In his evidence, Ferreira said there was a strong prima facie case against Mdluli and he believed they had all the evidence they needed to secure a conviction.(Cornel van Heerdan/Gallo)

LAW

Everything I did before Mdluli was building up to Mdluli. When you are faced with a matter like the case against Richard Mdluli, you don’t even have to think about it. You have to do it. Not even have to, you are going to. And you understand the consequences for him — and for you.

As a prosecutor you learn from the start that you have to be able to act independently. No one else can decide on cases or on courses of action for you. If you want to be any good you have to be independent. You decide on a course of action, and you stick to it. You have to be strong, and it takes a lot of self-confidence. You have to believe you are right. If you are going to prosecute someone, you are going to change their life. You can’t have doubts.

But, at the same time, you also have to have a lot of empathy. You learn a lot about human frailty when you spend a few decades in a court. When you are young you know nothing. You see the accused as a piece of meat. As your life skills improve, you begin to see them as a human being.

You understand what society demands and why that is important. As a prosecutor, you are trying to balance what society requires and what may or may not be the best thing for the accused. There’s not always a hell of a lot of room for play between “right” and “wrong”. If you let that line slide, you’re screwed.

Mdluli was the head of the police’s Crime Intelligence Unit for Gauteng. There had been some speculation about his lifestyle, about appointments he had made in the police service and crime intelligence. He was being investigated by two cops from the commercial branch of the police — because it was a Gauteng thing, they were from Cape Town.

The allegations were that he had used the informers’ fund of the Crime Intelligence Unit as a personal slush fund. In lay terms, he used the fund as his own bank account. He bought cars for himself and his wife and then used police money to upgrade to a better model.

And he had appointed family members, at high salaries.

Mdluli had also used and abused crime and intelligence structures to spy on people, to gather information to which he wasn’t entitled. And then there was the matter of an old murder charge, dating back to 1999, when Mdluli was a commander at the Vosloorus police station. He was suspected of murdering a man named Oupa Ramogibe. Ramogibe’s wife, Tshidi Buthelezi, had previously been Mdluli’s long-term girlfriend and the pair had a child together.

After Buthelezi and Ramogibe married in 1998, they had gone into hiding. It was alleged that, in early 1999, Mdluli and several of his junior officers tracked Ramogibe down and had him killed. The murder allegations against Mdluli had never really gone away — it just took a long time to find a captain willing to investigate properly. Although the case had never received much attention, the evidence was always there.

Mdluli, like everyone else, thinks I’ve got a vendetta against him. But there was a case for him to answer to: fraud, theft, corruption and, more importantly, murder. Oupa Ramogibe had a right to life. He had a wife, a family. If someone is going to live in South Africa, we can’t tell them what a wonderful Constitution we have but we can do nothing about the murder of your husband, your son, because it was on behalf of a very powerful policeman.

The murder case against Mdluli was circumstantial, which was much harder to prove but not impossible. The only reasonable inference from the evidence was that Mdluli had had Ramogibe killed. The probable killer, one of Mdluli’s accomplices, is now dead. Nobody else had anything to gain from Ramogibe’s death except Mdluli. I saw the murder docket, and I was offended by the fact that he had been able to duck and dive all that time. The murdered man’s family had not seen any justice.

So, there were these Cape Town cops. They were looking at issues with Mdluli’s cars, where the money had been taken from and where a deal had been made with police cars. Those same cops also took over the investigation of the murder case. I took more of an interest in the matter. I made sure the North Gauteng director of public prosecutions, Sibongile Mzinyathi, was up to speed on the case. He was satisfied. Then the matter was placed on the roll.

Cue the newly appointed Lawrence Mrwebi, who became head of the Specialised Commercial Crime Unit in November 2011. We got a letter from him, asking for an explanation setting out the charges against Mdluli. We received an instruction to provide a summary of the investigation, and to give the docket to Mrwebi. I advised the prosecutors not to hand over the docket, but to give Mrwebi the summary view.

I took the docket to Mzinyathi, who I was supposed to be reporting to, and who was an experienced prosecutor. I told him: “You read it and tell me.” Did he think there was a case? He said yes, there was. Now, in the hierarchy of the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) Mrwebi and Mzinyathi were equal in status. Mzinyathi and I were of the view that there was a case against Mdluli. Mzinyathi consulted the inspector general of intelligence and another representative from the ministry. They felt nothing in the case placed state security in danger and agreed that we should proceed.

Then Mrwebi issued an instruction that I should withdraw the matter. I made it clear that I would not. Mzinyathi, for all his faults, agreed with me. So I made an appointment to see Mrwebi.

When we arrived at the meeting, the first thing he said to us was: “Colleagues, I suppose you are here to test my powers.” It was clear that I was not going to back down and drop the charges. Mzinyathi explained that Mrwebi had not consulted either him or me, and that the NPA Act said he had to; the Act stated that Mzinyathi and Mrwebi had to concur about withdrawing the case, and they did not.

When it became clear to Mrwebi that he had no more room to manoeuvre, he admitted that he had already contacted Mdluli’s defence attorney and told him that we were dropping the charges. That, of course, changed things considerably. We were scheduled to go to court two days later. Either we had to proceed with the matter or withdraw. And the other attorney would have a letter on paper, from my boss, stating that the charges had been withdrawn.

