Statement threads at the Cape Town International Jazz Festival

The Cape Town International Jazz Festival has become a staple in the South African musical events diary. Defining jazz and what it means is a difficult enterprise because of the juxtapositions present in the genre. It was once considered the music of sin — of brothels and speakeasies. It is now more often referred to as a genre of expression, of freedom, of resistance and also of style.

Jazz is one of those genres, like hip-hop, that is a fusion of cultural expression that goes beyond sound. Jazz sounds like Sunday radio while Francophone English, Igbo and isiXhosa fly over your head. Like the voice of the late Eddie Zondi soothing you into the afternoon. It feels like three women tugging at your scalp with quick, attentive fingers weaving strands of hair down your back. But what does jazz look like?

Jazz made its way to South Africa in commercial recordings of American music, vinyls played on gramophones, moving picture films, and travelling American music troupes. South African jazz has a clear inspirational American link but the outcome was something unique to this country.

In our imaginings of jazz we think of a Sophiatown or District Six patched together from years of sensory revivals. There is always a sharply suited gangster draped in the latest European or American fashion. They wear a fedora cocked menacingly over their eyes, their shoes glistening. The shebeen queen, another staple, is clad in a skintight pencil dress reminiscent of the iconic Drum magazine cover of Miriam Makeba. A band in the corner dressed in crisp white shirts, bow ties, hats, their instruments slung across their chests worn like pendants. The air is heavy with smoke, brown beer bottles litter the tables. On the dance floors are brown bodies, black bodies, white bodies swaying. The dresses are cut loose, flare out at the bottom for easy movement. Heads covered in doeks, berets, poor-boy caps and trilbies.

We went to the Cape Town International Jazz Festival to explore the intersection of jazz and fashion at this contemporary African jazz festival.

For some artists their style is one that pays homage to a bygone era. Describing their aesthetic as ghetto African style, the three members of The Soil — Buhlebendalo Mda and brothers Luphindo and Ntsika Ngxanga — make nostalgic sighs and laughs at the mention of Sophiatown.

[Buhlebendalo Mda from The Soil has style that complements and reflects her music. (Dereck Green/Gallo)]

Mda has invaded the closets of Dorothy Masuka and Abigail Kubeka. She appreciates the ways vintage clothing reflects the era of a capella, allowing her mood to determine what threads she adorns herself in. For Ntsika Ngxanga, the fedora hat is a personal ode to the people who once populated Sophiatown, channelling their artistry and resurfacing the ripples of South African jazz in the global soundscape. It is retro, Luphindo Ngxanga smoothly recounts in his baritone voice. And what is more retro than a classic suit? Fitted in their Fabiani suits on stage, with Mda draped in velvet and a seshweshwe collar, their performance was enlightened by all the great saints: Nina Simone, Fela Kuti and Bra Hugh.

We felt uplifted experiencing jazz as a cultural exchange across the Atlantic, fluid and forever referencing those distant relatives. Seu Jorge’s performance on Friday night, just a man and his guitar, was a tribute to David Bowie. A congregation of Angolans and Mozambicans stage left sang praises and had chats with the Brazilian musician, who shared anecdotes in between enchanting ballads. The set included a nautical-themed stage and songs from the 2004 film The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou.

Whether you know Seu Jorge’s original music, or recognised the pastel-blue tracksuit and red beanie from a Wes Anderson flick, the Moses Molelekwa stage was lit up with the coming together of the Lusophone diaspora.

Of all the music festivals in the Mother City, the jazz fest feels like that other-worldly cousin. The one who visits for only a few days, speaks many languages, always brings home exotic treats and wears garments to make you wonder: “Could I pull that off?” Like festival-goer Vuyo Oyiya, with an Afro the size of Jupiter, snacking on Nik Naks with a curtain holder as a necklace. Or Afro-German Thabo Paul, visiting the homeland of his father, wearing a T-shirt accented in wax print.

