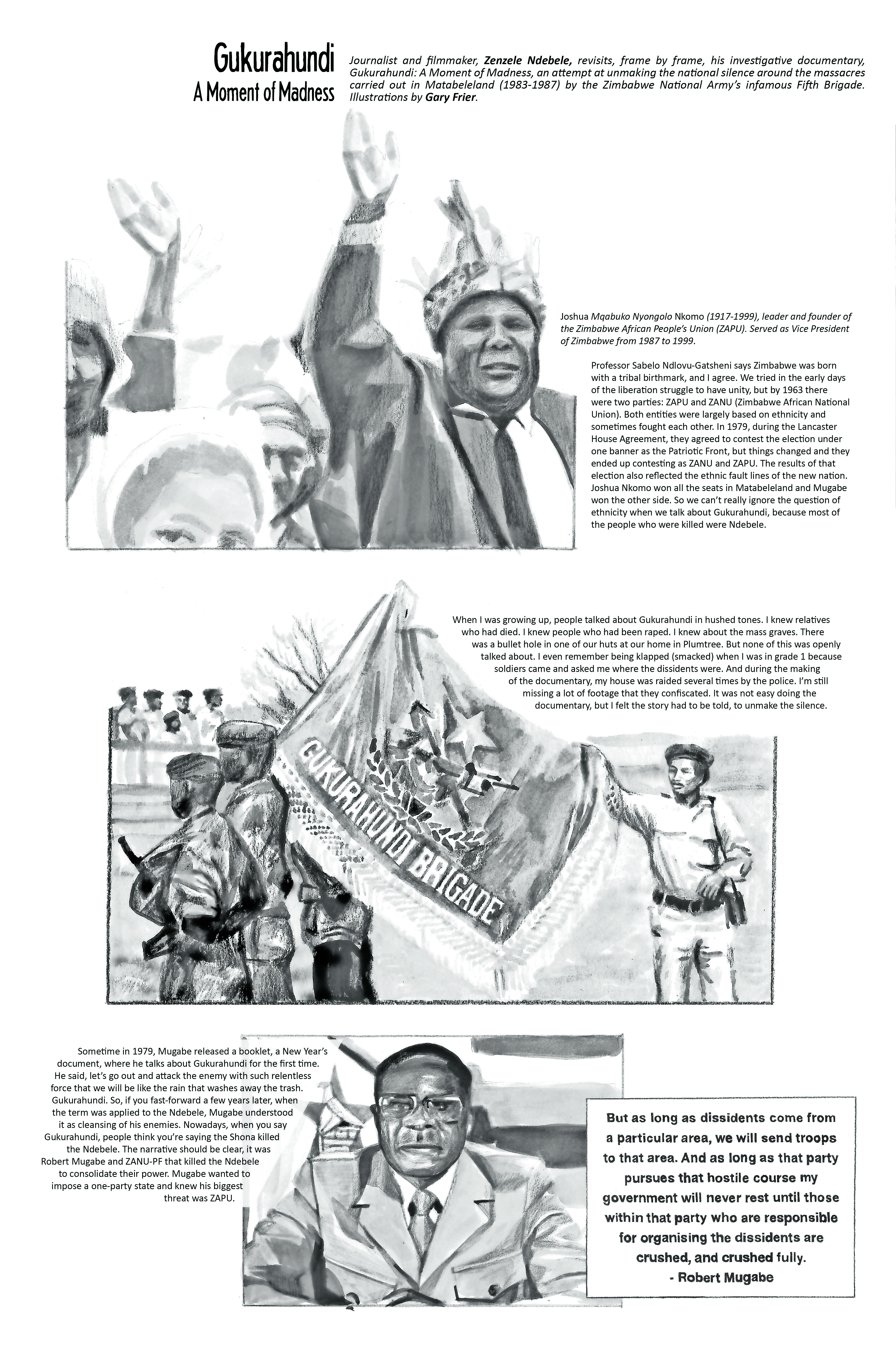

Heady moments: Robert Mugabe’s portrait

The invention of Zimbab-we is the theme of the new issue of the acclaimed culture magazine Chimurenga Chronic. Arising in part from the regime change in Harare in November last year, it is the publication’s most urgent offering yet in its Chronic phase.

The project was in incubation before the ousting of Robert Mugabe as president but was given impetus by the events that led to the installation of President Emmerson Dambudzo Mnangagwa, triggering

a short-lived sense of optimism in Zimbabwe.