The NPA was already in so much shit. We couldn’t air our dirty laundry in public. It is unbecoming. To save that situation, I agreed to withdraw the matter provisionally until we could sort out the impasse.

We got to court, and I withdrew to avoid an ugly scene. Then I sent a memo to the NPA’s deputy national director of public prosecutions, Nomgcobo Jiba. The 19-page memo set out the matter, the history, the facts, the merits, the chances of success and why I thought it should continue. “I am asking you to review the matter and to give an instruction to re-enroll,” I wrote to Jiba.

Then I added that if it was not re-enrolled I would take the matter on review.

I had absolutely no idea how I would do that, but a decision like that must be reviewable. It was not a threat, it was a promise to Mrwebi and Jiba: if you don’t reconsider Mrwebi’s decision, I will take you on review to the high court. Four days later I was told that I was being suspended, for made-up shit.

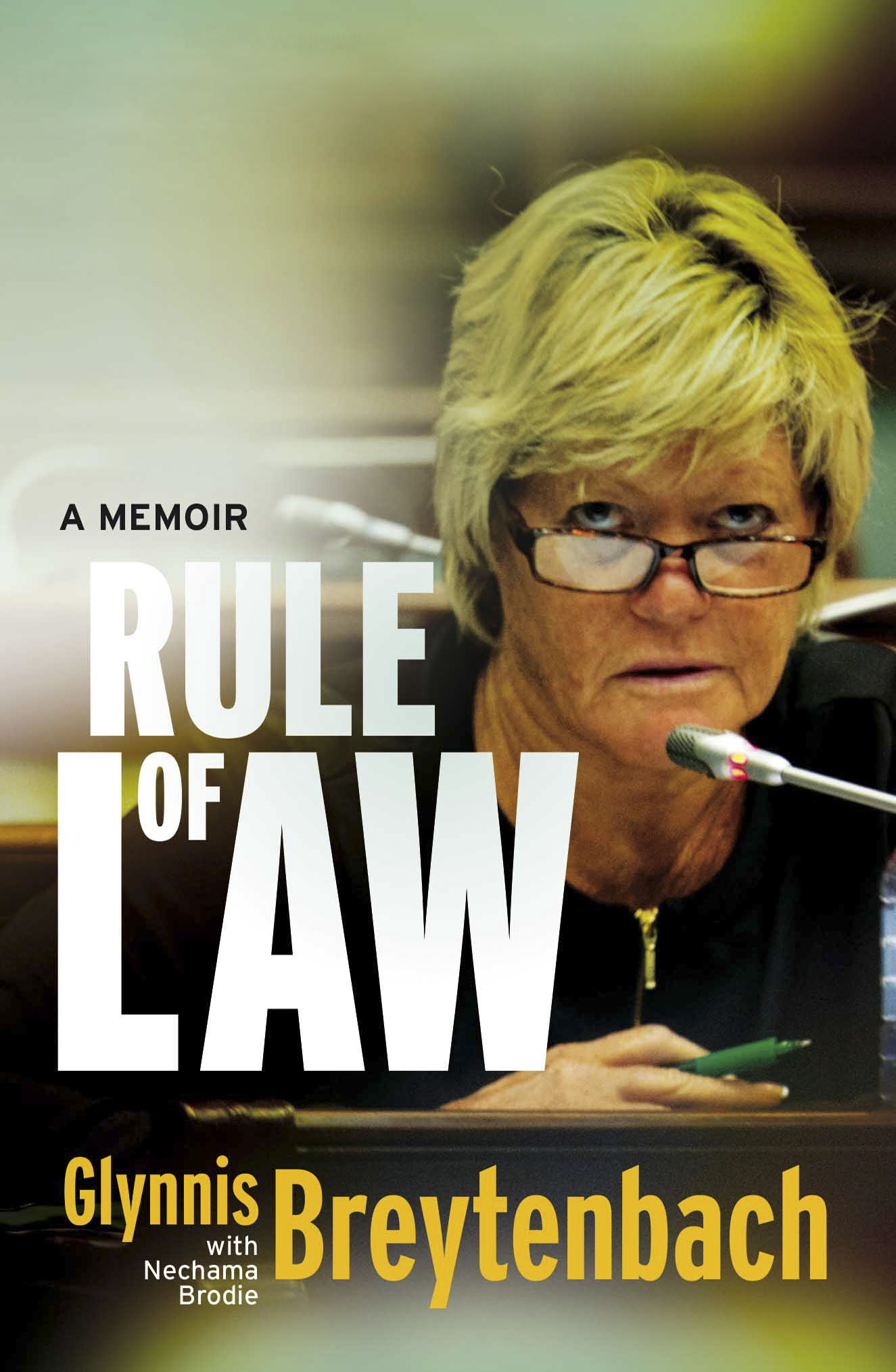

This an edited extract from Rule of Law: A Memoir, by Glynnis Breytenbach with Nechama Brodie, published by Macmillan. Breytenbach is now a Democratic Alliance MP. Brodie is a writer and editor