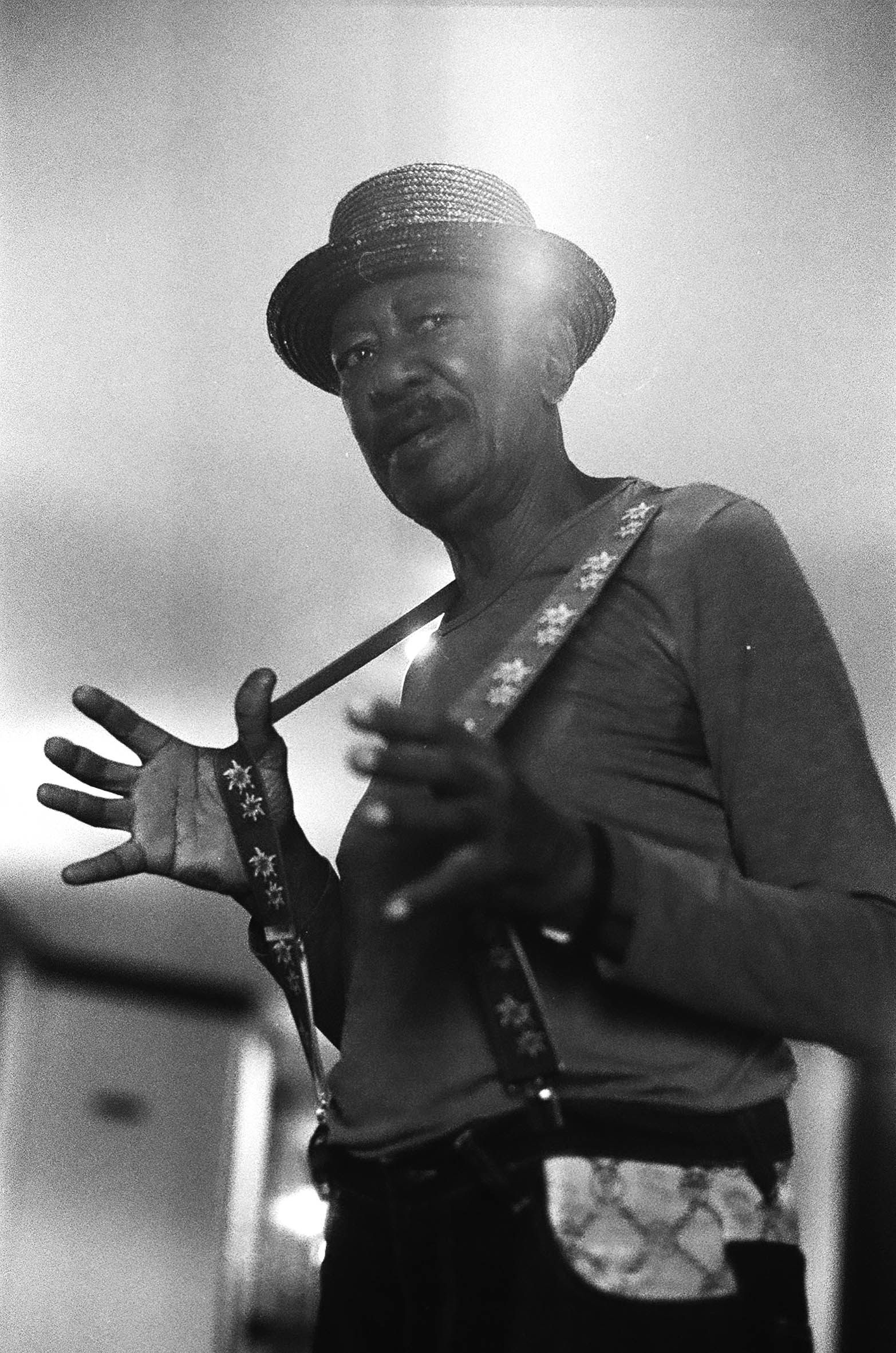

The intersection of fashion and jazz reveals to us that sharing of rhythms and materials, that process of exile in reverse. What photographer George Hallett documented in black-and-white film in the 1970s is resurging. To be in the presence of the legendary South African drummer Louis Moholo-Moholo was one of those moments of resurgence. Instead of a basic mic check one-two-one-two, Moholo-Moholo says in a low voice: “Yes baby, no baby, yes baby?”

