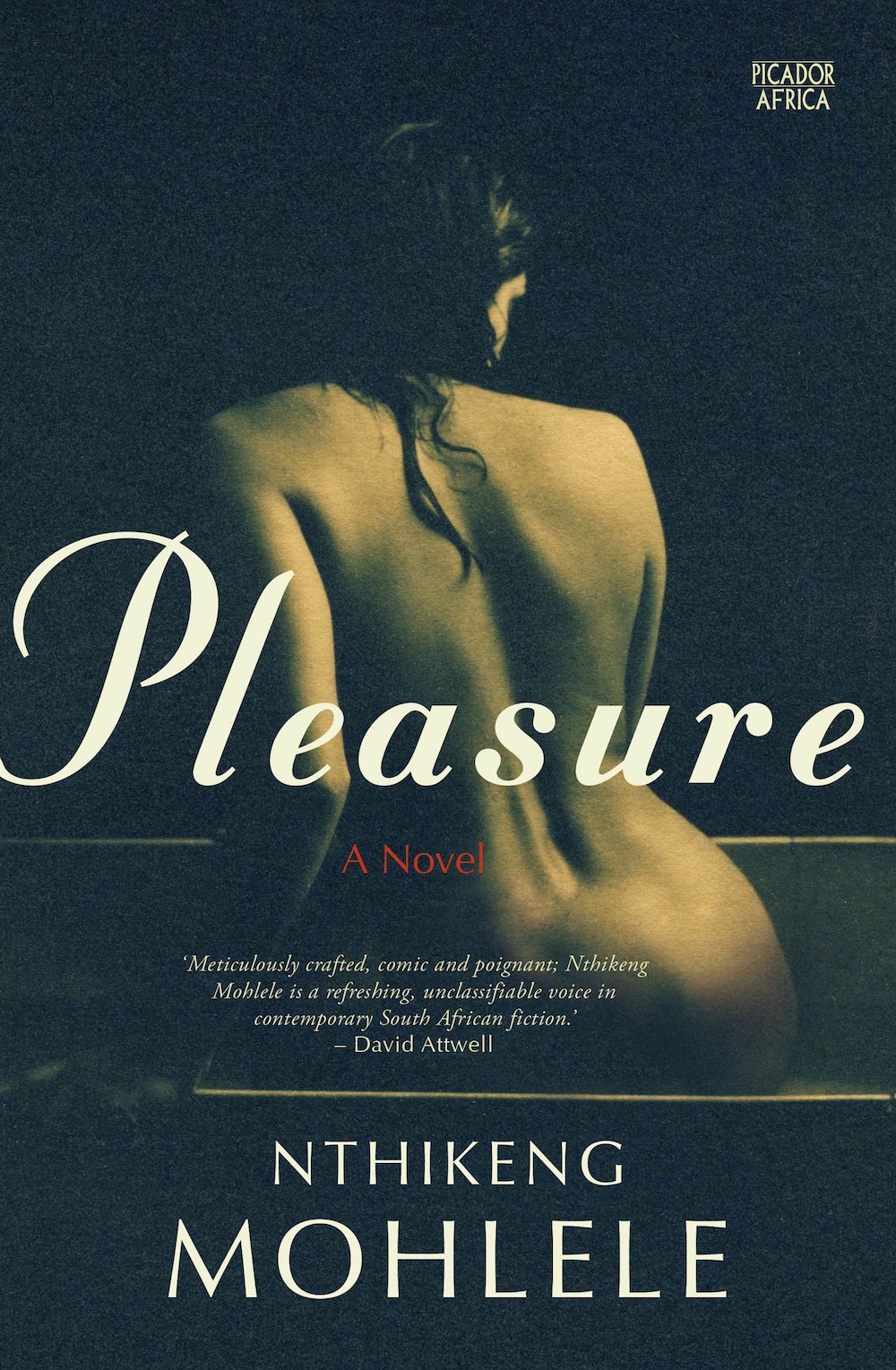

PLEASURE (Picador Africa)

Nthikeng Mohlele

Nthikeng Mohlele’s latest novel is an ambitious exploration of pleasure beyond its superficial interpretations. Set in Cape Town and, through an extended dream, World War II Europe, Mohlele traverses terrains, race and time in his examination to produce a book that is, as he says, steeped in history while not being constrained by it.

