Keeping it real: Jessie Mabona preserves Ndebele culture and earns a livelihood by selling necklaces

Ngingumrazana weNdebele. At any traditional ceremony, I wear my Ndebele attire with pride — without knowing the significance of what I have adorned myself with. This disconnect has always bothered me but recent urges to be my best “Wakanda self” led me to do something about it.

Access to diaparo tsa setso, at an affordable price, has always been a taxi to Marabastad no matter whether I am looking for a seshoeshoe two-piece with an apron, seana-marena, the beaded skirt the kids wear on Heritage Day, xibelani — a skirt with many tiers — or the colourful striped umbhalo blanket the Ndebele are known for. There is a vendor under a tent or against a wall on every second corner of Marabastad, near Pretoria’s city centre, to cater to my needs.

The meaning of indigenous jewellery, clothing and sartorial expression has evolved over time, sometimes beyond recognition, or it is misrepresented. The original meanings and symbolism are no longer known.

Historically, indigenous clothing design was a deliberate act that annotated the existence of social structures and customs in the different indigenous groups. Take some of the Nguni women’s attire for example. An indigenously dressed Ndebele woman is characterised by her abundance of ornaments and jewellery that symbolises her status in society.

The most popular item in Matabele clothing is what I used to know simply as the umbhalo blanket, until my recent introduction to the term ikombese, from kombers, which is Afrikaans for blanket.

A bride will wear copper and brass rings, known as idzila, around her arms, legs and neck as a symbol of the bond she shares with her husband. There is also ijogolo, an apron shaped like a hand pointing downwards, which is given to a woman at the birth of her first child.

In the Zulu tradition, once a woman has given birth she wears a belt made of glass beads, cotton fabric and string, known as isibhamba, which acts as a corset. But that was then. Now anybody can wear this item.

“AmaNdebele ayadura,” a passer-by comments about one of the handmade beaded necklaces that costs more than R1 000.

It is just past midday on Jerusalema Street. Along the pedestrian pathway — past a fleet of Inyathi and Quantum taxis outside a shop that sells household items for cheap cheap — is Jezzie Beads’ Cultural Creations. This street stall has a wall, not more than two metres long, covered in Ndebele prints, two metal folding tables adorned with Ndebele jewellery and regalia and a small storage room where the owner, Gogo Jessie Mabona, keeps her merchandise.

[On display at Gogo Jessie Mabona’s stall in Marabastad (Oupa Nkosi/ M&G)]

In between chatting to fellow vendors and customers, Gogo Mabona and her apprentice busy themselves with thread, thin needles and multicoloured, almost microscopic, beads.

After leaving the motor industry where she worked in a factory, selling the colourful work of her hands in Marabastad for more than 40 years has been her only source of income. “This is how I make money. This brings in money. I have stock on display, stock in the storeroom behind us and stock at home. The stock is my livelihood,” she says, holding a string of black and white beads in her fist.

Women like Gogo Mabona, across the different indigenous groups, still have the skills to make diaparo tsa setso and the knowledge of the meaning behind each item but the messages held by indigenous clothing is lost in translation.

The director of the Durban Art Gallery, Mzuzile Mduduzi Xakaza, says this is because of changing fashions, social changes and changes brought about by migrant labour moving from the rural areas into the cities.

Xakaza says this in the foreword of the catalogue for an exhibition, titled Imfihlo Yobuhlalo, on at the Durban Art Gallery until April 29. This exhibition aims to celebrate the richness of Zulu culture as represented by beadwork the gallery has collected over a period of many years.

“Curators Anthea Martin and Hlengiwe Dube have crafted this exhibition to highlight the fact that traditional Zulu society has never been monolithic in terms of their usage of body adornment as a form of cultural expression,” says Xakaza.