His outfit is reminiscent of one-fourth of a barbershop quartet. A boater hat sits atop his head, a loose and silky black short-sleeved shirt printed with white music notes, nearby planets and yellow saxophones covers his torso.

The room in which Moholo-Moholo delivered a press conference felt the temperature drop and a vacuum of sound drew us in. It’s that feeling when an elder speaks and goes on a tangent. Every word a harsh reflection on life lived in exile, an indispensable contribution to the diasporic South African music genre.

[Vogue visions: Louis Moholo-Moholo dons his colourful suspenders and old-school boater hat (Chaze Matakala and Faye Kabali-Kagwa)]

“I like colours, you know, ’cause the music too is like colours. You’ve got black, you’ve got white, you’ve got no apartheid … It’s fantastic, this world of music … It’s the hidden force of this universe, in actual fact.”

While living in Europe, in between playing free gigs with big bands, Moholo-Moholo used to print shirts and caps with his name on them. “I would have been a designer if I didn’t play music,” he shares. “I pretend as if I’m rich, you know,” he says flexing his burgundy suspenders with white and yellow lilies, a serious smile on his face. “Rich people do that.”

How we dress goes beyond fashion and material wealth. For some artists their attire is a cultural expression. Here we can think of Amanda Black and her white Xhosa umchokozo that has become integral to her onstage persona.

[Amanda Black at The Cape Town International Jazz Festival (Derek Green)]

For award-winning pianist Nduduzo Makhathini, nothing he wears is an accident. “I really come from rituals and ceremonies of ngoma and all of that. That’s really where I draw my inspiration. I was initiated as a sangoma and when we go for our rituals it’s important to dress in a particular way. My interest has been trying to sort of repackage that and have some suggestions of that in what I wear. I love having African sort of prints somewhere ’cause I think that’s a big part of who we are,” says Makhathini.

A poor-boy cap covers his crown, a gold pennywhistle with a red tip is clutched to his chest, a wrist is adorned with white beads from his sangoma initiation.

The style of American singer and saxophonist Masego, on the other hand, is a compelling marriage of millennial cool and jazz but without the sophistication. His hair is an up-to-date variation of the 1980s high-top fade. Instead of a carefully cropped Afro his shaven sides give way to a pineapple sprig of hair at the top. He wears track pants, a striped white silk shirt, and slides. Around his neck he wears a thin gold chain, a tenor sax pendant with silver keys hanging from it. His style of music is termed trap house jazz, which is reflected in his dress sense and encapsulated perfectly in his pendant.

The pendant is representative of his own musical jazz journey. It is modelled after his own saxophone, which is affectionately named Sasha. The chain is symbolic of the musician’s relationship to hip-hop. Inspired by J. Cole’s track Chaining Day, Masego said the chain “represented a certain stage in a young man’s life where he becomes full rapper … It’s like the centrepiece of the whole thing. So I was like ‘Boom! In my chest. Right there!’”

On the Afro-futuristic spaceship came Blinky Bill, a Kenyan electronic music producer and artist, and Sibot, the Cape Town-based pioneer of electronic music in South Africa. Together they created an Afrofunk experience dressed in jumpsuits, black face masks and LED lights.

Blinky Bill, who sometimes jokingly refers to himself as a jumpsuit technician, wore one of his signature suits — a workman’s tie-dyed white jumpsuit that dissolves into navy from the waist down. On his face he wore a round black face mask with yellow triangles framing the side. Yellow markings highlighted the nose and the corners of the mouth. Sibot wore his signature face mask that transforms his eyes into large LED orbs.

Together the duo presented a strange comment on classism (in Blinky’s jumpsuit and Sibot’s pedestrian style of dress), African symbolism and cultural hybridity (in the form of masks) and technological advancement (with Sibot’s use of LED lights).

At the Cape Town International Jazz Festival jazz was a style icon never to be replicated but always respected. Jazz is built on circular patterned form structures that give way to endless improvisations and interpretations. The festival provided a stylistic interpretation of jazz as style from Afros, snapbacks, suspenders, jumpsuits and flashing lights and reminded us that jazz will forever be the home of cool.