Cameroons President Paul Biya, who has governed the country with an iron fist for 35 years, is seeking re-election in October, but there are fears the poll wont be fair. (Akintunde Akinleye/Reuters)

With elections just a few months away, the political situation in Cameroon looks bleak. There is the escalating conflict in the Anglophone region, there is the Boko Haram-linked instability in the north and then there is the president who is determined to extend his decades-long stay in power.

It is the Anglophone crisis that is currently making international headlines, although it has been brewing for several years.

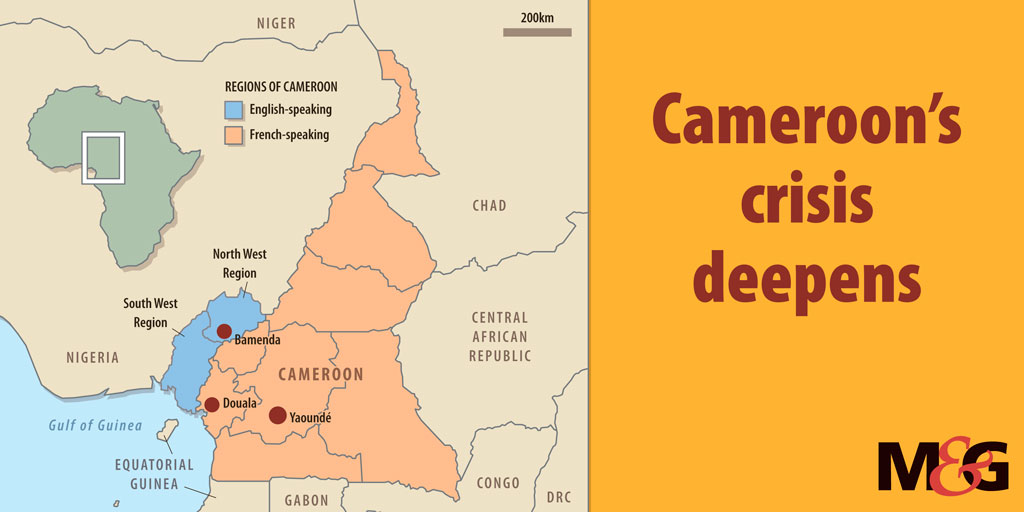

The conflict between state security forces and armed separatist groups appears to have intensified in recent weeks. The separatists believe that English-speakers in Cameroon — about 20% of the population of 24-million — have been marginalised and discriminated against by the predominantly Francophone government.

“If you see a civil war as a war between the government and its citizens, then I think it is headed towards a civil war, if it’s not a civil war yet,” Emmanuel Freudenthal, one of the few journalists to have reported from the affected region, told the Mail & Guardian.

Fighting on both sides has been characterised by extreme violence. A Human Rights Watch report released last month documented abuses by the separatist armed groups and the Cameroonian security forces. The report documents the separatists’ brutal enforcement of boycotts, particularly in schools, as well as the government’s excessive use of force against demonstrators, and instances of torture and extra-judicial killings.

The clashes have prompted many in the region to flee. The United Nations Office for the Co-ordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimates that more than 15 000 people have been displaced in the country since December last year, and that an additional 20 000 to 50 000 are seeking refuge across the border in Nigeria.

In addition, Cameroon is battling to contain a Boko Haram insurgency — another conflict characterised by extreme violence. Last month, a video emerged that showed Cameroonian soldiers executing two women and their children in the country’s far north, on suspicion of supporting Boko Haram. The video is representative of the military’s heavy-handed approach to dealing with tensions in the north and the Anglophone regions, say activists.

What does all this mean for the election? President Paul Biya has governed Cameroon for 35 years, and plans to run again in the October 7 poll — even though he is, infamously, an absentee president, spending up to a third of his time out of the country, usually in a luxury hotel in Switzerland.

“It’s going to be quite hard to organise voting in the Anglophone regions. It’s already hard to organise voting in the extreme north,” said Freudenthal. “That means a whole section of the population is not going to be able to vote.”

Things are probably going to get worse, he added. “The government’s military strategy has been to increase violence and increase military attacks against both armed groups and the civilian population…I can’t predict what the armed groups are going to do but it seems most likely they are going to ramp up their activities to make a point.”

‘Ghost towns’

The separatist movement is hard to pin down, given its fractured nature. Though the protests in 2016 were led by lawyers and teachers, with a decidedly non-violent bent, the government’s harsh reaction has strengthened the hand of hardliners and armed factions. They want to secede from Cameroon proper and form a new state called Ambazonia — although even among the hardliners there are a variety of actors who want slightly different things, and with different opinions on how to achieve them.