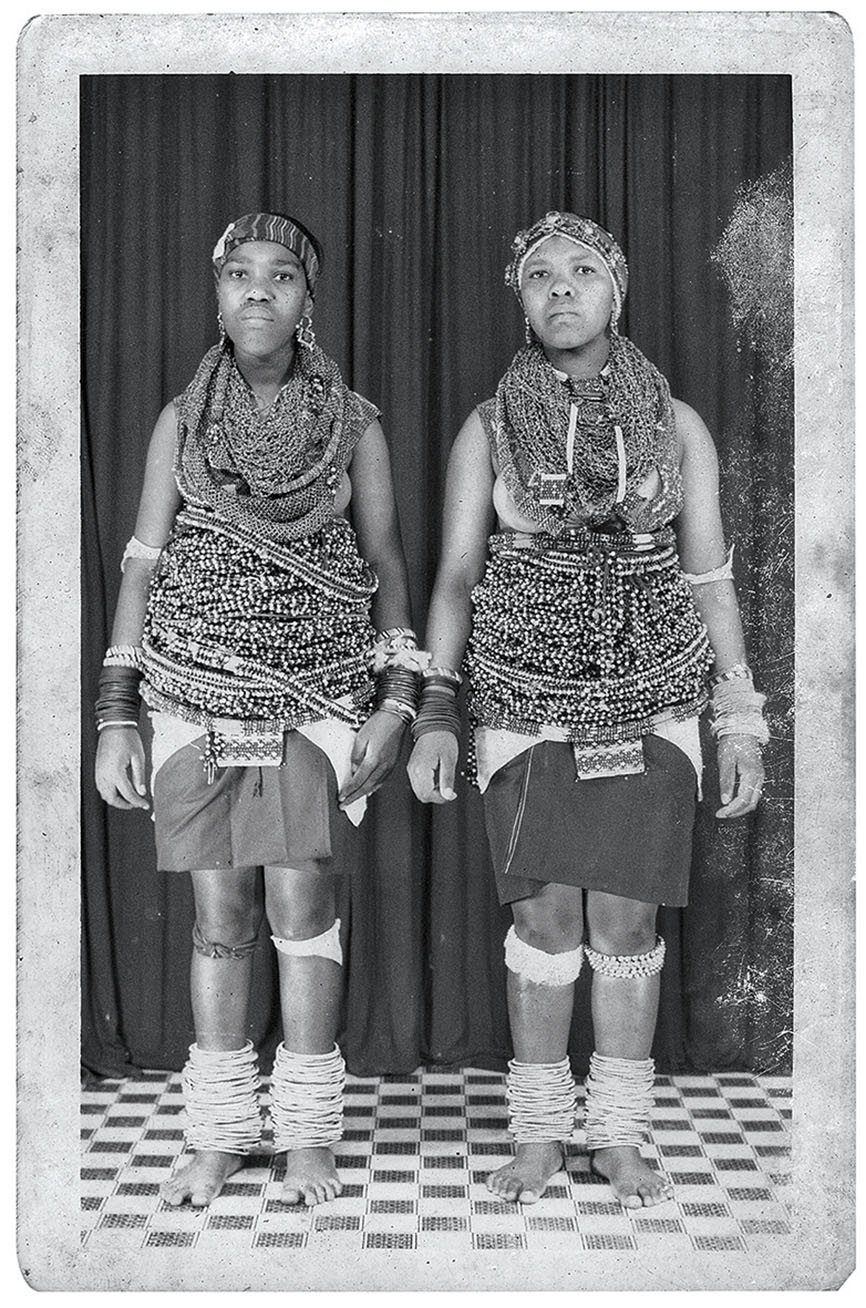

[The role that indigenous beadwork plays in identity and personal expression is also explored in an exhibition on at the Durban Art Gallery (courtesy of the Hlengiwe Dube Collection)]

More than 100 items have been selected from the gallery’s collection for their quality and as examples of beadwork from around KwaZulu-Natal. The catalogue documents each item, for which the Zulu and English name is given, with explanations of where and when it was made, as well as its function and the materials used.

Some people may be familiar with some of the artefacts on display, such as the necklaces, bracelets and headgear. But they will be introduced to items such as ingane, also called ishungu — beaded sweet tins that were popular among young people in the Drakensberg area. Young girls would carry the beautifully beaded tin full of sweets and money, which had been given to her by her relatives at the ukuphuma kwezintombi ceremony. These were held every two years.

A young man would carry the beaded tin full of sweets when he attended a special ceremony and also when he went to ukuyoshela. He would give the sweets to a girl he proposes to be in relationship with. The designs and the shapes change, depending on the area and when they were made.

The exhibition is not limited to the objects on display in the gallery. With sponsorship from the eThekwini municipality there is also an educational component that includes lectures and workshops, led by one of the curators, Hlengiwe Dube. Some of the topics covered range from the history of Zulu beadwork and understanding love-letter necklaces to traditional colour arrangements.

But is this enough? Will it reach people outside the white cube of a formal gallery? Is it not highly probable that we will celebrate indigenous beauties without understanding the depth of the history these carry?

The meaning of indigenous adornment will take the back seat while capitalism drives the narrative.

Vendors such as Gogo Mabona know the significance of traditional clothing and jewellery but economic survival has the first say.

“I’ll sell them to you. You want them, right? Money does not choose. If they want something and they have the money for it, you sell it to them,” she says.

But her hustle does not silence her fear of preservation being neglected.

“When we die, who will teach our children? They don’t want to know. When we die, our children will stay not knowing. Retailers stock things that I make and sell them. But they don’t know how they were made and they don’t know what they mean. They just sell them because they want business. I know the history. When I dress my customers, I tell them what each item means and who it is meant for.”

She shrugs with closed eyes and her hands folded against her chest.

After some time, in the stubbornly resilient tone Ndebele women are known for, she admits that she is yet to accept defeat.

Gogo Mabona is ready to teach the masses. “Ke teng! I’m available,” she says. All she requires is that interested people make themselves available at her stall for hands-on learning about beadwork, the significance of each item and her many stories of MaDdebele.

And she is not the only one. In every indigenous group there are wells of knowledge and all they need is an open mind from succeeding generations for them to pass the knowledge on to.

But I wonder about the necessity of this all. Are the messages that indigenous clothing carry being neglected because women are no longer bound by where they were located in the social structures of the indigenous groups?

Is this affecting me because a part of pop culture that I subscribe to is encouraging me to take pride in my blackness? With a shift in social norms, is there room for change in the messages that indigenous attire carries? Is the meaning behind the clothing still important or is the fact that we’re wearing it enough?