As the title suggests, the seizure of the sceptre of power was also a catalyst for an outpouring of creativity, offering up a new country to the readers — a Zimbabwe being reshaped by its citizens, who hail from more than its political layer.

“I guess in a sense we also tapped into the energies that were there, because a lot of people really wanted to write about this moment,” says Bongani Kona, a senior editor with Chimurenga. “It was one of those moments that opened up a lot of writings and conversations and so much energy, so we just opened up a space to channel all of that.”

Participating in the collaborative editorial process, as well as writing two stories in the edition, Kona perhaps functions as the tone-setter, if one considers the effect of his initial salvo in the opening column pages titled “The way I see it: National Heroes Acre I”.

In it, there is a palpable struggle to articulate decades of pent-up emotions and the survivalist amnesia of the exile. Survivor’s guilt provides not so much a resolution as a gradual, daunting clarity. The events unfolding in Zimbabwe, not to mention the individual, abortive experiences of Zimbabweans he hears about as tragic news, combine to create a sense of vertigo. But he soon steadies himself.

“The regime has been invested in writing the contemporary moment and interpreting people’s lives,” he says. “I felt the extreme violence of that, even as I was growing up as a child, even when the opposition MDC [Movement for Democratic Change] was coming to the fore in the early 2000s. Everybody who supported the opposition was branded as a sellout. For me that violence has lived with me for a very long time and I really just wanted to write against that and open up about it. It’s something I feel completely angry about.”

His conversation with Brooklyn-based Zimbabwean choreographer Nora Chipaumire traverses similar terrain, but in more expansive tones. “She speaks like a very young person, but also has experience of the liberation war,” he says. “The people that speak about it tend to be quite old and they have these silences about things that they are unwilling to speak about. She was actually quite open and how that experience lives through her work.”

Fungai Machirori, a contributing editor in this edition, points out that the journal’s very name is a nod to the Zimbabwean liberation struggle, perhaps as a way of teasing out “all these different kinds of attachments” people have to the country. By suggesting unknown voices and troubleshooting blind spots only her relative proximity to the country can offer, Machirori was central in the effort to write Zimbabwe from within rather than in relation to its imposing neighbour South Africa.

Aided by its design ethos, the imagery and text in this edition offer up crisscrossing tangents, while maintaining an autonomy. Longtime contributing editor Stacy Hardy calls it “a fierce desire to place things in conversation and weave a bigger story out of the multiple threads”.

It is, she says, “fragmentation less as breaking than a coming together of multiple voices, big-band style”.

The fragmentation Hardy speaks of is the happy accident of functional design. In many instances, the bottom third of the pages are given over to page turns and continuations, whereas the upper two-thirds bring a rapid pacing, with a new story on every second page.

“In the age of digital journalism,” says Hardy, “the beauty of the newspaper is that you discover things by chance because they are in placement with each other. The visuals too; they are not so much supplementary, and more visuals in and of themselves.”

Two stark examples of this are to be found in “Home means nothing to me” and “Gukurahundi: A moment of madness”. The first is a map of Dambudzo Marechera’s “complicated relationship” with Harare and Zimbabwe, laid out as a collage one would make in a journal were it not for the corresponding, numbered vignettes that frame the outer edges of the double-page spread.

It is strangely emotive, perhaps because of its juxtaposition of black-and-white and spot colour, sparking the often subconscious effect of colour. The paradox of home and its wilful reframing rush forth with a heady clarity: Marechera seems to leap off the streets, only to be swallowed up again. The map is a collaboration between Tinashe Mushakavanhu, Nontsikelelo Mutiti and Simba Mafundikwa.

For designer Graeme Arendse, the etching of Chipaumire throughout her interview with Kona points to another running theme: liberation as expressed through the body.

The books section, titled “What African writers can learn from Cheikh Anta Diop”, skilfully fulfils what has become a galvanising modus operandi for Chimurenga: cartography as a way of redrafting reality. Diop’s intellectual concerns, the far-reaching tentacles of his research into Egyptology, his failures as well as the exploits of his intellectual rivals (such as Léopold Senghor) are portrayed in a series of seamlessly interweaving narratives that sculpt him into a living monument.

Reading the books supplement after trudging through the rest

of the issue, it seems that Diop, armed with a singularity of purpose that synergised his multiple disciplines, holds the master key to an invention of the self. He opens an intuitive portal, immune to the failings of nationhood.