Though there is a group of activists who describe themselves as an “interim government in exile,” the extent to which this group is considered legitimate by a plurality of Anglophone Cameroonians is unclear. Human Rights Watch estimates that there are between five and 20 armed factions.

The sheer number of armed groups may complicate any attempt to broker a ceasefire or peace agreement — not that any such attempt has yet been made. In fact, the violence is getting worse.

According to Jeffrey Smith, head of Vanguard Africa, an advocacy group: “Since August 2016 especially, the acts of violence [by the armed groups] have become more routine and more brazen…at this point, it almost seems as if armed groups and government forces are actively bidding to outdo one another in terms of shock value.”

For example, in late July, a police officer was decapitated by suspected separatists.

In addition to brutal attacks on the Cameroonian government, the separatist movements are also responsible for the enforcement of “ghost town”days — mass boycotts of work and schools. Those who violate the boycotts are often subjected to brutal retaliation, forcing compliance with the armed separatists’ agenda.

As Max Bone, an expatriate development worker based in Buea, one of the Anglophone region’s major cities, described on social media: “The ghost town has yet to officially start in Buea, but the gunshots have. Around 30 [minutes] of back and [forth] shooting between the non-state armed groups and the military took place just now. Everyone is urging one another to sleep on the floor tonight to be safe.”

Activists say that the ghost days are intended as a form of economic sabotage. They serve other purposes too: as an information-gathering tool for the separatists, and to help telegraph the strength of the movement to the Cameroonian government.

A case in point: the July 23 ghost-town day in Buea, where the boycott was successfully implemented despite being forbidden by the mayor, simultaneously highlighted the strength of the separatists and the weakness of the government.

It is not yet clear how the separatists will use their strength in the upcoming election, which roughly coincides with the second anniversary of the declaration of an independent Ambazonia. They could throw their support behind the opposition party candidate, Joshua Osih Nabangi, running on the Social Democratic Front ticket,or they could boycott the vote. Reports from Buea claim that separatist groups there have beaten people carrying voting cards, declaring them to be the enemy.

“When they claim that simply possessing a voter card makes you an enemy, it gives a disturbing sign as to what their values actually are,” said one aid worker working in the region, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons.

Government weakness

As evidenced by the failure to put an end to ghost days, the Cameroonian government’s ability to project its authority into Anglophone regions is limited. Perhaps because of this, the government’s response to the crisis has been heavy-handed. Human Rights Watch has documented a number of testimonies concerning the government firing live ammunition into crowds of demonstrators.

Videos have emerged from the region, some purportedly showing families being massacred, others detailing the experience of a woman who claims to have been raped in government custody, and others documenting beatings and humiliation. Though the Cameroonian government has promised an investigation into the video of the execution in the country’s far north, so far the government has not publicly disciplined the security sector officials accused of misconduct in Anglophone regions. Furthermore, the Biya administration has targeted Anglophone activists in a series of arrests of high-profile activists and an internet blackout that lasted 93 consecutive days.

Biya himself presents a hurdle to the prospect of a swift and peaceful resolution of the grievances of Anglophone Cameroonians. His reputation for authoritarian repression and his persistent marginalisation of the Anglophones makes the prospect for an inclusive, peace-oriented dialogue seem dim.

Given the Biya administration’s posture towards the separatist movement — as well as its attitude towards democratic norms of accountability — and the number of armed groups that may serve as spoilers to any peace process, there is a need for external pressure to bring all the parties to the table for an inclusive dialogue. This might be a problem that Cameroon cannot solve on its own.

But if the regional and international community is going to make any difference before the presidential vote, they are going to have to act soon. Ensuring that Cameroon’s elections are free, fair, peaceful and credible — and thereby ensuring that all Cameroonians get to exercise their democratic right — demands action today.

“I am especially concerned about the blatant, increasingly complex forms of human rights abuses going on in the country for the last 18 months or more. The trends are particularly alarming,” said Kathleen Ndongmo, an entrepreneur and human rights activist.

“There is very little action from regional bodies and the international community which is extremely disturbing … It’s about time coalitions of civil society at home, in the region and globally begin to find ways to let this government know that we will not stand by and watch them continue to violate a people with impunity without consequence. If the government of Cameroon will not stop oppressing the people of Cameroon, then they should be ready to face serious consequences, one of which can be sanctions against government officials directly.” — Additional reporting by Simon Allison