The lead protagonist is writer and teacher Milton Mohlele, a man of modest fame with a roving eye and indulgent sense of appreciation for the sometimes physical and ephem-eral nature of pleasure. He prides himself on his immersive attention to detail and in the trysts these lingering observations later yield. His is a world enraptured by the sensual and the shifting attentions of his cast of lovers: Abella, Alexis, Masechaba and former wife Orapeleng. But beyond the furtively attainable and desires bubbling in silence, just beyond reach, Milton is preoccupied with sensory stimulation.

“I observe the wing patterns on murdered mosquitoes, raindrops on patio tiles, the wheezing sounds made by babies sucking on emptying bottles.” Milton’s life is also unravelling for no apparent reason. “Trouble loves me. That’s for sure.

“My life has been composed of side-stepping all sorts of troubles, ones I was born with (temperament, idealism) and those I found in the universe. It is as if they seek me out, can smell me, like a bear sniffs victims at great distances, then follows a trail, claws at the ready, to do battle.”

Through Milton’s dreams, we meet a character named Giovanni Gomez, an American soldier captured and improbably spared by the Third Reich’s SS unit. Gomez is fated to a life of house arrest, polishing his foes’ army boots, being fattened on sausages while dreaming of his wife Elisabeth’s ample thighs.

But a most curious intruder soon becomes a part of his routine, a silent cleaner and bather named Marie Amsel, who is also in the begrudging service of the SS.

Gomez’s flummoxed reaction to these silent, nocturnal baths — probably devised to drive him to the brink of madness with arousal he cannot act upon — make for some of the more beautifully sustained passages in the book. Milton’s ruminations on restraint, born out of a strong suspicion that to touch Marie Amsel would lead to a certain death, finds the protagonist revelling in the very nature of unrequited desire. Mohlele describes Giovanni’s crippling inner stirrings with a brutal sensitivity. But for all of Milton’s insights, his is a life of squandered pleasure.

Besides the literary crisis of being his writer father’s intellectual inferior, as he writes a book on pleasure Milton is actually a man with a very static and uninteresting love life. Most of his erotic rendezvous take place in his head, with lovers that have, at one time or another, deserted him. Milton is an ageing womaniser. This frustration with his slippery allure, of being desired by a former wife whose flame for her has been extinguished in him, of constantly revisiting moments he can only touch with the imperfect lens of memory, gives the story its impetus.

Mohlele’s mastery of prose means that at all times he is able to transfer’s Milton’s, or even Giovanni’s tensions and frustrations on to his reader with the greatest of guile.

Moreover, Mohlele asks us to consider even acts of sadism as those driven by perhaps a perverse sense of pleasure. It is this boldness that gives this book an assured delicateness.

At some point during Giovanni’s imprisonment, Jews are being gassed in concentration camps. Giovanni, sheltered from the public save for Marie’s visits and the odd checkup, has an overwhelming sense of the gravity of events signified by the insistent falling of heavy ash from the sky. The ash taints everything that it touches and falls into the tea of the SS commandant.

As a story, so much happens in the ultimately ill-fated Milton’s head that only some of Pleasure’s characters are rounded. But even in his skimping, Mohlele has an inventiveness and a confidence in his execution.

As Milton’s life hurtles on at break-neck speed, he still has a few more lessons to take in on what is seemingly a life-long exploration: “The truest and greatest pleasures, there-fore, exist not between people and things, but lurk in the tiniest fragments of a moment, the unlikeliest encounters and the most improbable outcomes, entirely unrelated scenarios fusing into concoctions of outcomes.”